Monday, January 30, 2023 – TIME FOR SOME DIFFERENT FOOD TONIGHT

LUNAR NEW YEAR CELEBRATIONS ARE CONCLUDING THIS WEEK, SO WE ARE TAKING A QUICK TRIP TO THE CHINESE CUISINE WORLD WITH STEPHEN BLANK.

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, JANUARY 30, 2023

ISSUE 899

Chinese Food in NYC – Answers and Questions

STEPHEN BLANK

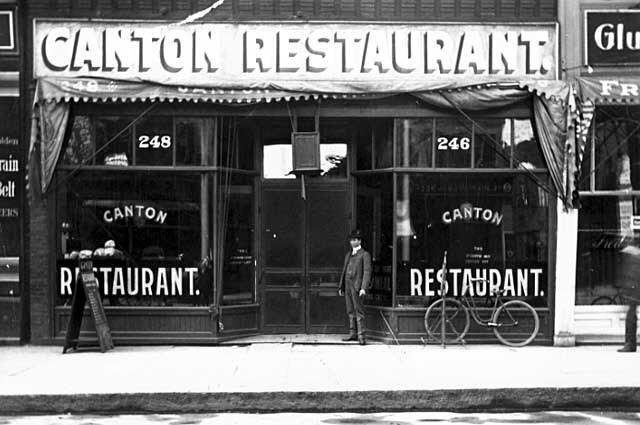

| I had Covid recently. No serious symptoms except extremely tired and loss of taste. My taste is now back, and I’ve been hankering for good Chinese food. Such thoughts trigger my research button and here we are. The first known Chinese restaurant in America, Canton Restaurant, opened in San Francisco in 1849. (By the way, today, according to the Chinese American Restaurant Association, more than 45,000 Chinese restaurants operate across the United States, more than all the McDonald’s, KFCs, Pizza Huts, Taco Bells and Wendy’s combined.) |

https://www.sidechef.com/articles/1519/chinese-food-fun-facts-general-tso/

The story begins with Chinese immigrants to California in the mid-nineteenth century—mostly from Canton province—drawn by the Gold Rush and fleeing economic problems and famine in China. Though some headed to the gold fields, most Chinese immigrants to the San Francisco Bay provided services for the miners as traders, grocers, merchants and restaurant owners.

Eating houses run by Chinese sprang up around town and won a reputation for high-quality food and unusually low prices. An all-you-can-eat meal could cost as little as $1 – less than half the price of what was available elsewhere. “The best restaurants,” one patron recalled, “were kept by Chinese and the poorest and dearest by Americans.” Chinese dishes were offered but much of what they served was western. One early menu lists “Grilled Dinner Steak Hollandaise” and “Roast California Chicken with Currant Jelly,” with “Fine Cut Chicken Chop Suey” presented as just another option.

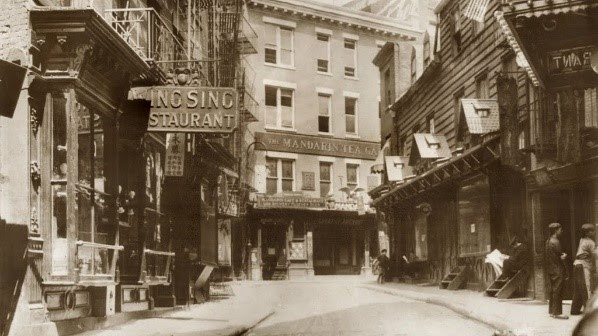

The next wave of Chinese immigrants came to work on the railroads, and Chinese food places grew up along the railway, spreading across the country. In 1855, 38 Chinese were recorded in New York, all males. Some early Chinese New Yorkers were sailors and traders who arrived directly in New York’s port and decided to stay, but many of our early residents arrived not from China directly, but from the western United States, particularly after anti-Chinese riots in San Francisco in 1877. In the mid-1870s, the New York Times counted around 500 Chinese immigrants, most of them men, half living in what now call Chinatown – the area defined by three streets that still form its heart: Mott, Pell, and Doyers.

Manhattan’s Chinatown: a tribute to the old neighborhood, and to the temptations of rich delicacies and basement vices

At this point, the story becomes confusing. The Chinese Exclusion Act forbidding Chinese immigration was passed in 1882 and the flow of Chinese was halted. At this point, there were only about 100,000 Chinese people living in the US – and no more could arrive legally until 1943 when the Exclusion Act was revoked. So, the number of Chinese entering the US was low: 14,800 in the 1890’s and a record low of 5,000 in the 1930’s.

But the number of Chinese restaurants in New York City seems to have increased – indeed, “by 1903,” an exhibit at the Museum of the Chinese in America said, “over 100 chop suey houses existed between 14th and 45th Streets, from the Bowery to Eighth Avenue” and the number of Chinese restaurants in New York City quadrupled between 1910 and 1920. We are told that late-1800s versions of New York hipsters head into Chinatown after new tastes for adventurous palates. They discovered the novel flavors of Americanized Chinese dishes like chop suey and egg foo young, popularizing them to the point that they spread throughout the city. Chinatown was “teeming” with people in the 1880s, we read. So, where did all these people come from? More light!

Was this “Chinese” food? And what the hell is Chop Suey?

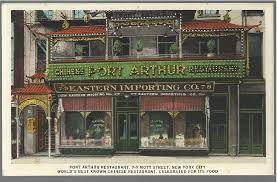

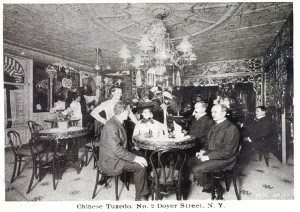

Different kinds of Chinese restaurants appeared in the City. Some were fancy, upmarket places. In 1897 Port Arthur Restaurant opened, the largest Chinese restaurant in the city. It became a magnet for “slummers” – American tourists looking to do something exotic in the evenings. They sat at mahogany tables inlaid with mother of pearl, listened to music played on a baby grand piano and congratulated themselves on their spirit of adventure. When Port Arthur became the first Chinese restaurant in the city to obtain a liquor license, it became even more risqué and fashionable. (Such an odd name: Port Arthur was a Manchurian city that Russia had forced China to lease it to them, as an ice-free navel base. It was seized by Japan in 1904. The whole thing was a symbol of China’s decay.)

Almost surely, it did not have an all-Chinese menu. In a 1903 article about Chinese restaurants, the Times described one patron who ventured to a Chinese restaurant: “A man might wish to treat his wife or a friend to a dish of chop suey after a theatre, but could not eat the stuff himself. He must either go hungry or be satisfied with tea and rice. Consequently he lets his wife have her chop suey, while he orders, from the American side of the bill, broiled ham or broiled chicken, according to how much money he wishes to spend.”

A high class “Chinese” restaurant. https://www.boweryboyshistory.com/tag/chinatown

Some very Chinese: Nom Wah Tea Parlor first opened at 13–15 Doyers Street in 1920 as a bakery and tea parlor. For most of the 20th century, Nom Wah served as neighborhood staple, offering fresh Chinese pastries, steamed buns, dim sum, and tea. Tourists came later.

Wah then and now. http://www.explorechinatown.com/Images/photomosaic/gallery20.html

Chop suey? In the 1920s American eaters were “shocked” when they were told “the average native of any city in China knows nothing of chop suey.” One food critic called chop suey “the biggest culinary prank one culture has ever pulled on another.” Others argue chop suey was indeed of Chinese origin. Where exactly its roots lay has been debated; but it was probably first cooked in Taishan, in Guangdong, where most early immigrants had grown up. More properly written tsa sui (Mandarin) or tsap seui (Cantonese), its name means something akin to “odds and ends”.

Was this an Americanized Cantonese cuisine? That’s what we were told. But anyone who has dined in a Cantonese restaurant knows that the cuisine is heavily seafood, very little like what we ate. Throughout the early 20th century, “Chinese” dishes became sweeter, boneless, and more heavily deep-fried. Broccoli, a vegetable unheard of in China, started appearing on menus and fortune cookies, a sweet originally thought to be from Japan, finished off a “typical” Chinese meal. Hardly Cantonese.

What is important is that an Americanized Chinese cuisine did emerge in the 1920s-30s – of various roots, but always looking to the customer’s tastes – and flowered after the war when immigration doors were open again. Regardless of its authenticity, the adaptation of Chinese cooking to American palates was a key element in the proliferation and popularization of Chinese cuisine in the United States.

This version of Chinese cuisine became the generic model – the Chinese restaurant menu in Buffalo was the same as in Detroit or, for that matter, in Winnipeg (and this is the truth, Lagos). Some restaurants were more upscale, some much less. But the cuisine was almost entirely the same. There were no surprises, no matter where we found a Chinese restaurant, it would taste the same.

Ultra-Americanized “Chinse” food (note “Chinese” is never mentioned). Wikipedia

From generic to regional specialization

In the 1960s and ‘70s, that generic Chinese menu underwent dramatic change. The Chinese restaurant community rapidly diversified its menus. Why? One reason was newcomers from different regions. The liberalization of American immigration policy in 1965 brought new arrivals from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and the northern provinces of China, who in turn brought with them the foods they had enjoyed in areas like Hunan, Sichuan, Taipei and Shanghai.

I think another reason was that younger, more educated Chinese realized that selling a commodity – the generic menu – would never make much money. They knew that the key was differentiation, developing new more focused products.

Finally, and a bit later, many better-off young people from China began coming to the US for education or jobs. To them, the generic American-Chinese cuisine made no sense.

The result in New York was grand – the opening of new Szechwan restaurants on the Upper West Side and then, hooray, Hunan on Second Avenue. Shanghai, Beijing. All sorts of new tastes. And then, Flushing.

But note, a recent GrubHub survey finds that old standards are still among the most often ordered: General Tso’s Chicken (also the 4th most popular dish of all), Crab Rangoon, Egg Roll, Sesame Chicken, Wonton Soup, Fried Rice, Sweet and Sour Chicken, Orange Chicken, Hot and Sour Soup and Pot Stickers. Not completely Old Timey, I guess, but hardly the cutting edge of Chinese food today.

https://www.mashed.com/237997/the-surprising-origin-of-chinese-takeout-boxes

What about Take-Out? Is that a Chinese invention?

First of all, people in cultures all around the world have long bought cooked food to bring home (see Pompeii). Certainly in China, where domestic cooking facilities were modest for most. So, doing the same in Chinese communities here did not mark a change. What is interesting is that non-Chinese joined in – and take-out became identified with Chinese food, and that Chinese restaurants adopted take-out as a brand. And long before today’s food delivery services, New York’s Chinese restaurant delivered. Why? When? Who?

The little paper box? Some say the boxes resemble the old pails used to bring home oysters. It’s certainly an American invention. Patented by inventor Frederick Weeks Wilcox in 1894, in Chicago, he called it a “paper pail,” a single piece of paper, creased into segments and folded into a (more or less) leakproof container secured with a wire handle on top. It’s not found in China. The question is “Is there a reason this particular container became so closely associated with Chinese food in the United States?”

And where did take-out in these boxes begin in the US – and when? Can we trace this back to a single restaurant?

I regret, dear reader, more questions than answers. And we can’t even trust a (non-Chinese) Fortune Cookie for to show us the way.

Thanks for reading,

Stephen Blank

RIHS

May 15, 2022

PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEEKEND PHOTO OF THE DAY

THE ENTRANCE TO THE 63RD STREET/LEXINGTON AVENUE F/Q

SUBWAY STATION.

LAURA HUSSEY GOT IT RIGHT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment