Tuesday, September 28, 2021 – A commentary that was written when the FDR FFP opened in 2012

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28, 2021

The

480th Edition

From the Archives

R.I. SPECIAL PARK

Today:

FDR FOUR FREEDOMS PARK

Past Perfect: Four Freedoms Park

The controversial politics of presidential memorials.

BELMONT FREEMAN

NOVEMBER 2012

The achievements of a postwar generation that brought to professional design practice a vigorous sense of mission — at once artistic, cultural, and political — are more evident than ever. In an ongoing and occasional series, historians and critics offer new assessments of modern masters.

An apparition has risen in the middle of the East River in New York City. A gleaming white vision of serene architectural perfection, it is also a specter from the past. I speak of Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park, the monument to President Roosevelt that Louis I. Kahn designed in 1973 and that only now has been realized. Commissioned at a moment when the New York State Urban Development Corporation was seeking to transform Welfare Island — a forlorn sliver of land that lies between midtown Manhattan and Queens — into a middle-class residential neighborhood, the project, situated at the southern tip of the island, was aborted after Governor Nelson Rockefeller and other political sponsors left office and as New York City, in the mid-1970s, slumped into near-bankruptcy. In the years that followed, attempts to revive the park floundered and Kahn’s design attained legendary status as his most compelling unbuilt work. Only after the turn of the 21st century, and in a vastly changed New York City, did the political, cultural and economic stars finally align to give life to the memorial project. It is a testament to the power of both the Roosevelt and the Kahn legacies, and a cause for rejoicing.

A deceptively simple composition, the memorial park is supreme Kahn, melding megalithic forms from ancient Egypt with modernist minimalism, while the strict symmetry and axial plan recall Kahn’s beaux-arts formation. One approaches from the north, mounting a broad set of stairs to a parterre of grass flanked by precisely aligned rows of trees. The lawn tapers and slopes downward, performing one of the place’s many tricks of manipulated perspective. The garden funnels attention onto a massive stone block with a niche that holds a larger-than-life-size bronze bust of FDR by the sculptor Jo Davidson, the one figurative representation of Roosevelt at the memorial. It is on the south side of the portrait altar that the prize space awaits; a square chamber open to the sky, which Kahn dubbed “The Room,” enclosed on three sides by 12-foot-high walls of white North Carolina granite and open on the south to a spectacular view down the river, encompassing the buildings of the United Nations, close across the water.

Stone platforms invite one to sit and read the inscribed text of FDR’s famous “Four Freedoms” speech and to contemplate the view. The craftsmanship is extraordinary. 1 The massive granite blocks that enclose the temple-like chamber — each reportedly weighing 36 tons — are set precisely level, with an open one-inch gap between the stones. The finely honed sides of the six-foot-thick stones bounce the light into one’s eye to uncanny effect. The cut slabs that comprise the battered walls of the twin ramps that lead from the memorial to the riverside esplanades — sloped in two directions and tapered — are specimens of stereometry worthy of a master mason of the Renaissance (cut and positioned, I am sure, by computer-guided machinery, but when Kahn’s office produced the design drawings no such aid was available). This is architecture that speaks to me, and in a familiar voice: I studied at the University of Pennsylvania while Kahn was still alive and teaching, and very much the dominant force at the design school. I feel Lou’s spirit here.

Louis Kahn, Sketch of Four Freedoms Park. [Image courtesy of Louis I. Kahn Collection, University of Pennsylvania and the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission]

Kahn’s site plan and renderings of the Four Freedoms Park carefuly compose the monument’s relationship to the river and to the United Nations, but they scantly reference any of the built infrastructure on Roosevelt Island (as Welfare Island was renamed in 1973), which at the time was home to several old and forbidding institutional buildings and the newly planned residential enclave then under construction. As it happens, the context is quite felicitous. Immediately adjacent to the park sit the remains of the 1845 Smallpox Hospital designed by James Renwick; a grim schist structure that is now a melancholy ruin. A reminder that the island was a zone of quarantine, the ruins of the hospital might also recall the destruction of war; bombed-out remnants of London or Dresden. As such they form the ideal prelude to the cleansing environment of Four Freedoms Park, through which one is delivered in stately progression to a vision of the United Nations and the possibility of a future without war. It is hard to imagine a more optimistic work of art, which delivers its message of redemption at the levels of material detail, human occupancy and the city at large.

I came away from my first visit to Four Freedoms Park exhilarated and uplifted, but those feelings were gradually replaced by mild depression. The fact is that in 2012 the optimism of Kahn’s vision is hard to sustain. The United Nations, which was founded with the utopian aspiration of preventing the recurrence of war, has proven ineffectual in that mission, riven as the institution is with mistrust and factionalism. The United States, universally admired in the immediate post-World War II period for its altruism and policies of social uplift, is now perceived by much of the world as a heavy-handed superpower intent on maintaining cultural, economic and military dominance — and provoking increasingly violent resistance in response. I also despair of the state of public architecture in this country. How telling it is, that our best new monument is one that had been cryogenically preserved for almost 40 years. I feel confident in positing that this FDR monument could not be designed today or, more to the point, would not be approved by any commissioning committee.

The Four Freedoms Park is too austere and insufficiently didactic. It leaves the viewer with too much interpretive leeway for today’s political and cultural climate in which scripted narratives prevail. Our society seems no longer able to invest meaning in abstract form. At least when it comes to the design of our monuments, Americans have lost faith in abstraction or, worse, have come to suspect abstract design as somehow masking a subversive message. Ever since Maya Lin’s masterful, geometrically pristine Vietnam Veterans Memorial (designed in 1981, which puts it much closer in age to Kahn’s FDR monument than to Michael Arad’s 9/11 Memorial) was accused of being a crypto-defeatist emblem of shame and subsequently compromised by the addition of “heroic” figurative sculpture, public monuments in the U.S. have been pressed to hew a didactic, representational design program. Thus the unencumbered, pluralistic expanse of the Washington National Mall — scene of massive public gatherings and historic demonstrations — was in 1997 interrupted by Friedrich St. Florian’s retrograde World War II Memorial; a composition with eagle-topped baldachins and neoclassical pillars clad in martial ornament, with fully advertent imperialistic overtones.

Top: Four Freedoms Park, aerial view looking south. [Photo: www.amiaga.com] Top center: Monumental stair. [Photo: Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park © Paul Warchol] Bottom center: Monumental stair and lawn. [Photo: Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park © Paul Warchol] Bottom: Four Freedoms Inscription. [Photo: Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park © Paul Warchol]

Now consider the sorry story of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial in Washington, D.C., the design of which is currently being fought over, behind the scenes and in the press. Frank Gehry, one of the greatest abstract artists of our time, inexplicably got himself entangled in the design of a monument of the most literal, representational type. According to the website of the Eisenhower Memorial Commission, the monument is to consist of two sets of sculptural groups depicting Eisenhower’s achievements as Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe and as 34th President of the United States. The larger-than-life-size statues are set on stone plinths and backed by slabs carrying texts. A third, centrally situated statue represents Eisenhower as a boy in Kansas, “looking out onto his future achievements”; a maudlin touch that has attracted considerable ridicule.

As if the heroic sculptural ensembles were not grand enough to honor the memory of a president distinguished by his personal modesty, Gehry Partners propose to surround the four-acre Eisenhower Square with 80-foot-tall “tapestries” made of woven metal — I’m sure they will dazzle — depicting the landscape of Kansas and elements of Eisenhower’s Abilene home. The screen rudely blocks the façade of the Lyndon B. Johnson Department of Education Building; not a lovely piece of architecture, but the affront is conspicuous. The alley thus created is euphemistically called the LBJ Promenade. (I can hardly wait until a commission is assembled and some hapless designer is engaged to design a monument to Lyndon Johnson.) The metal mesh pictorials remind me of gargantuan scroll paintings, or film strips that create the background, literally and narratively, for the sculptural groups that are the iconic “stills” from the Eisenhower story.

The official website notes that the sculptures will be in-the-round reproductions of famous photographs, perhaps to reassure us that the representations will be “objective,” and not subject to the interpretive license of some sculptor with unreliable motives. 2 What was Gehry thinking? Surely he would know that when you try to tell a story with such literal imagery you inevitably invite commentary and complaint; hence the well-publicized meddling by the Eisenhower family and members of Congress, who have been picking the Gehry design apart since it was first unveiled. 3 The imbroglio is a reminder that monument-making is not about the person whose life is being commemorated; it is about us, about the culture and politics of the moment and how we want the story to be told.

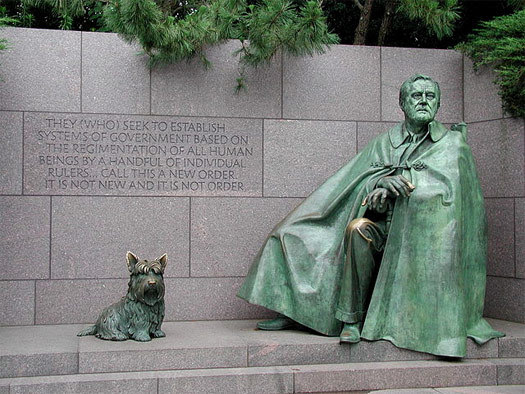

As I sought to contextualize Kahn’s Four Freedoms Park and Gehry’s Eisenhower Memorial, I recalled that the first modern American monument of the didactic, scenographic genre — at least as far as I know — was another memorial to Franklin Roosevelt. Located in Washington, D.C., and designed by Lawrence Halprin for a competition won in 1974 — making it contemporary to the Kahn FDR monument — the memorial was not funded and completed until 1997. Significantly, it is the work not of an architect or a sculptor, but of a landscape architect, who departed from traditional notions of monuments to create a themed park. The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial occupies seven and a half acres on the Tidal Basin and consists of four outdoor rooms enclosed by stone walls, plantings and water elements, and containing a collection of statues, bas reliefs and inscriptions that depict signal events in Roosevelt’s four-term presidency — the Great Depression, the War, a fireside chat, Roosevelt’s funeral cortege and so on. Eleanor Roosevelt gets her own niche with a statue that is, as I witnessed when I visited this past summer, the favorite photo-op spot for tourists.

Top: FDR Memorial, Washington, D.C. Sculpture of Franklin Roosevelt and Fala by Neil Estern. [Photo: Raul 654, courtesy Wikimedia Commons] Bottom: FDR Memorial, 1945, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C. [Photo: Nick-D, courtesy Wikimedia Commons]

The various sculptures are the work of an estimable group of artists, including Leonard Baskin, Robert Graham and George Segal, who offer vigorous and stylistically disparate interpretations of their assigned chapters of the Roosevelt story. After the memorial opened, controversy was fomented by advocates for people with disabilities, who felt that the single statue of FDR, seated with his dog Fala, did not make it sufficiently explicit that Roosevelt could not walk. Consequently a “Prelude” scene was added at the entrance to the park, with a bronze statue of the president in a wheelchair. I’m sure that Roosevelt would have loathed this depiction. Throughout his administrations he assiduously avoided being photographed in a wheelchair or in any situation that highlighted his disability, as he did not want to be known as the crippled president. But, of course, it’s really not about him. I suspect, in fact, that FDR would disapprove of the entire memorial park, as effective as it is. Roosevelt once expressed his wish that any memorial to him be no more than a single block of stone, the size of his desk. 4 Just such a monument was installed not long after his death, at Pennsylvania Avenue and Ninth Street, in front of the National Archives — but such a simple memorial doesn’t work for us today. The various narrative tableaux of the FDR Memorial serve a purpose identical to that of the pictorial stained glass and altar decorations in a medieval cathedral, which was to instruct an illiterate population on the lives of Christ and the saints. I fear that we are back to the task of instructing a historically illiterate population that has little knowledge of Franklin Roosevelt or Dwight Eisenhower and what they did or why they should be remembered. They have to be shown.

Not far from the FDR Memorial stands the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial, dedicated in August 2011. Neither abstract nor scenographic, the MLK Memorial returns to the old-fashioned genre of the single heroic statue. Despite gargantuan scale that would feel more at home in a Central Asian dictatorship and some heavy-handed symbolism — King’s form emerges from “a rock of hope” extruded from “the mountain of despair” — the memorial has the often-neglected virtue of a single focus. I like the fact that in this memorial — unlike the proposed Eisenhower monument — simply representing the person of Martin Luther King, Jr. is considered sufficient; that there is no need to illustrate the events of his life in pictorial form. A humanely scaled wall with inscriptions of King’s indelible words provides more than adequate supporting material. Like Mahatma Gandhi, King was a principal protagonist and enduring symbol of a social and political movement that resists imaging other than singular personification.

The egregious flaw in the design of the King Memorial, however, is the siting. Located on the northwest embankment of the Tidal Basin, the statue has no choice but to fix its gaze across the water onto the memorial temple of the slave-owning president Thomas Jefferson, and to turn its back to that of the emancipator, Abraham Lincoln. The official MLK, Jr. Memorial website credits authorship of the memorial to ROMA Design, a San Francisco-based architecture, landscape and urban design firm with a portfolio of significant public work. Strangely, given the centrality of the heroic statue, the sculptor is nowhere named. I suspect that this is a deliberate effort to suppress the memory of the protests that surrounded the selection of the Chinese artist Lei Yixin for the job. Many supporters of the memorial project felt that the commission should go to an African-American artist, while human rights activists declared that a sculptor whose principal credit was a monument to Mao Zedong was unfit to produce a portrait of Martin Luther King (carved of Chinese granite, no less). Along with site selection, design and iconography, even the execution of a monument can become politicized.

The completion of the Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island is nothing short of a miracle. New York City and the world owe a deep debt of gratitude to Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park LLC, which persevered in raising money and moving bureaucratic mountains to complete the monument, and to the design and construction team that executed Kahn’s conception so expertly. 5 That Kahn’s austere design survived the process virtually intact is remarkable. The custodians of the vision successfully deflected political pressures to add didactic elements to the memorial proper. An interpretive visitors’ center that may or may not be built within the ruins of the old hospital should house any such content at a safe remove, and the call to remind everyone that Franklin Roosevelt was stricken with polio in midlife and physically disabled thereafter will be answered by the installation of a sculptural group in a landscaped park to the north of, and out of sight from, the Kahn-designed memorial.

Unlike at the FDR memorial in Washington and the proposed Eisenhower monument, which impose a narrative on the visitor’s experience, at the Four Freedoms Park in New York the visitor is ennobled with the trust — the freedom — to formulate his or her own thoughts in an unencumbered environment of serene tranquility. But design compromises are made. When I first visited Roosevelt Island in August, I marveled at the visual purity of the ensemble — the broad entry stair, the gracious sitting-height perimeter walls, the multiple stone platforms of The Room — true to Kahn’s design and perfectly acceptable in 1974 but clearly not in compliance with today’s hyper-protective codes. Returning in early October, I noticed the addition of stainless steel handrails on the stairs — elegantly minimal, but not part of the original design — and I was told that the lawyers and insurance carriers were still debating the installation of more safety barriers on a work of art that is neither a building nor a conventional landscape — a depressing reminder of how fear of litigation perverts the design process today.

The creation of a public monument is a fraught business these days — just ask Michael Arad, who drove himself to the brink of insanity defending his once-simple design for the memorial at the World Trade Center site. That the pristine work of an architect nearly 40 years dead should rise intact, in today’s contentious political, legal and aesthetic climate, is, again, a wonder. And how timely it is that the legacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt should be honored in such eloquent fashion at a moment when powerful political forces in this country seek to dismantle it. In the case of Four Freedoms Park, it is clear that the design itself gave propulsive force to the drive to complete the project, both through its clarity and visual power and with the awareness that this was New York City’s final opportunity to build a work — his last — by one of America’s greatest architects. In the end, Four Freedoms Park is as much a monument to Louis Kahn as it is to Franklin Roosevelt. Abstract form worthy of the noble abstract concepts that it honors — Four Freedoms Park tells us that there is hope, after all.

TUESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

THE LINDEN TREES HAVE THRIVED AND LEND A NEW

VIEW OF THE MEMORIAL

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

LIGHTHOUSE PHOTO

BY ELEANOR SCHETLIN

(C) RIHS

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

Source:

PLACES JOURNAL

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS

CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment