Wednesday, April 12, 2023 – TWO GROUPS WHO FOUGHT DISCRIMINATION BY BONDING TOGETHER

FROM THE ARCHIVES

TUESDAY, APRIL 12, 2023

ISSUE 962

The Seligmans, Philip Payton

&

Harlem’s Black-Jewish Alliance

NEW YORK ALMANACK

The Seligmans, Philip Payton & Harlem’s Black-Jewish Alliance

April 10, 2023 by James S. Kaplan

Around the time of the Civil War Joseph and Jesse Seligman were the most prominent Jewish businessmen on Wall Street – financiers of the Northern effort in the Civil War and close associates of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.

Every summer in the 1870s they would bring their families with a retinue of servants to stay at the Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga Springs, NY among the most prominent resorts in the United States. In 1879 however, the new manager of the hotel, Judge Henry Hitlon, announced a new policy — henceforth no Jewish people would be allowed to stay there.

The Seligmans were outraged and publicly denounced the policy. Although their efforts attracted some support from prominent christian clergymen such as Henry Ward Beecher, Judge Hilton stood his ground and the Seligmans efforts to overturn his anti-Semitic policy failed. In fact, Hilton’s policy was followed by more hotels following suit so that Jews were barred from hotels around New York State (leading to the rise of Jewish resorts in the Catskills, Adirondacks, and elsewhere).

Furthermore, Jews began to be excluded from residential neighborhoods, especially in Brooklyn, the Bronx and Queens. Many Jews at the time criticized the Seligmans for their boisterous opposition Hilton’s policies, arguing that it only made bigotry more prominent. The Seligmans responded by arguing that if anti-Semites could exclude the wealthiest and most established Jewish people in New York, how would poorer Jews, including those fleeing pogroms in Europe and Russia expect to be treated?

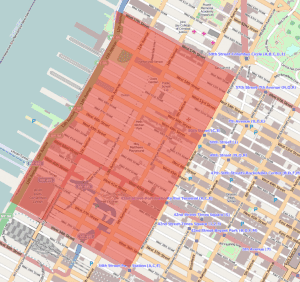

Ironically, one of the only upscale neighborhoods from which Jews were not restricted was Harlem, which by 1890 became home to one of the largest Jewish neighborhoods in the city.

Around this time there was also significant increase in discrimination against African-Americans in New York City. Most Black people were restricted to a slum area on the West Side of Manhattan called San Juan Hill (today Hell’s Kitchen) where they were forced to live in dilapidated housing. In 1900, after a Black resident killed an off-duty policeman leading to a riot in which police indiscriminately beat, arrested and tortured the area’s Black residents.

In the first decade of the 20th century however, through a surprising turn of events, the situation would change dramatically, when a young black college dropout from Westfield, Massachusetts, named Philip Payton got a job in a Hell’s Kitchen real estate office dealing largely with Black tenants. After taking a course sponsored by Booker T. Washington’s National Negro Business League, he quit his job with the real estate company to strike out on his own, advertising that he was a realtor specializing in Black tenants.

Payton noted that real estate developers had overbuilt in the northern part of Harlem around 135th Street and Lenox Avenue so there were many vacant or near vacant buildings whose rents were not much higher than in Hell’s Kitchen. However, Blacks people were restricted from living there because virtually no real estate owners there would rent to them.

As Payton would later tell it, one day a landlord on 134th street (presumably having difficulty filling their buildings) was fighting with another and threatened to rent his building to Black people. This landlord offered Payton a lease on his building if he could fill it. Through his real estate contacts in Hell’s Kitchen, Payton found Black tenants who were delighted to sublease apartments in the building from him at rents that were not too much higher than they were paying in the slums of Hell’s Kitchen.

From Payton’s point of view, he now had a fully rented building in a difficult market. Soon other landlords on the block contacted him to see if he could duplicate his success. Payton shortly had several buildings under management and his real estate business was prospering.

He was then approached by the Hudson Realty Company which offered to buy out his leases for an unusually high price. At first he was delighted at his good fortune, until he learned that the Hudson Realty Company was an agent for the Harlem Protective Owners Association and was evicting Black tenants. The Harlem Protective Owners Association sought to have all landlords in Harlem adopt restrictive covenants that barred them being rented or sold to African-Americans.

Payton found a real estate firm that owned properties across the street, Kassel and Goldberg, which agreed to work with him. Whatever their motives, the result was that the Harlem Protective Owner Association failed in its attempt to keep Black people off the block and ultimately was obliged to sell the buildings back to Payton. This gave Payton tremendous credibility and attracted attention throughout the city. Payton appealed for help from the Black business community, which was largely dominated by members of the National Negro Business League. Many of these members of the Committee were older men who had come to New York from the South, and were fearful that confronting the white establishment would risked violent reprisals.

Payton argued that conditions in New York City, with its various ethnic groups, was different. He argued that the time to take a stand against discrimination was now and the place was Harlem. The Jews that lived there also faced their own bigoted attacks and were more sympathetic. Jews like Kassel and Goldberg recognized that it was that if racial restrictions could be beaten in Harlem, they could defeat similar restrictions in the Bronx, Queens and Brooklyn.

Payton’s arguments largely carried the day and he formed a new company, the Afro-American Realty Company, capitalized with more than $500,000 contributed by the leading black businessmen in the city. This corporation issued a prospectus seeking contributions from Blacks throughout the City stated that the Company intended to practice “race economics” and attack racial barriers in housing.

Ultimately the company had a capitalization of more than a million dollars, making it one of the largest black-owned enterprise in the country at the time. Backed by the full weight of New York’s black business community, the Afro-American Realty Company began buying buildings in Harlem (sometimes through white agents) and moving black tenants into them.

A New York Times article of December 8th, 1904 entitled “Race War Breaks Out in Harlem Real Estate” described the company’s operations and the consternation that its activities brought to many white people living in Harlem. It’s estimated that within three years it owned more than 25 buildings (many of them renamed for black heroes such as Phyllis Wheatley or Crispus Attucks) and had more than 1,500 tenants under management. In his 1907 report of the National Negro Business League, Booker T. Washington said Payton, who he noted had been on both sides of an eviction proceeding, was one of the most prominent black businessmen in the nation.

Payton’s efforts to move African-Americans into Harlem faced virulent opposition from the Harlem Protective Owners Association and similar groups, but Payton retained the support of some landlords (including many Jews) who refused to join their efforts to keep Harlem segregated.

Although the Afro-American Realty Company became over extended financially and went bankrupt in 1908, Payton’s efforts to settle African-Americans in Harlem were continued by other black realtors such as John E. Nail, who were affiliated with wealthier black churches. In 1911, a critical row of previously all-white residences on 135th Street was purchased for a very high price by one of these churches (the “so-called “million dollar houses”). With this purchase, the Harlem Protective Owners Association collapsed and the area north of 125th Street quickly became a predominantly black community.

At a time when race relations in the South had reached a low point, word of the victory of the Afro American Realty Company and its successors in defeating racial covenants in the previously largely Jewish community of Harlem would spread through out the South and many African-Americans would buy one-way tickets to New York City, more than tripling the city’s black population.

James Weldon Johnson, head of the NAACP in New York wrote in 1925: “In the make-up of New York, Harlem is not merely a Negro colony or community, it is a city within a city, the greatest Negro city in the world. It is not a slum or a fringe, it is located in the heart of Manhattan and occupies one of the most beautiful and healthful sections of the city. It is not a ‘quarter’ of dilapidated tenements, but is made up of new-law apartments* and handsome dwellings, with well-paved and well-lighted streets. It has its own churches, social and civic centers, shops, theaters and other places of amusement. And it contains more Negroes to the square mile than any other spot on earth. A stranger who rides up magnificent Seventh Avenue on a bus or in an automobile must be struck with surprise at the transformation which takes place after he crosses One Hundred and Twenty-fifth Street. Beginning there, the population suddenly darkens and he rides through twenty-five solid blocks where the passers- by, the shoppers, those sitting in restaurants, coming out of theaters, standing in doorways and looking out of windows are practically all Negroes; and then he emerges where the population as suddenly becomes white again. There is nothing just like it in any other city in the country, for there is no preparation for it; no change in the character of the houses and streets; no change, indeed, in the appearance of the people, except their color.”

During the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s the neighborhood would become the unquestioned political, intellectual and cultural capital of Black America. Also, the benefits of the Black-Jewish alliance against racial and ethnic discrimination, which Payton had arguably forged with Goldberg & Kressel in Harlem, would soon become evident, as discriminatory covenants in real estate would be significantly reduced throughout the city.

Organizations such as the NAACP (headquartered in Harlem) and the Jewish Anti-defamation league would become major forces in the fight against racial and religious discrimination nationally as well, ultimately leading to the defeat of segregation and Jim Crow laws throughout the South.

Philip Payton, however, was largely forgotten and virtually nothing is known of Kassel and Goldberg. There is no monument, plaque or other recognition of Payton in Harlem or elsewhere, and there is no plaque marking the million dollar houses on 135th street, the purchase of which was so critical in the defeat of the efforts of the Harlem Protective Owners Association.

The financial empire of Joseph and Jesse Seligman was later eclipsed by rival Wall Street firms, and they too are largely forgotten today. Every New Yorker in New York State today stands in their and Philip Payton’s debt for their efforts to eliminate racial and religious discrimination more than 100 years ago.

On April 14th, 2023 at noon, the Lower Manhattan Historical Association will be awarding its Gershom Mendas Seixas Religious Freedom Award to William Tingling, the founder of Tour for Tolerance, an organization designed to educate African-Americans about the Holocaust and Jewish people about their common heritage in the struggle against discrimination. The award will be given during the annual ceremony commemorating the 1730 consecration of the Mill Street Synagogue, the first synagogue In North America, at 26 William Street in Lower Manhattan.

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

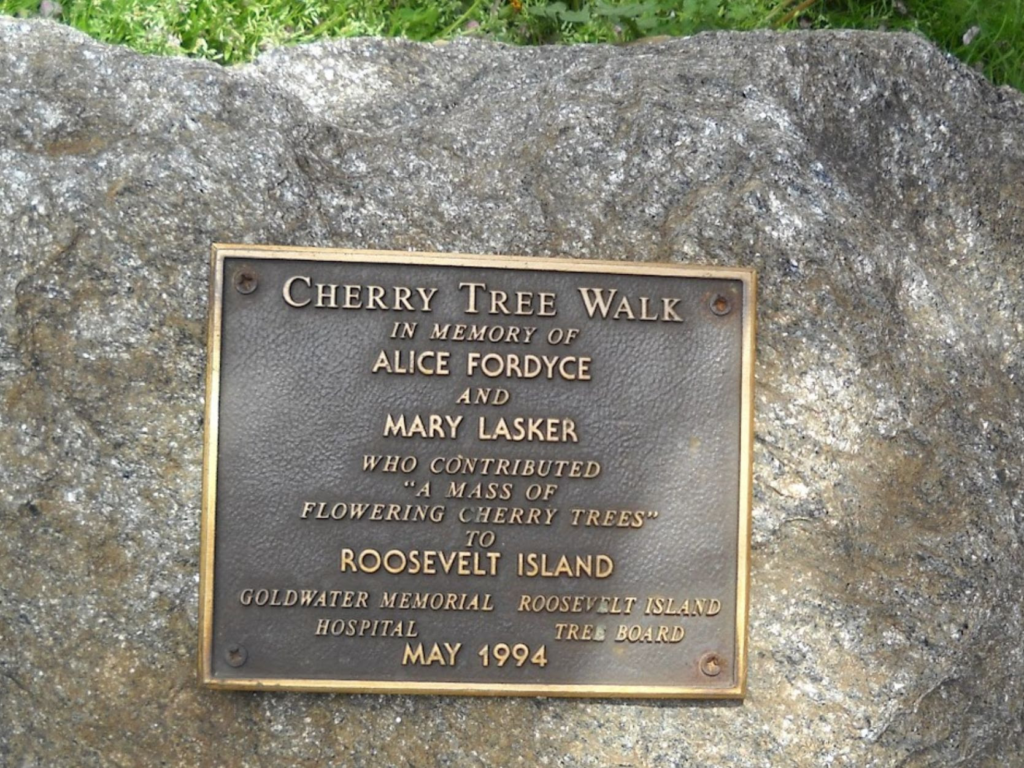

PLAQUE BY CHERRY TREES OPPOSITE SPORTSPARK ON WEST PROMENADE DONATED

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment