Tuesday, January 11, 2022 – Trash has always been a problem and almost sunk the city

TUESDAY, JANUARY 11, 2022

ISSUE #569

The Legend of

New York City Garbage

Stephen Blank

When we came here so many years ago, AVAC, the Island’s new, modern trash removal system was one of our Island’s major attractions. Wooshing away garbage underfoot, we didn’t need large trash rooms or to worry about vermin. Well, with AVAC blocked for us at any rate, my thoughts turn to trash in the City.

Always a problem, but at first nothing was done: New Amsterdamers chucked rubbish, filth, ashes, dead animals and such stuff into the streets. In 1657, the city banned citizens from tossing “tubs of odor and nastiness” into the streets but with little impact. Only in 1702 would semi-organized street cleaning begin. Citizens piled stuff in front of their homes each Friday to be collected by Saturday night scavengers. Rubbish-pickers took what they could and sold it to bone-boiling plants; the rest was left to hogs, and then to rot. Many folks gleaned among the refuse.

A tenement gleaner, New York City (1900-1937). Lewis Wickes Hines. NYPL

Only in 1881, the New York City created a Department of Street Cleaning in response to the public uproar over litter-lined streets and disorganized garbage collection. In 1929, it became the Department of Sanitation.

In the course of the next century and a half, the amount of city waste grew enormously (by early 21st century, nearly 50,000 tons of waste and recyclables were collected in New York City each day), and the character of trash changed as well (with autos, no more horse manure, urine or dead horses; now huge amounts of concrete and plastic). But the big issues remained the same: collecting it and then getting rid of it.

In its early days, the Department of Street Cleaning didn’t function at all. People were knee-deep in street muck, horse urine and manure, dead animals, food waste, and broken stuff. The problem was that people in charge of street cleaning were in the pockets of people like Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall. Other cities all over the world had figured out how to solve this waste problem decades earlier, but New York persisted in being infamously, disgustingly dirty.

In New York at the end of the 19th century, it was not uncommon for dead animals to lie on the streets for weeks

A tenement gleaner, New York City (1900-1937). Lewis Wickes Hines. NYPL

Only in 1881, the New York City created a Department of Street Cleaning in response to the public uproar over litter-lined streets and disorganized garbage collection. In 1929, it became the Department of Sanitation.

In the course of the next century and a half, the amount of city waste grew enormously (by early 21st century, nearly 50,000 tons of waste and recyclables were collected in New York City each day), and the character of trash changed as well (with autos, no more horse manure, urine or dead horses; now huge amounts of concrete and plastic). But the big issues remained the same: collecting it and then getting rid of it.

In its early days, the Department of Street Cleaning didn’t function at all. People were knee-deep in street muck, horse urine and manure, dead animals, food waste, and broken stuff. The problem was that people in charge of street cleaning were in the pockets of people like Boss Tweed and Tammany Hall. Other cities all over the world had figured out how to solve this waste problem decades earlier, but New York persisted in being infamously, disgustingly dirty.

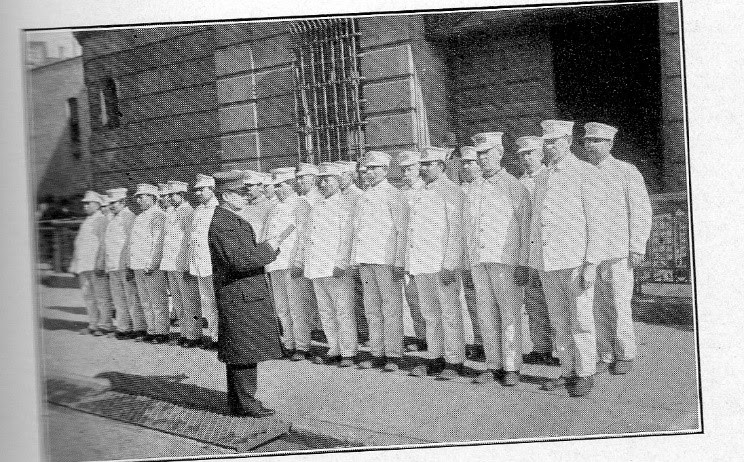

Tammany regained power in the next election and Waring lost his job. Still, even though in office for only three years, many of Waring’s innovations remained. After he left, nobody could use the old excuses that Tammany had used to dodge the issue of waste management – that the city was too crowded, with too many diverse kinds of people, and never mind that London and Paris and Philadelphia and Boston cleaned their streets. New York was different and it just couldn’t be done. Waring proved them wrong. Rates of preventable disease went down. Mortality rates went down. It also had a ripple effect across all different areas of the city.

Before and after photos of street corners in New York in 1893 and then in 1895 taken for Harper’s Weekly reveal the change that took place when the system finally began to work. New York Public Library

From this point on, New York had a method of trash collection. The issue of what to do with the trash that was collected remained, however.

New York’s main modes of disposal, into the eighteen-nineties, were rendering plants, hog feeding, fill operations, and ocean dumping. What little recycling there was came from private scow trimmers who loaded the garbage barges along the city’s shoreline. Rights for sifting through the trash were bid out to labor bosses who paid the city nearly $90,000 in 1894 for this privilege. They sorted out iron at $4.50 per ton, zinc at $1.75 per 100 pounds, paper at 25 to 40 cents per 100 pounds, along with commodities such as bones, fat, hemp twine, and old shoes.

Waring had novel ideas about what to do with what his White Wings collected. In 1895, he instituted a waste management plan that eliminated ocean dumping and mandated recycling. Household waste was separated into three categories: food waste, which was steamed and compressed to eventually produce grease (for soap products) and fertilizer; rubbish, from which paper and other marketable materials were salvaged; and ash, which along with the nonsalable rubbish was landfilled. Now, by keeping the sortable rubbish separate from the ashes and food waste, Waring hoped to capture the recycling value for his department’s budget.

The vast quantity of coal ashes became a significant source of landfill as the city’s islands expanded their shorelines. Rikers Island was enlarged from 80 acres to 400 acres. Recycled ash was also incorporated into cement cinder blocks. The wet garbage was sent to pig farmers in Secaucus, N.J., or to a composting plan in Jamaica Bay that extracted oil and made fertilizer. Meanwhile, his suggestion that rubbish should be incinerated rather than dumped at seas was much appreciated by the shoreline inhabitants of New Jersey and Long Island – though ocean dumping resumed during World War I and never really ended until the 1930s.

In 1919, Mayor John Hylan proposed that a fleet of incinerators be placed throughout the boroughs. When a judge ruled, in 1931, that New York City would need to end its ocean dumping—New Jersey had successfully sued the city over the trash blanketing its beaches—incineration became even more attractive. But incinerators were expensive to repair and maintain, and the pollution they produced was particularly unpopular. Moreover, increasing amounts of new materials – aluminum, plastics – made incineration more difficult. Burying the waste seemed a better idea. In the 1930s, Robert Moses launched an ambitious program to build both incinerators and landfills. At one point, there was a network of some 89 incinerators and landfills all over the city.

Inwood’s 215th Street Incinerator – January 29, 1937

After the 1960’s, no new waste disposal facilities were constructed in the city. Active incinerators numbered eleven in 1964, seven in 1972, three in 1990, and zero in 1994. Six landfills, filled to capacity, were closed between 1965 and 1991, leaving the City with only one remaining landfill — Fresh Kills on Staten Island, which after mounting protests by Staten Islanders, was finally closed in 2001 (though reopened on September 12, 2001 to receive the wreckage of the World Trade Center).

With the city’s last landfill closed, then mayor Rudy Giuliani’s solution was to increase the privatization and export of trash. By 1995, New York State was the largest exporter of waste in the country, sending it predominantly to Pennsylvania, as well as eleven other states. This is still the basic arrangement today.

Note that waste collection had become divided between public and private organizations. The public system handles waste from residences and government buildings as well as some non-profits. This “public waste,” which accounts for about a quarter of the city’s total, is collected by New York’s Department of Sanitation, which has become the largest waste management agency in the world with a yearly budget greater than the annual budget of some countries. The other three-quarters of New York’s garbage is generated by commercial businesses, mostly debris from construction projects. Collection of this “private waste” does not come out of the city’s budget. Instead, business must pay one of the City’s licensed waste haulers to take it away.

There’s more to the story of course – recycling would take another essay at least and the story of exporting our waste is scarcely over. But for now, it’s time to take out the garbage. Thanks for your time.

Note, I gleaned extensively from Robin Nagle (Picking Up) and Martin Melosi (Fresh Kills: A History of Consuming and Discarding in New York City) from several of the sources below.

Stephen Blank

RIHS

January 5, 2022

Tuesday Photo of the Day

SEND YOU RESPONSE TO ROOSEVELISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

IF BOUNCED-BACK SEND TO JBIRD134@AOL.COM

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

The bell was cast from coins donated by delegates of 60 Nations at the 13th General Conference of the United Nations Associations held in Paris in 1951, and from individual contributions of various kinds of metal. It is housed in a typically Japanese structure like a shinto shrine, made of cypress wood.

At the presentation of the bell, Mr. Renzo Sawada, Japanese observer to the United Nations stated that the bell: embodies the aspiration for peace not only of the Japanese but of the peoples of the entire world. Thus it symbolizes the universality of the United Nations.Location (Building): Exterior Ground

Donor Country: Japan

Artist or Maker: The Tada Factory

Exterior Ground Floor: Rose Garden

Dimensions: Height: 39 in.; Diameter: 24 in.

Donation Date: June 8, 1954

Jay Jacobson and Laura Hussey got it right!

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

STEPHEN BLANK

Sources

https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/the-history-of-new-york-told-through-its-trash

https://sustainability.weill.cornell.edu/recycling/brief-history-new-york-city-recycling

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/oct/27/new-york-rubbish-all-that-trash-city-waste-in-numbers

http://scrapyardexhibit.org/the-colonel-who-cleaned-up-new-york/

http://scrapyardexhibit.org/the-colonel-who-cleaned-up-new-york/

https://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/when-new-yorkers-lived-knee-deep-in-trash/ https://www.newyorkalmanack.com/2021/01/george-warings-men-in-white/[Top photo: The Folding Chair; second photo: Bettman/Corbis; third photo: Postcards From Old New York/Facebook; fourth photo: Alice Austen; fifth photo: The Folding Chair]

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment