Friday, December 24, 2021 – How about a Crystal Palace in Midtown?

THE RIHS KIOSK IS OPEN TODAY FROM 11:30 A.M. TO 4:30 P.M. TODAY, DEC. 24 FOR LAST MINUTE SHOPPING. SUPPORT THE R.I.H.S. BY PURCHASING YOUR GIFTS AT THE KIOSK.

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 24, 2021

“New York Wonders

I’m Sorry I Missed”

Stephen Blank

The 554th Edition

Many engineering achievements are stars in our City’s history. The old Croton aqueduct was an engineering marvel that made the City safe and also created the foundation for its growth. The Brooklyn Bridge was an amazing feat and so were our skyscrapers that pushed higher and higher. But other engineering exploits have been long forgotten. So, let’s take a brief tour of a couple of these lost wonders.

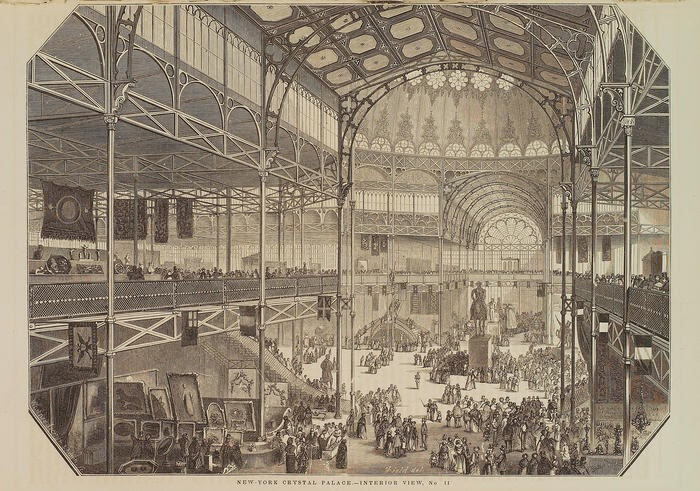

New York Crystal Palace

The New York Crystal Palace was a dome-topped glass structure that took up nearly an entire square block. It was constructed for the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations in New York City in 1853, on a site behind the Croton Reservoir, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues on 42nd Street, in today’s Bryant Park. The Crystal Palace was the centerpiece of this first World’s Fair hosted by the United States.

| Designed by architects Georg J. B. Carstensen and Charles Gildermeister, the Crystal Palace was inspired by the Crystal Palace built in London’s Hyde Park for the Great Exhibition of 1851. At the time, the New York Crystal Palace was the largest building in the western hemisphere. The massive scale, expansive walls of glass, and beautifully ornate wrought iron details of the building brought visitors from everywhere Visitors to the fair saw the era’s most technologically advanced innovations. One invention that debuted at the fair was Elisha Otis’s elevator. Another attraction that drew visitors to the Exhibition was the Crystal Palace’s neighbor, the Latting Observatory. At more than 300 feet tall, it was the tallest manmade perch on the continent at the time. Sadly, the Crystal Palace would not survive much longer than the Exhibition. After the fair closed in November 1854, the building was leased as a special events space. It became the new home of the Fair of the American Institute, an event similar to the World’s Fair but smaller. Just four years later, in October 1858, a raging fire destroyed the gleaming Palace. London had its Crystal Palace, and so did we. And San Francisco had (still has) its cable car system. And so did we. |

| New York Cable Car System While horse-cars remained in operation until 1917, their network was gradually converted to cable car operation after the Civil War. Cable cars were invented in 1873 by Andrew Hallidie to climb the hills of San Francisco. They relied on an underground cable that was pulled by a remote steam-powered engine – later electric – that moved at a constant speed, with cable car operators able to either engage or disengage from the system in order to move forward or come to a stop. |

Third Avenue Railway System cable car, c. 1885, public domain archival image

The very first New York cable car was actually a steam driven device to help rail cars cross the new Brooklyn Bridge. The Third Avenue Railroad, a horsecar operator since 1858, built the first street-running cable line from Manhattan to Harlem, on 125th Street. Apparently, in entrepreneurial New York City, there were several different cable operations, most tangled in lawsuits over Hallidie’s patent infringement. A gorgeous power station for one of these lines still stands at the corner of Houston and Broadway – the Cable Building designed by McKim, Mead & White for the Metropolitan Traction Company.

When it became operational in 1893, a fleet of 125 cars served 100,000 passengers from Bowling Green to 36th Street each day. Today, the Angelika Film Center occupies the basement space which formerly housed the cable powerhouse.

In 1883, the big idea was to build a system of 29 lines of three major uptown cable lines running on embankments. But it all came to an end around 1909 when all trollies had converted to electricity.

Paris had its pneumatic mail system. And so did we.

New York Pneumatic Mail

Beginning in 1897, New York City’s Post Office Department moved a large portion of its mail underground, through miles of pneumatic tubes installed under the city, connecting the major postal stations. Letters were packed into metallic canisters and swooshed throughout the city. In 1913, the postmaster installed new, 24-inch-wide tubes between the Grand Central and Pennsylvania Terminals, which were built large enough to carry 100-pound bags of mail.

Terminals of the Tube Receiving and Sending Apparatus in the Sub-Postoffice

The Manhattan installation was constructed by the Tubular Dispatch Company which was purchased by the New York Pneumatic Service Company, which continued to operate the tubes under contract to the postal service. Construction after 1902, starting with the line between the New York and the Brooklyn general post offices, was completed by the New York Mail and Newspaper Transportation Company, all owned entirely by the American Pneumatic Service Company.

Eventually the network stretched up both sides of Manhattan all the way to Manhattanville and East Harlem, forming a loop running a few feet below street level. Travel time from the General Post Office to Harlem was 20 minutes. A crosstown line connected the two parallel lines between the new General Post office on the West Side and Grand Central and took four minutes for mail to traverse. Using the Brooklyn Bridge, a spur line also ran from lower Manhattan, to the general post office in Brooklyn, taking four minutes. Perhaps best of all, operators of the system were called “Rocketeers”.

Image Credit: Library of Congress via Flickr // No known copyright restrictions

At its peak, the tubes transported almost 100,000 letters daily—about 30% of the city’s mail. But I don’t think our pneumatic system ever rivaled the romanticism of the Parisian “petit bleu”. In François Truffaut’s 1968 movie Baisers Volés (Stolen Kisses), we can follow the physical journey of the protagonist’s heartbreak around the city, after he poignantly posts a farewell love letter in the slot marked ‘PNEUMATIQUES’ and bids it adieu.

When we entered World War I, the high cost of operating the tubes was seen as too expensive, since funds were needed for the war effort. The underground delivery system ended permanently in 1953.

Remarkable memories in our City’s history. Thanks for taking the trip with me.

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND ANSWER TO ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

It’s the Holland Tunnel ventilation shaft/building, this one on the New Jersey side. And thank you for the interesting article on the Houston Hall buildings. I work a block away, at Hudson Street (I am in the office half of the time these days, remote the other half). I’ve never had occasion to go to Houston Hall though.

Andy Sparberg, our transportation guru got it right, too!!

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Stephen Blank

RIHS

December 18, 2021

Sources

http://www.cable-car-guy.com/html/ccnynj.html#tarr

https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/2010/07/cable-cars-trolleys-and-monorails.html

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment