Wednesday, March 2, 2022 – THE WATER TOWER STORY CONTINUES

WEDNESDAY, MARCH 2, 2022

611th Issue

THE HIGHBRIDGE

WATER TOWER

PART 2

FROM UNTAPPED NEW YORK

JEFF REUBEN

The Technologist, September 1870. Public domain

To correct the record, the designers should be identified as Craven, Dearborn, and their colleagues. Given the Water Tower’s distinctive architectural character, it is possible that some uncredited architect also played a role.

“Review of the Design of the Collective System of the High Service Water Works at Carmansville, New York City,” by L.L. Buck, 1868 (Collection of the author.)

Although construction on the Water Tower did not begin until the summer of 1869, its design was completed by the spring of 1868.

We know this thanks to a thesis written at that time by Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute student L.L. Buck. It provides dimensions that are consistent with those in Dearborn’s early 1870s plans and its narrative descriptions and calculations are much more detailed than those in news articles or official reports. Who said schoolwork isn’t important?

Among other things, the paper tells us that in the Tower’s interior there “will be a brick lining 8 inches thick and with an air space, between it and the stones of the wall, of 4 inches” and the stairs “are to be of iron, cast treads and wrought frame work in each story to wind from one side around to the opposite side, or occupying 8 sides, the landing on each floor to be vertically over that of the preceding.”

Incidentally, the student, whose full name was Leffert Lefferts Buck, went on to an accomplished career including serving as Chief Engineer on the Williamsburg Bridge.

It Not Only Resembles a Medieval Tower, It Is Built Like One Too

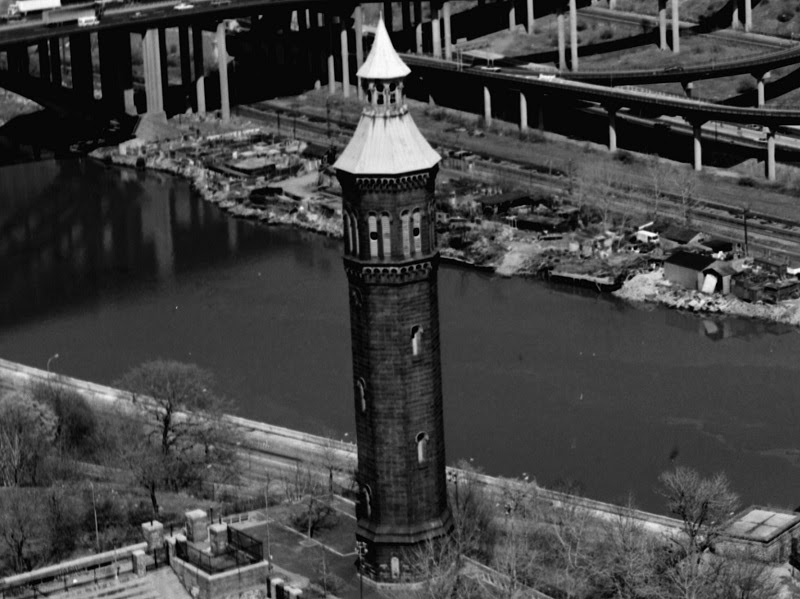

Although built for a functional purpose, the Highbridge Water Tower is an ornamental building often likened to medieval minarets and campaniles (Italian bell towers) and the comparisons have considerable merit, both stylistically and structurally. The architectural connections are obvious, but the physical similarity is not as readily apparent until one ventures inside or looks at architectural drawings.

Built more than a decade before the first steel frame skyscrapers of the 1880s, the Water Tower has load bearing walls designed to support the weight of the building above, including a full water tank. Much like a historic church, it has thick walls at the bottom and thinner ones at upper levels.

Transition from shaft to tank room (now observation level)

Both Buck’s paper and Dearborn’s plans show that at the base the octagonal structure has an outer diameter of 29 feet and walls 5.5 feet thick, leaving only 18 feet inside. Above the base, the main shaft tapers slightly so that the walls are 4 feet thick but the interior space remains 18 feet across. The few windows in the base and shaft are narrow and vertical to maintain the structural integrity.

Exterior of the tank room, now observation level

In contrast, the walls of the tank room, which is now the observation level, only support the weight of the cupola above. They are a much slimmer 1 feet, 4 inches thick and have expansive windows, two on each of the eight sides. As a result, this part of the tower has a more spacious, light-filled interior of 25 feet, 8 inches in diameter.

Its Builder Was a Crony of Boss Tweed

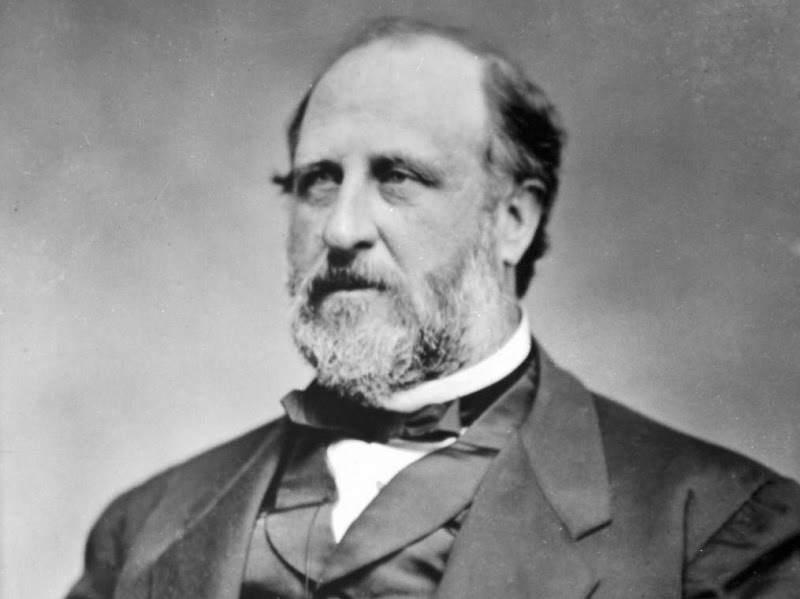

William M. Tweed (1870)., viaWikimedia Commons

A silver-plated model of the Highbridge Water Tower, now owned by the New-York Historical Society, bears a lengthy inscription stating that it was presented to John L. Brown, the building contractor, “by the Employees on the Tower Works, as a Souvenir of the pleasant times passed in his employ.” It also lists various City officials, among them William M. Tweed, Commissioner of Public Works. In fact the linkage between the two was more than incidental.

Brown, who the New York Times once referred to as “the Tammany street-cleaner and contractor,” told an investigatory commission in 1872 “I had no connection with Mr. Tweed.” However, “Boss” Tweed acknowledged in 1877 what many long suspected; he held a secret interest in Brown’s street cleaning company and ensured that it received city contracts and payment for work it did not perform. In jail by then, he made confessions like this in an unsuccessful effort to be paroled. As for Brown, he was off the hook, having died a rich man two years earlier.

As for the Water Tower, Brown received that contract in 1867 from the Croton Aqueduct Board, which had autonomy from Tweed and other politicians. However, Tweed, who was infamous for inflating costs on innumerable public works projects to benefit himself and his cronies, most notoriously with the “Tweed Courthouse,” gained control of Croton Aqueduct operations in April 1870 while the Tower was under construction. There is some evidence that similar corrupt practices occurred on a modest scale with the Tower. As for that silver model, it seems more likely a gift from Tweed, known for his affection for luxuries, than from workers paid modest wages.

Robert Moses, viaWikimedia Commons

The Tower’s water system operations ended on December 15, 1949 when it was made obsolete by a new electric powered pumping station at 179th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. The City’s Department of Water Supply, Gas, and Electricity planned to raze the old structure, which had become a target of vandals.

In stepped Robert Moses to the rescue. Yes, really. As the New York Herald Tribune reported in 1951, “the Parks Department said it was the intention of Commissioner Robert Moses to save the 170-foot structure as a historical landmark.” The City formally transferred the Tower to the Parks Department in 1955, along with the High Bridge, also removed from water service in 1949, and a section of the Old Croton Aqueduct.

After the Highbridge Water Tower was placed under Parks jurisdiction, the agency teamed up with the Benjamin Altman Foundation to install an electric carillon. This was a device imitating the sound of bells, allowing a building often compared to a medieval campanile to function like one. It debuted on Memorial Day 1958 with a 15-minute performance broadcast on WNYC radio.

The Altman Memorial Carillon, as it was called officially, chimed thrice daily on weekdays and twice a day on weekends for several minutes from speakers mounted in the old tank room. As Gay Talese of the New York Times observed in 1961, it “has served as a combination concert hall and alarm clock with such fidelity that many residents have let it run their lives.”

How long the five-octave carillon continued to operate is unclear. Periodically there has been talk of replacing it, but when members of the Parks and Cultural Affairs Committee of Manhattan Community Board 12 voted on capital project priorities in 2019, there was no support for this.

Undoubtedly the saddest day in the Highbridge Water Tower’s history is June 11, 1984, when a man broke in, set a fire in the tank room, and jumped to his death. This badly burned the cupola, which had wooden framework, destroyed the carillon, and caused other damage.

FromThe water-supply of the city of New York. 1658-1895. Published 1896.Public domain

In the late 1980s and early 1990s the Parks Department carried out a restoration, which included a new cupola. Although it looks generally similar to the original, there are aesthetic differences, including louvers in the middle section instead of windows. Also, the replacement weather vane has an arrow, whereas old drawings and photographs show something resembling a mythical aquatic creature.

Today, the cupola is reached via a spiral staircase in the center of the tank room though it is off-limits to the public. On the other hand, the original cupola contained a scenic lookout. A vestige of this are markings on the walls indicating the outline of the stairs that extended above the water tank (photo above).

Find out more about these and other facts and stories at our upcoming virtual talk about the Highbridge Water Tower on March 24th at 12 p.m. The event is free for Untapped New York Insiders. If you’re not a member, join now (new members get their first month free with code JOINUS).

A CONNECTION

Looking back on my family history it has much of a connection with today’s events. My maternal grandmother- Esther Silerrglate was born in St. Petersburg, Russia in 1888. My maternal grandfather-Charles Katz was born in Mogilev, Belarus in 1880, while my paternal grandfather-Philip Beridchawsky was born in Balta prefecture of Ukraine in1880. They all emigrated to the US in about 1900-1905 and settled in Philadelphia and Brooklyn.

I have visited the beautiful cities of St. Petersburg and Kiev to splendidly beautiful cities.

Words cannot express my sadness and praise for the people of this country.

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOU RESPONSE TO ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

IF BOUNCED-BACK SEND TO JBIRD134@AOL.COM

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

GEORGE WASHINGTON HIGH SCHOOL ON AUDUBON AVENUE

ANDY SPARBERG, HARA REISER, CLARA BELLA GOT IT RIGHT!

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

UNTAPPED NEW YORK

JEFF REUBEN

RIHS (C) FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment