Thursday, February 9, 2023 – CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH AND SOME OF THESE SITES

FROM THE ARCHIVES

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 9, 2023

ISSUE 909

BLACK HISTORY

SITES TO

DISCOVER IN NYC

(PART 1)

UNTAPPED NEW YORK

Photograph Courtesy of NPS Photos

| The African Burial Ground National Monument is found in the Civic Center area of Lower Manhattan that contains the remains of more than 419 Africans from the 17th and 18th centuries. It is estimated that there were as many of 10,000 to 20,000 burials in the 1700s, and it is considered New York’s oldest African-American cemetery.In the 1600s, the Dutch West India Company brought over slaves from Angola, Congo, and Guinea, and by the mid-17th century, a village called the Land of the Blacks saw 30 African-owned farms in modern-day Washington Square Park. It was estimated that 42% of households in New York had slaves, which eventually totaled about 2,500 by 1740. Slavery was ultimately abolished on July 4, 1827, yet only one-third of the city’s blacks were free in 1790. The site was initially labeled on old maps as “Negro Burying Ground,” and the first recorded burials for people of African descent occurred in 1712, but it is speculated that the burial ground was in use two decades earlier.Some of the bodies of the deceased were illegally dug up for dissection, which sparked the 1788 Doctors’ Riot. The city shut down the cemetery in 1794, and urban development began taking place over the burial ground. The land remained largely forgotten until bones were discovered in 1991 during an archaeological survey by the General Services Administration. Protests occurred just a year later after it was discovered that the GSA had damaged some of the burials and took little care in excavation efforts. George H.W. Bush signed a law to redesign the area and to install a $3 million memorial, which was dedicated in 2007 to commemorate the role of Africans and African Americans throughout New York City’s history. In 1993 the African Burial Ground was designated a New York City Landmark and a National Historic Landmark. It is also a National Historic Monument. |

Seneca Village in present-day Central ParkSeneca Village was a settlement in the 19th-century in present-day Central Park, founded in 1825 by free blacks. With a population of around 250 residents at its peak, the village featured three churches, a school, and two cemeteries. Bounded by 82nd and 89th Streets, Seneca Village would exist for over three decades before villagers were ordered to leave due to the construction of Central Park.A white farmer named John Whitehead bought the land in 1824 and sold three lots of it to an African American man named Andrew Williams and twelve lots to the AME Zion Church. After the outlawing of slavery, many African Americans began to move into the village from downtown. A number of Irish immigrants fleeing the Potato Famine also settled in the village. Most of the homes were well-constructed, two-story buildings, the Central Park Conservancy tells us, rather than shanties which were in the minority of the buildings. Workers typically were employed in construction and food service, with many women working as domestic servants. The African Union Church in Seneca Village was one of the city’s first black schools, named Colored School 3.The Seneca Village Project, founded in 1998, was created to raise awareness of the settlement’s history as a middle-class, free black community. Today, a plaque commemorates the site where Seneca Village once stood. There have also been recent archaeological excavations to uncover traces of Seneca Village, and in 2011, researchers discovered foundation walls of the home of William Godfrey Wilson, who was a sexton for All Angels’ Church in the village. 250 bags were filled with artifacts during the digs, including the leather sole of a child’s shoe. Central Park recently celebrated the history of Seneca Village through new historic signage as well as free tours during Black History Month, of which Untapped New York partnered with the Conservancy to offer a special tour to our Insiders members. |

Historic Weeksville in BrooklynLike Seneca Village, Weeksville was a neighborhood that was founded by free African Americans, situated in modern-day Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Weeksville was founded in 1838 by James Weeks, an African-American longshoreman who bought land from Henry C. Thompson, a free African American land investor. The land was previously owned by an heir of John Lefferts, a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.By the 1850s, Weeksville’s population had surpassed that of Seneca Village, with upwards of 500 residents from across the East Coast, with over a third of residents born in the south. Weeksville was home to two churches, a school (Colored School No. 2), and a cemetery, as well as the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum. Weeksville also had one of the first African-American newspapers called the Freedman’s Torchlight and served as headquarters of the African Civilization Society. Additionally, the area was a refuge for many African Americans who left Manhattan during the 1863 Draft Riots. Four historic houses dating back to the time of the village collectively make up the Hunterfly Road Houses, listed on the NRHP in 1972. The discovery of these houses led to the creation of the Weeksville Heritage Centerdedicated to the preservation of Weeksville. |

Blazing Star Cemetery is in Rossville, Staten Island nearby the Sandy Ground communitySandy Ground was a community in Rossville, Staten Island, that was founded by free African Americans around the year 1828. Only a few months after slavery was abolished in New York City, an African American man named Captain John Jackson purchased land in the area, and the area quickly became a center of oyster trade. Many settlers would harvest and sell oysters at the nearby Prince’s Bay.Sandy Ground was also an important stop on the Underground Railroad, and the settlement is currently considered one of the oldest continuously settled free black communities in the U.S. A church, a cemetery, and three homes from the settlement are today designated as New York City landmarks, yet most of the original houses were destroyed in a 1963 fire. Today, the Sandy Ground Historical Museum is home to the largest collection of documents detailing Staten Island’s African-American culture, history, and freedom. |

A memorial in The Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground honoring the dead who are buried there.The Olde Towne of Flushing Burial Ground is a small burial ground alternatively known as the “Colored Cemetery of Flushing.” A large circular monument notes the burial of 500 to 1,000 people, primarily African Americans, Native Americans, and victims of four major epidemics of cholera and smallpox in the mid-1800s. Acquired by the town of Flushing in 1840 from the Bowne family, the burial ground contains the bodies of slaves and servants of the Flushing elite, as well as members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Death certificates issued in the 1880s confirm that more than half of the buried were children under the age of five. About 62 percent of the buried were African American or Native American.In 1936, Parks Commissioner Robert Moses decided to build a modern playground on the site of the burial ground. Local activist Mandingo Tshaka halted plans of renovating the cemetery to preserve its history. The Queens Department of Parks commissioned a $50,000 archaeological study in 1996 of the burial ground. In 2004, $2.67 million was allocated to this site, leading to the creation of a historic wall engraved with the names from the only four headstones remaining in 1919. |

PHOTO OF THE DAY

PLEASE SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

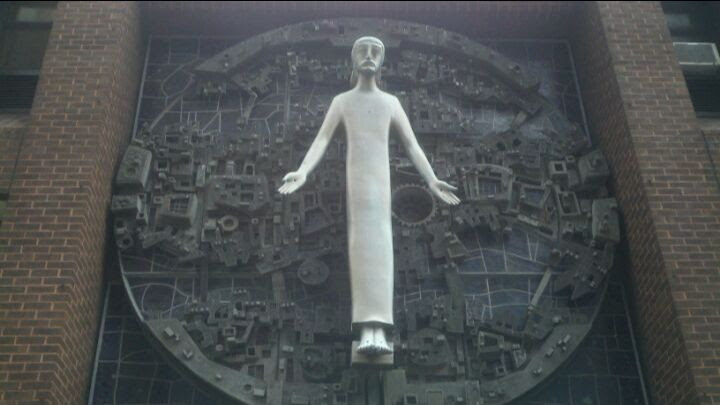

The Church of St. John the Baptist, located at 213 West 30th Street between 7th and 8th Avenues, has stood in Midtown since 1872. Designed in the French Gothic-style by architect Napoleon LeBrun, it first served New York City’s German population and was later assumed by the Capuchin Friars. In 1974, a brown brick Brutalist structure was added on the other side of the site at 210 West 31st Street, facing Penn Station, to serve as the Capuchin Monastery of St. John the Baptist.

The building now is closed and awaits if fate.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

UNTAPPED NEW YORK

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment