Monday, April 22, 2024 – ALL THE PROFESSIONS THAT IT TOOK TO MAKE A SEAPORT

Thanks for dropping by at out table at Earth Love Day. We distributed 200 books, 150 backcpacks and signed up many islanders supporting our Q102 bus route. Thanks to Coler for the backpacks, to Materials for the Arts for the books. Most of all thanks to our volunteers: Moriko Betz, Thom Heyer Catheine Kim and Dylan Brown.

APRIL 22, 2024

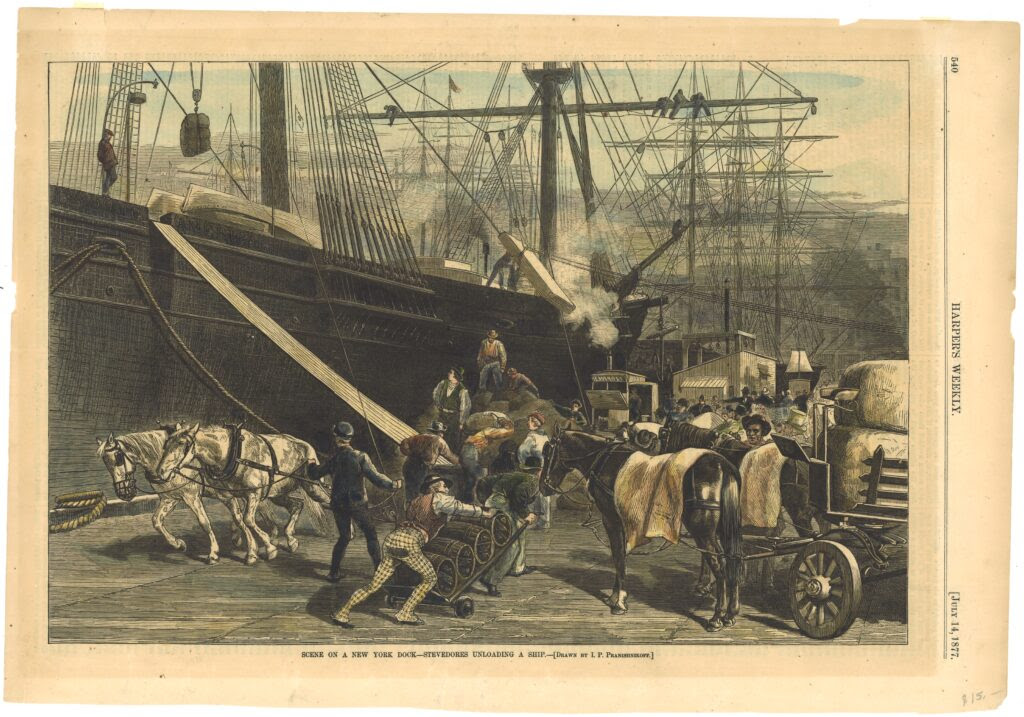

Labor on the Waterfront

Highlighting Professions

That Helped the Growth

of the

Port of New York

part 1

ISSUE # 1225

South Street Seaport Museum

A Seaport Museum Blog

by Carley Roche, Collections and Archives Intern

When thinking about New York City, what comes to mind? Usually tall buildings, crowded subways, and bustling streets filled with pedestrians. But if we peel back the urban layers we find there is so much more to discover. There are beautiful parks, a diverse wildlife, and an incredible coastline. With 520 miles of shoreline meeting rivers, bays, and the Atlantic Ocean- New York City boasts a remarkable waterfront. Along these different shores men, women, and children of all backgrounds have worked together trading and selling food, goods, and news with one another.

Labor Day is approaching as I write this post, and I wanted to highlight some of the professions that have been seen while walking along New York City’s vast coastline throughout the centuries, as I keep seeing them represented in the works of art I am cataloging and researching in the Museum’s collections. From working long months out on rough waters to endless hours manning a storefront, the following are just a few of the positions that have helped the Port of New York to become one of the most important locations in history, a national economic dynamo, and the busiest port in the Western Hemisphere by 1870.

|

In 1953, the Waterfront Commission was formed to stamp out this corrupt practice. By 1955, hiring halls had been set up at different locations along New York City’s waterfront for dockworkers to “badge-in”. This practice allowed the Commission to keep track of worker’s hours and dole out work according to seniority rather than economic status.

However, stevedore work in New York City plummeted around this time with the introduction of containerization. Large areas of space were needed for the new metal containers used to transport merchandise, which New York City could not provide.

[Dock workers standing outside Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor Employment Center 16], ca. 1965. Gift of the Waterfront Commission of New York Harbor, 1997.020.0021

The Red Hook neighborhood in Brooklyn is still home to a container shipping terminal, but by 1971, all other shipping companies had moved locations to New Jersey, thus essentially ending centuries long stevedore work in New York City.

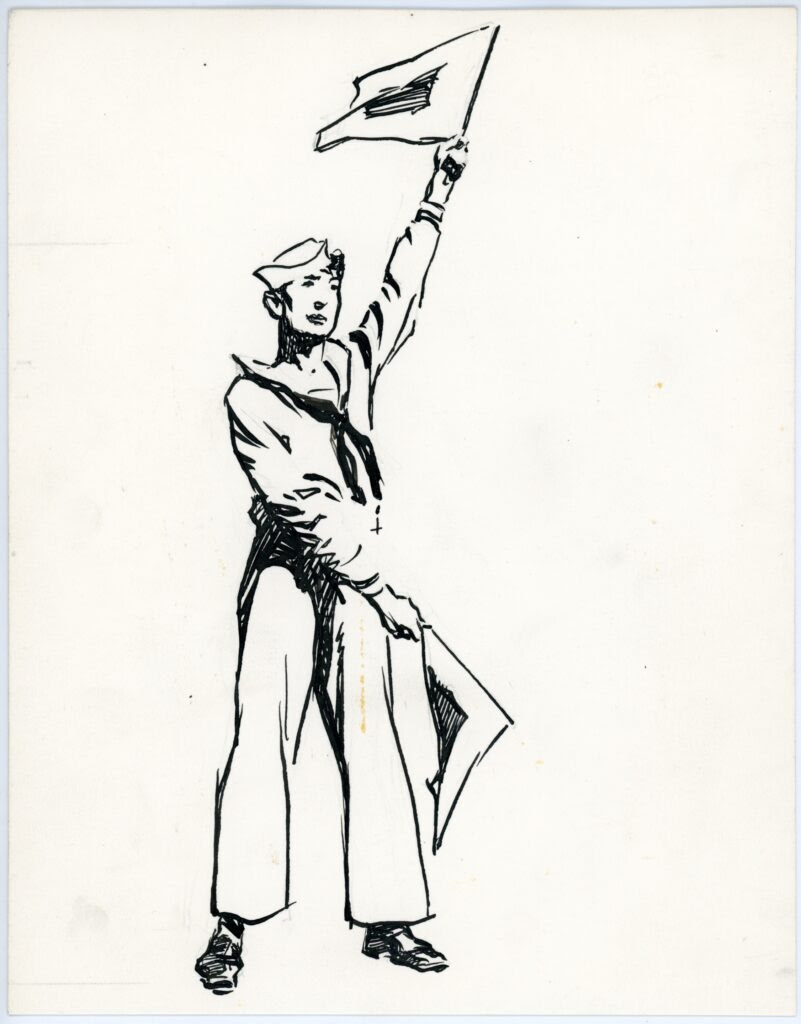

Sailors

Of course there would be no ships, ports, or merchandise without sailors. Ensuring the safe transportation of cargo to different cities all across the globe as well as maintaining whatever ship they were working on sailors have played a crucial part of trade and naval history.

Facing excruciatingly long journeys and extreme weather, sailors faced dangers on the seas to assist the maritime economy around the world. Sailors need to know navigational skills, cargo handling, the ins-and outs- of different vessels, and have general grit to last the long months at sea.

Much like stevedore work, sailors were heavily integrated despite American laws enslaving or restricting employment for Black people. “The close quarters, the shared hardship, the isolation from land-bound social forms–all contributed to a general lack of prejudice among seamen”[3].

Gordon Grant (1875-1962), “Sailor waving signal flags” 20th century. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection, 1991.071.0126

Many enslaved men were trained sailors outright, with records showing that many were sold highlighting these skills. Life at sea was a way to escape enslavement and earn a free living in free states and in foreign ports.

Women also found their way aboard ships, but in secrecy. Disguising themselves as men, women sought better wages or to live a life without gender-based restrictions[4]. The life of a sailor, though harsh and unforgiving, gave many men and women opportunities that were forbidden to them on land.

Printers

The Port of New York- with its merchants, grocers, and sailors- would not have been successful without the aid of printers.

At the heart of the maritime economy- newspapers, posters, stock certificates, pamphlets, ephemera, invoices, menus, job postings, etc.- printers and their assistants worked day and night to support the waterfront. Through their creations the area prospered throughout the centuries.

Print shops employed people of various backgrounds. Women could be found working less laborious positions such as editors, sales persons, or bookkeepers in shops run by male family members. Even if related to the printers, women would be paid less than men due to the belief men should be the main source of income for a family. Female printers were rare, often only taking over a printing business upon the death of a male family member[7].

Print shops even provided free Black Americans a place to work. Newspapers created by Black citizens, “such as Freedom’s Journal, The Struggle, the Colored American, the militant Ram’s Horn, and in the 1850s, the Anglo-American, informed the Black public of abolitionist efforts and indicated local examples of discrimination”[8]. Printing gave a voice and a vocation to people from everywhere. By 1900, New York City was home to over 700 print shops. In these stores, men and women printed news, images, stories, and business needs to support themselves and their communities.

The seaport district is home to New York’s City’s oldest and largest printing firm, founded by Robert Bowne (1744-1818) in 1775. Owner Robert Bowne initially opened the doors as a dry goods and stationery store then later adapted his business to cater to the growing needs of the bustling business area.

Later, Bowne & Co. specialized in financial and commercial business work on an international scale. Celebrating its bicentennial, Bowne & Co. Inc. partnered with the Seaport Museum to offer museum visitors a chance to experience a live 19th-Century print shop, which the Museum continues to do to this day at the Printing Offices at Bowne & Co.

MONDAY PHOTO

KWASAN CHERRY TREE NEXT TO KIOSK

Leave a comment