Wednesday, July 26, 2023 – A FASCINATING LIFE IN PARIS AND ABROAD

FROM THE ARCHIVES

WEDNESDAY, JULY 26, 2023

ISSUE# 1044

Josephine Baker

and

Illustrator Paul Colin

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Josephine Baker and Illustrator

Paul Colin

July 25, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp

A century ago this year, Josephine Baker traveled on a one way ticket from Philadelphia to New York City, having left her recently-wed husband behind.

Born an illegitimate child in a St Louis ghetto on June 3, 1906, Freda Josephine McDonald had a dismal childhood of poverty living in an area of rooming houses, run-down apartments and brothels near Union Station. The city was beset by racial tension and violence.

Independent and streetwise, Josephine was fourteen when she started performing with the busking Jones Family Band playing ragtime on street corners. Entertaining the crowd outside the Booker T. Washington Theatre, the band was invited by its manager to join the Dixie Steppers, a traveling group of vaudeville performers.

After ending the tour in Philadelphia, she found work as a chorus girl at the Gibson Theatre on the corner of Lombard Street and Broad Street. There she met and married Willie Baker, a Pullman Porter in his mid-twenties.

She started her career in New York in 1923 as a chorus girl in Shuffle Along, a landmark vaudeville revue in African-American theater by Noble Sissle (lyrics) and Eubie Blake (music). In September 1924 she performed in their two act Broadway musical Chocolate Dandies.

When the show closed in the spring of 1925, she took up an engagement at Harlem’s Plantation Club. Chicago-born impresario Caroline Dudley Reagan was a white patron of the club. She had a particular (commercial) interest in African-American music and recognized Baker’s talent.

In spite of doubt and anxiety, Josephine could not resist the offer to join the cast of a revue and travel to Paris where Reagan in consultation with her friend André Daven, artistic director of the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, had booked the theater for a series of performances.

Daven himself had taken advice from the Cubist painter Fernand Léger who suggested that hiring an Afro-American troupe would give the theater a much needed financial boost. It was there that Baker’s spectacular career took off.

A Match Made in Heaven

On September 15, 1925, young Josephine Baker joined twenty-five black performers (thirteen dancers, twelve musicians) who were set to sail for Cherbourg on Cunard’s flagship SS Berengaria. The company included pianist Claude Hopkins and his orchestra, dancer and choreographer Louis Douglas, blues singer Maud de Forest and the celebrated clarinettist Sidney Bechet. Rehearsals for the Revue Nègre took place during the crossing.

The show was produced by Rolf de Maré, a wealthy Swede living in Paris who was the founder of the vanguard dance group Ballet Suédois (Swedish Ballet). The Revue was staged at the Champs-Élysées Theatre on October 2, moved to the Theatre de L’Étoile in November, and was later shown in Brussels and Berlin, concluding in late February 1926.

On her arrival in Paris, Paul Colin had just been hired by André Daven as a set designer for the theatre. Born in Nancy in 1895, he had studied there under the Art Nouveau artist Eugène Vallin.

Having fought in the First World War, Colin settled in Paris and started work as a poster artist who incorporated modernist elements in his emerging stylistic repertoire. He was commissioned to create a poster advertising the Revue. After observing Baker in rehearsal, he enthusiastically invited her for a modeling session at his studio.

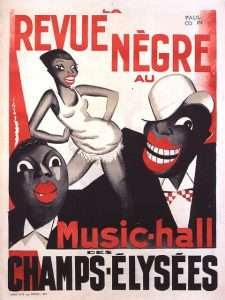

Colin’s poster in red and black colors shows Josephine in a tight white dress with short hair slicked back and fists on hips, appearing between two black men, one wearing a hat tilted over his eyes, the other with a broad smile. The Cubist distortion renders the rhythm of jazz. This joyous poster kicked off the careers of both Baker and Colin and would have a huge impact in the field of French poster art.

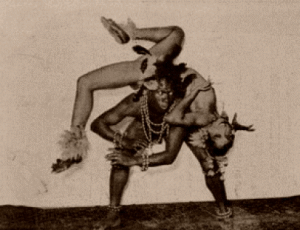

The Revue Nègre became a massive success. Baker performed three songs, but it was dancing with her Senegalese partner Joe Alex that thrilled audiences. They performed a “Danse Sauvage,” an uninhibited pas-de-deux in which both scantily clad performers were decorated with feathers and beads. The show opened to rave critical reviews and made Josephine an instant star.

The meeting of Baker and Colin was fortuitous for both of them. Baker found a devoted supporter who introduced her to vanguard artistic circles. Colin found a Muse who helped launch a career in which he produced some 1,900 posters and hundreds of stage and film sets. It made him the pre-eminent graphic creator in France. After a brief love affair, Paul and Josephine maintained a long-lasting personal and creative partnership.

Baker left the Revue in 1926 to star in her own show at the Folies-Bergère. The original troupe disbanded, but Baker’s star continued to rise as she performed to wild acclaim in clubs and theaters across Paris.

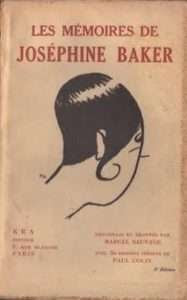

In her first acting role in the 1927 silent film La sirène des tropiques, she performed her legendary Charleston routine. Social jazz dance had arrived and Baker was its high priestess. That same year, aged twenty-one, she published her Mémoires with thirty illustrations by Colin.

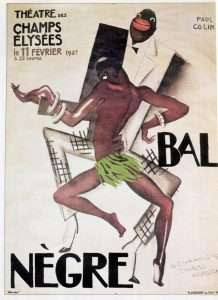

Also in 1927, Colin mounted a spectacular event called the “Bal nègre” which was attended by three thousand Parisians. During the late 1920s, Parisian nightclubs began hosting similar events which became main inter-racial social spaces.

Jazz & Art Deco

The musical language of American jazz differed fundamentally from the well-tempered European grammar that, at the time, had come under attack from young musicians who no longer were prepared to accept the cultural status quo. The “génération du feu” – a generation that had experienced the flaming hell of trench warfare – turned away from tradition.

For aspiring practitioners and composers, jazz represented a perpetual opposition to tired systems of musical establishment. The drive for continuous innovation was recognized by French modernists who used jazz as a strategic ploy to break well-established aesthetic rules and regulations. Post-war Paris was ready for Josephine Baker and eager to swing.

In 1929 Paul Colin created a portfolio entitled Le tumulte noir, soon to be acknowledged as a masterpiece of Art Deco graphic design capturing the exuberant musical culture that dazzled Paris. Published in an edition of five hundred copies and containing a title page, four pages of text (including a dedication by Josephine Baker) and forty-five sparkling lithographs printed on both sides of twenty-two sheets, it gave a name to the passion for African-American music and dance that Baker epitomized.

Colin’s vivid colours and lines expressed the Parisian fascination with all things black. Josephine herself is portrayed twice in this set. In one print she wears a skirt of palm leaves; in another her famous one of yellow bananas.

A double sheet rendering an orchestra performing against a fragmented Art Deco cityscape of ocean liner, skyscrapers and construction equipment, points to the band of the Revue led by Claude Hopkins. Another print shows Parisians ecstatically dancing the Charleston.

Art Deco proved a perfect stylistic means to honour the African-American contribution to French and European popular culture of that era.

Minstrel shows had reached London from the United States in the early 1840s and became the hottest musical attraction of its era. The fashion soon crossed the Channel to France. During the late 1840s Parisian cafés-concerts introduced the new sensation, featuring French singers with blackened faces and outlandishly red lips. By the turn of the century, these shows had become part of an entertainment scene in which African-Americans were typically portrayed as boisterous, but somewhat dim-witted characters.

To describe the passion for black culture, French critics used the term “négrophilie.” African art objects found their way into Parisian museums and art shops as a result of colonial trade. The vogue was inseparable from the latest tendencies in art and literature.

Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso and many other vanguard artists were attracted to African artifacts. Otherness intensified the clash between modernists and traditionalists: African carvings versus classical statues; jazz versus chamber music; Charleston versus ballroom dancing; banana skirt versus tutu.

Post-war Paris, on appearance, was becoming “color blind.” Baker’s beauty and blackness were intrinsic to her stage success. On the other hand, there can be no doubt that the Revue Nègre relied on (erotic) stereotypes of blackness. Baker’s “Danse sauvage” was an astute piece of exhibitionist art born from her understanding of racial stereotypes in general and their specific appeal in French cultural taste of the 1920s.

Baker’s sensual persona and revealing costumes were intrinsic to her success in Paris, but even more so were French stereotypes of the primitive and erotic African “Other.” It poses an intriguing question: who was exploiting whom?

An element of stereotyping was evident in Paul Colin’s poster as well. The suggestive pose of “La Baker” is intensified by the two male archetypal caricatures with thick red lips and frizzy hair. These types were lifted directly from the old minstrel show images.

The 369th Regiment of African-Americans, known as the “Harlem Hellfighters,” spent 191 days in French front line trenches, more than any other American unit and suffering 1,500 casualties in combat. Once the soldiers returned home, racial tension had not dissipated and remained rampant. Many former black soldiers decided to remain in France and turn to entertainment or hospitality for sources of income.

France may have had its own checkered colonial past, but the nation was grateful for the heroic participation of these soldiers on its behalf. Thankfulness alone however does not explain the astounding success of African-American music and dance in post-war France. Neither does the incredible professionalism of some of its performers.

Victory in war was won at a crippling cost. Of the eight million Frenchmen mobilized into the army, 1.3 million had been killed and almost a million were crippled for life. Large parts of its industrial and agricultural heartland in the northeast were devastated and depopulated. The value of the currency had collapsed; the economy was in tatters.

The psychological wounds caused by the strain of protracted warfare went deeper. The nation was battered and bruised by years of relentless fighting and the loss of so many young lives. A country in mourning had lost its vitality and famous “joie de vivre.”

African-American performers lifted the French out of a state of collective depression. Their rhythm, movement, energy and colour helped them to their feet and taught them to smile again.

Paul Colin’s work reflects that renewed drive in a fusion of French style and African-American vibrancy. It is to the artist’s credit that the old stereotype references were eliminated from Le tumulte noir. He created an iconic document in which the admiration for African art and African-American performers has found an exuberant expression. Colin’s portfolio is a dignified tribute to the spirit of Josephine and a celebration of the Jazz Age in Paris.

Ex-pat artists in Paris shared the enthusiasm for Baker’s performances. Writers such as F. Scott Fitzgerald and E.E. Cummings were inspired by Josephine’s beauty and sensuality. Ernest Hemingway referred to her as the “most sensational woman anybody ever saw. Or ever will.” Their devotion may have motivated her to return to the United States.

In 1936, she traveled to New York City to appear in a Ziegfeld Follies production on the Winter Garden Theatre stage with Fanny Brice and Bob Hope. The response was far from triumphant. A racist review in Time (February 10, 1936) typified Baker’s negative reception by theater-goers.

Its critic claimed that to a Manhattan audience Baker was “just a slightly buck-toothed young Negro woman whose figure might be matched in any night club show, whose dancing & singing could be topped practically anywhere outside France.”

Having cancelled her contract, a disheartened Baker returned to Paris. Before leaving, she divorced her estranged husband Willie Baker. Her ties with the United States were broken and she became a French citizen. Europe’s highest paid entertainer, she made her final triumphant appearance on the Paris stage at the age of sixty-nine. For once, Broadway had missed the (show) boat.

WE ARE NOW ON TIK TOK AND INSTAGRAM!

INSTAGRAM @ roosevelt_island_history

TIK TOK @ rooseveltislandhsociety

CHECK OUT OUR TOUR OF BLACKWELL HOUSE ON TIC TOK

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

TUESDAY PHOTO

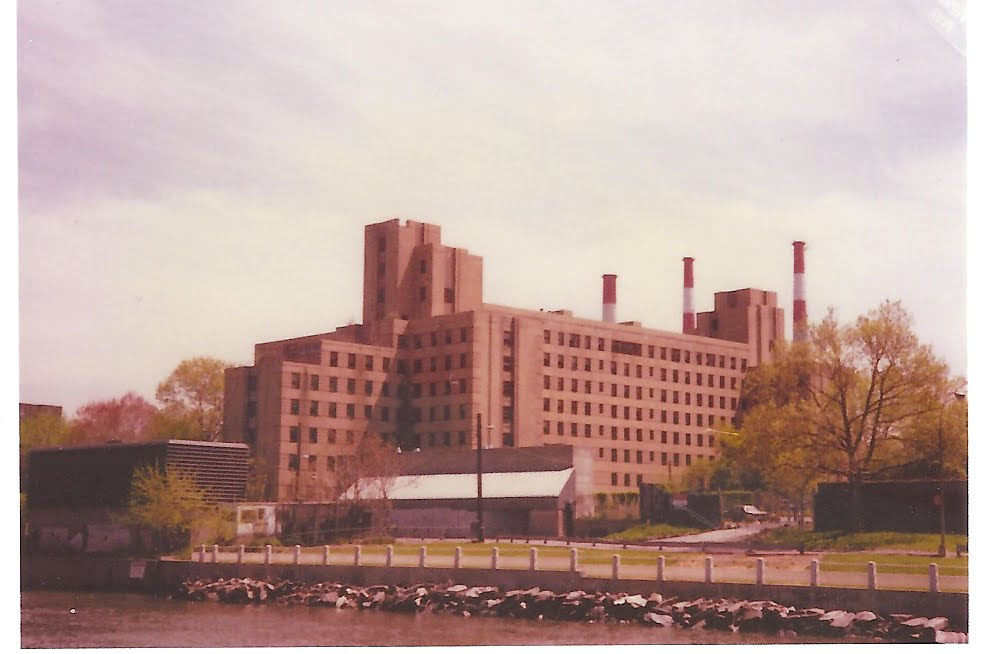

BROOKLYN ARMY TERMINAL

ANDY SPARBERG AND ARON EISENPREISS GOT IT RIGHT

THE VIEW OF “DOUBLE TAKE” FROM THE ROOF OF THE SUBWAY STATION.

TO SEE MORE OF DIANA COOPER’S ART AND PHOTOGRAPHS CHECK OUT HER WEBSITE:

dianacooper.net

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: Detail of photo of Joséphine Baker in 1940, photographed by Studio Harcourt; Paul Colin’s poster for the Revue Nègre; Baker and her partner Joe Alex in the “Danse sauvage”; Josephine Baker’s Mémoires with thirty illustrations by Paul Colin, 1927; Colin’s announcement of the “Bal nègre,” 1927; Cover of Paul Colin’s Le tumulte noir, 1929; Colin’s lithograph of the Revue Nègre band led by Claude Hopkins in Le tumult noir, 1929.

www.tiktok.com/@rooseveltislandhsociety

Instagram roosevelt_island_history

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment