Monday, November 21, 2022 – HE FOUGHT FOR THE AMERICANS WITH GEORGE WASHINGTON

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 21 , 2022

THE 839th EDITION

The Marquis de Lafayette:

A Short Biography

by James S. Kaplan

NEW YORK ALMANACK

The Marquis de Lafayette: A Short Biography

2024 will mark the 200th anniversary of the return of the Marquis de Lafayette (Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de La Fayette) to America. In 1824, almost 50 years after the start of the American Revolution, the 68-year-old Lafayette was invited by President James Monroe, an old Revolutionary War comrade and lifelong friend, to tour the United States.

Lafayette’s visit was one the major events of the early 19th century. It had the effect of unifying a country sometime fractured by electoral discord and reminding Americans of their hard won democracy.

In 2015, the French government and private groups raised approximately $28 million to build a replica Hermione, the French ship which had carried Lafayette to America in 1780 (his second voyage to here). That 1780 voyage is considered by some to have revived flagging Revolutionary efforts, and ultimately to have been a factor in the ultimate American victory, with French support, at Yorktown.

The replica of the Hermione, which was constructed by the French as a good will effort to highlight the historical ties between France and America, had a triumphant visit in 2015 to cities on the Eastern seaboard. The ship is currently in dry dock in Rochefort, France where it was constructed. You can read about that here.

The Marquis de Lafayette was born in 1757, at a time when England had largely defeated the French forces throughout Europe in the Seven Years’ War (the larger conflict that included the French and Indian War in the America). His family (and particularly his wife Adrienne) was one of the wealthiest in the country and was well-connected with the French monarchy. His father, a colonel of grenadiers, had been killed by the British at the Battle of Minden in 1759 (when Lafayette was two).

Like many young aristocratic Frenchmen, he had a desire to avenge the French defeats of earlier generations and a desire for glory in battle. Growing up in Auvergne, he attended private schools with the children of French nobility. When a revolution broke out in the 13 colonies America in 1775 he used his family resources and connections to fund his participation in the battle against the English and their allies.

In 1777, he voyaged to the British colonies to join the revolution then underway. At the time there were many young French adventurers who sought positions with the budding revolutionary army. General George Washington, eager to receive help from the French government, was informed by Silas Deane, the American ambassador in France that Lafayette was exceptionally well-connected with the senior levels of the French government, particularly the King. Washington added him to his personal staff (which also included Alexander Hamilton).

When the British were threatening Philadelphia, Lafayette was permitted to attend a council where the revolutionaries planned resistance to the British attack at Brandywine Creek. Washington was cautioned to take care that Lafayette not be put in danger. His death could provide the British with a great propaganda victory. At the succeeding Battle of Brandywine Lafayette saw the British begin to outflank the revolutionary army’s right under General John Sullivan. In the confusion of the battle, he rode out to the collapsing line and helped to organize an orderly retreat.

Wounded during the battle, Washington instructed his personal physician to treat him as if he were his own son. Thereafter Lafayette became a much more important American commander with whom General Washington would have a close relationship. Among the officers at Brandywine who attended to Lafayette when he was wounded was James Monroe, then a Virginia Militia Captain.

Lafayette then received a battlefield command of Continental soldiers in New Jersey, and was tapped by General Horatio Gates to lead an expedition from Albany into Quebec. It was hoped that French Canadians would rally to the revolutionary movement under Lafayette. For a variety of reasons, not the least of which was political intrigue and the lack of forces and equipment, the attack was never carried out.

Meanwhile his exploits received great acclaim in France where he became something of a national hero, and the pressure grew on him to return to France to see his wife and young child. Always in this period he was extremely active in trying to convince the French government to intervene on the side of the revolution with significant aid to the cause.

In 1780, with the American efforts at a low ebb, the king was finally convinced to send a substantial force under the Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, along with a French fleet. Lafayette helped lead this effort’s advance guard aboard the Hermione. From the revolutionary point of view, the arrival of Hermione was a ray of hope at an otherwise dark time. When the ship arrived in Boston, a large crowd was there to cheer it. Shortly thereafter, at his arrival in Philadelphia, Lafayette was greeted warmly by the Continental Congress.

The arrival of the French in force proved to be an important factor in the victory at Yorktown. Lafayette, as both an Revolutionary and French military leader, was intimately involved with the planning and execution of that victory.

Lafayette’s Return to France

After the American victory, Lafayette (then just 22) return to France and his young children and wife. Given a hero’s welcome for his role in defeating the British, he grew closer to King Louis XVI (two years older), to whom he often served as a kind of political and psychological adviser. After all, these young men had in effect avenged their country’s humiliation in the Seven Years War and forged an important relationship with the new United States.

The problems of a centuries old archaic and autocratic French society remained and both Lafayette and the king were also the inheritors of that legacy. The American Revolution had occurred in part according to the principles of Thomas Paine, who sought to overthrow monarchical and aristocratic society. The ultimate result would come just ten years later with the execution of the king and a long period of imprisonment and degradation for Lafayette.

During the opening events of the French Revolution Lafayette supported liberal reforms. As a member of the Estates General of 1789 he supported voting by individual delegates, rather than in blocks (known as Estates). In particular, before a critical meeting of May 5, 1789, Lafayette (a member of the “Committee of Thirty” argued for individual votes, which supported the power of the larger Third Estate (the commoners and bourgeois) over the clergy (the First Estate) and nobility (the Second Estate).

Lafayette could not convince the bulk of the nobility to agree with his position, and when the First and Third Estates declared the National Assembly on May 17th and were locked out by the loyalist supporting the Second Estate, Lafayette was among them. This led to the Tennis Court Oath, in which those locked out swore to remain together until there was a constitution. On July 11th Lafayette presented the original draft of the “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,” which he had written after consultation with Thomas Jefferson.

The next day armed revolutionaries assembled in Paris and two days later the Bastille was stormed. The day after that Lafayette was made commander of the Parisian National Guard (the Garde nationale), which claimed for itself the role of protecting and administering the city. Lafayette chose the Guard’s symbol, the red, white and blue cockade, forerunner of today’s French flag. The king and many loyalists considered him a revolutionary, but many of the Third Estate considered him to be helping to keep the monarchy in power.

In many ways Lafayette played the role of middle-man and tried to serve as a moderating force against the most radical revolutionaries. In early October, after the King rejected the Declaration of the Rights of Man, a crowd of some 20,000, included the National Guard, marched on Versailles. Lafayette only reluctantly led them in hopes of protecting the king and public order. When they arrived, the king accepted the Declaration but when he refused to return to Paris the crowd broke into the palace. Lafayette brought the royal family onto the balcony, and attempting to placate the crowd at one point kissed the hand of Marie Antoinette – the crowd cheered. Eventually the King was forced to return to Paris, changing the power of the monarchy forever.

Later Lafayette launched an investigation into the role of the National Guard in what is now known as the October Days, which was rejected by the National Assembly in protection of the ongoing revolution. The following spring the Marquis helped organize the Fête de la Fédération, on July 14, 1790 (the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille), a large convocation of more than 400,000 people at the Champs de Mars in Paris. At this event, representatives from around France and from all segments of society, including the king and royal family, who swore allegiance to a new liberal constitutional monarchy.

Among those swearing the oath to to “be ever faithful to the nation, to the law, and to the king; to support with our utmost power the constitution decreed by the National Assembly, and accepted by the king.” was the Marquis de Lafayette. During the ceremony the new 13-star American flag was the presented to Lafayette on behalf of the United States by Thomas Paine and John Paul Jones. It symbolized the support of democracy in both France and the United States.

Despite the Marquis’ best efforts, the illusionary unity of the Fete de Federation did not last more than a year. Loyalists thought the event threatened the king’s safety and diminished his power. More radical Jacobins saw the event as proof of Lafayette’s royalist tendencies and as an attempt to help keep the monarchy in power. Lafayette continued to support a moderate position which would protect public order in the coming months, including protecting the revolution in an armed stand-off with nobles known as the Day of Daggers in February 1791.

Lafayette’s National Guard was not always loyal to him, including occasionally disobeying his orders. In June, 1791 the king and queen escaped from the palace in Paris where they were being held under the watch of Lafayette’s National Guard. When he learned of their escape, the Marquis led the effort to recapture them and led the column returning them to the city five days later. The effect was devastating to Layette’s reputation however, as radicals, including Maximilien Robespierre denounced him as the protector of the king and the monarchy.

His reputation was further hurt when he led the National Guard into a riot at the Champ de Mars where the troops fired into the crowd, an event that was used for propaganda purposes by his personal and political enemies. After this incident, rioters attacked Lafayette’s home and tried to seize his wife. When the National Assembly approved the new constitution two months later, Lafayette resigned his position and returned to his home in Auvergne.

His retreat from the chaos of the revolution was only temporary however. When France declared war on Austria in April 1792, he commanded one of three armies. Three days later Robespierre demanded the Marquis resign his leadership position. He refused, and instead sought peace negotiations through the National Assembly. In June he became openly and aggressively critical of the radicals in control of the Assembly and wrote that their parties should be “closed down by force.” They also controlled Paris however, and finding his position increasingly untenable he left the city in haste. A crowd burned his effigy and Robespierre declared him a traitor.

On July 25, 1792 the Duke of Brunswick, Charles William Ferdinand, who commanded of the Allied Army during what is now known as the War of the First Coalition, threatened to destroy Paris, including its civilian population, if King Louis XVI was harmed. This radicalized the French Revolution even more. The king and queen were imprisoned and the monarchy abolished by the National Assembly. On August 14th an arrest warrant was issued for Lafayette.

The Marquis attempted to flee to the United States but was captured by the Austrians near Rochefort (in what was then the Austrian Netherlands, now Belgium). Frederick William II of Prussia (Austria’s ally against the French revolutionaries) had him held as a threat to other monarchies in Europe. For the next five years Lafayette was held a prisoner at various places, for some time with his family. He suffered harsh conditions, especially after a failed attempt to escape. He unsuccessfully attempted to use his American citizenship to argue for his release, although then President George Washington and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson successfully convinced Congress to pay the Marquis for his service during and after the American Revolution.

After his eventual release, Lafayette was allowed to return to France under Napoleon Bonaparte, on the condition he would not engage in political activity. He remained personally loyal to the democratic principles of the American and French Revolutions, but remained largely out of public life. He quietly opposed the centralized power of Napoleon, and publicly called on him to step down after the Battle of Waterloo. When the Bourbon Monarchy was restored he worked more actively in various European quarters to oppose absolute monarchy, including during the Greek Revolution of 1821.

1824 A Triumphant Return Visit to the United States

In 1820, James Monroe, his old comrade from the Battle of Brandywine, was elected President of the United States, with his Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, Monroe promulgated the Monroe Doctrine warning European powers not to interfere with matters in the Americas. In 1824, he invited Lafayette to return to the United States for a tour of the country as a national guest in honor of the upcoming 50th anniversary of the nation’s independence.

The purpose of the visit, among other things, would be to highlight the country’s unity. Electoral politics had been somewhat fractured in the United States in the previous two decades, including during the War of 1812 against France old nemesis, England. The visit would also indicate American support for democratic movements throughout Europe.

The King Louis XVIII found the American invitation to Lafayette insulting and caused troops to disperse the crowds that had gathered at Le Havre to see him off. His arrival in New York Harbor was met by dozens of ships and the tolling of bells. Its said that more than 50,000 well-wishers witnessed his arrival at Fort Clinton on the battery (later Castle Garden).

The procession up Broadway to City Hall, which would normally take about 20 minutes, took two hours. That evening a ball was held in his honor, at which veterans of the American Revolution moved him to tears.

Lafayette biographer Harlow Giles Unger described the festivities as follows:

“New York celebrated Lafayette’s presence for four days and nights almost continuously. Americans had never seen anything like it… He spent two hours each afternoon greeting the public at City Hall — trying to shake every hand in the endless line. Some waited all night to see him…. Women brought their babies for him to bless; fathers led their sons into the past, into American history, to touch the hand of a Founding Father. It was a mystical experience they would relate to their heirs through generations to come. Lafayette had materialized from a distant age, the last leader and hero of the nation’s defining moment. They knew they and the world would never see his kind again.”

In Boston Lafayette said: “My obligations to the United States, ladies and gentlemen, far surpass the services I was able to render.…The approbation of the American people…is the greatest reward I can receive. I have stood strong and held my head high whenever in their name I have proclaimed the American principles of liberty, equality and social order. I have devoted myself to these principles since I was a boy and they will remain a sacred obligation to me until I take my final breath…. The greatness and prosperity of the United States are spreading the light of civilization across the world—a civilization based on liberty and resistance to oppression with political institutions and the rights of man and republican principles of government by the people.”

The Marquis de Lafayette then visited towns and cities throughout the United States. His initially intended three to four month tour was extended to thirteen. A triumphal procession lasting more than 6,000 miles. In recognition of his service in the propagation of democracy in the United States, France, and Europe, Congress awarded him $200,000.

In 1917, when the Americans arrived to help defend France during the First World War, Colonel John E. Stanton declared “Lafayette, we are here!”

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

Send your response to:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

WEEKEND PHOTO

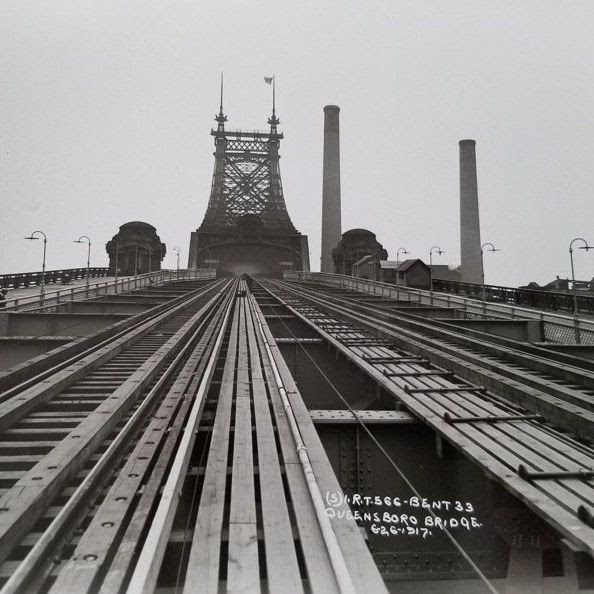

The top of one the eastern tower of the Blackwell’s Island, Queensboro,

59th Street, Ed Koch Bridge. The towers originally held flagpoies.

Andy Sparberg, Ed Litcher, & Alexis Villafane got it right.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

NEW YORK ALMANACK

SOURCES

illustrations, from above: George Washington and Lafayette at Mount Vernon, 1784 by Rossiter and Mignot, 1859; Lafayette in the uniform of a major general of the Continental Army, by Charles Willson Peale, between 1779–1780; Lafayette wounded at the battle of Brandywine by Charles Henry Jeans; Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen proposed to the Estates-General by Lafayette; Lafayette kisses Marie Antoinette’s hand on the balcony of the royal palace during a riot there in October 6, 1789; The Oath of LaFayette at the Fête de la Fédération on July 14, 1790; Lafayette as a lieutenant general in 1791, by Joseph-Désiré Court (1834); Marquis de Lafayette in prison, by an unknown artist; 1823 portrait of Lafayette, now hanging the House of Representatives chamber by Arey Scheffer.

THIS PUBLICATION IS FUNDED BY:CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE JULE MENIN AND DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment