THURSDAY, AUGUST 13, 2020 THREE UNIQUE ARTISTS

THURSDAY, AUGUST 13, 2020

The

129th Edition

From Our Archives

THREE ARTISTS:

THOMAS HART BENTON

PHILIP EVERGOOD

FRANCIS CRISS

THOMAS HART BENTON

Thomas Hart Benton, Wheat, 1967, oil on wood, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. James A. Mitchell and museum purchase, 1991.55

Watch brief YOUTUBE video about Achelous and Herculesmural and Wheat

https://www.si.edu/object/directors-choice-achelous-and-hercules-thomas-hart-benton:yt_ZW-HRtvIv1E

Thomas Hart Benton

Achelous and Hercules, 1947, tempera and oil on canvas mounted on plywood, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Allied Stores Corporation, and museum purchase through the Smithsonian Institution Collections Acquisition Program, 1985.2

Intense colors and writhing forms evoke the contest of muscle and will between Hercules and Achelous, the Greek god who ruled over the rivers. In flood season, Achelous took on the form of an angry bull, tearing new channels through the earth with his horns. Hercules defeated him by tearing off one horn, which became nature’s cornucopia, or horn of plenty.

Thomas Hart Benton saw the legend as a parable of his beloved Midwest. The Army Corps of Engineers had begun efforts to control the Missouri River, and Benton imagined a future when the waterway was tamed, and the earth swelled with robust harvests. Benton’s mythic scene also touched on the most compelling events of the late 1940s. America’s agricultural treasure was airlifted to Europe through the Marshall Plan as part of Truman’s strategy to rebuild Europe and contain communism.

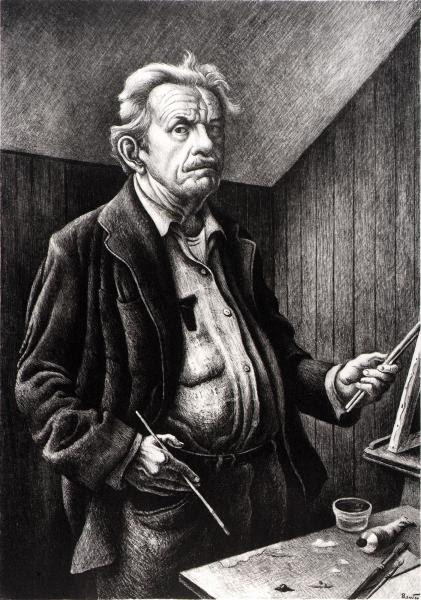

Thomas Hart Benton, Self-Portrait, 1971, lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase, 1972.102

PHILIP EVERGOOD

Philip Evergood, Workers Houses, Flushing Bay, 1935-1945, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Arnold and Augusta Newman, 1982.130

Many of Philip Evergood’s images protested the exploitation of America’s laborers, but this painting has a different quality. It focuses on the idea of home and community in the working-class neighborhood of Flushing Bay, in Queens. The settlement is not prosperous, but each house has its own plot of land and a few trees to soften the landscape. Smoke billowing from chimneys echoes the stacks of factories in the distance, where the people of Flushing Bay earn their living. The artist gave the painting to photographer Arnold Newman, and Newman later recalled his visit to pick it up in Evergood’s Greenwich Village studio. Evergood had decided that it needed “a spot of red here … He took out his paints and brushes and for four or five hours, long into the night, he reworked the canvas while I watched.” (Augusta and Arnold Newman to Adelyn Breeskin, December 28, 1982, SAAM curatorial file)

Dowager in a Wheelchair

Philip Evergood, Dowager in a Wheelchair, 1952, oil on fiberboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Sara Roby Foundation, 1986.6.90

Evergood’s art reflected a deep commitment to social equality and sympathy for human frailty. Recollecting the genesis of Dowager in a Wheelchair, he wrote, “Once I saw a tragic old lady being wheeled on Madison Avenue. She was alive in spirit but her body was only half functioning. She wanted still to be young. A young, gentle, fascinatingly fresh companion was wheeling her.

As I passed, spring was in the air, a delicate whiff of lilac perfume mixed with a faint background of crushed rose petals reached my nostril & then my brain. I was disturbed. I stopped when they’d passed and followed their progress through the crowds with my eyes. Taxis & cars were too noisy. I lost sight of them in a few moments. I went sadly on my way with a vivid memory which lingered on. I consider the painting to be one of the very best I ever painted.”

Modern American Realism: The Sara Roby Foundation Collection, 2014 Philip Evergood was a political radical who throughout his career sympathized with this country’s less privileged citizens. But his sympathy also extended to those whose wealth could not shield them from the realities of life.

Philip Evergood, Woman at the Piano, 1955, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc., 1969.47.57

Philip Evergood

was born in New York City. His mother was English and his father, Miles Evergood, was an Australian artist of Polish Jewish descent who, in 1915, changed the family’s name from Blashki to Evergood. Philip Evergood’s formal education began in 1905. He studied music and by 1908 he was playing the piano in a concert with his teacher.

He attended different English boarding schools starting in 1909 and was educated mainly at Eton and Cambridge University. In 1921 he decided to study art, left Cambridge, and went to London to study with Henry Tonks at the Slade School.

In 1923 Evergood went back to New York where he studied at the Art Students League of New York for a year. He then returned to Europe, worked at various jobs in Paris, painted independently, and studied at the Académie Julian with André Lhote. He also studied with Stanley William Hayter at Atelier 17. Hayter taught him engraving. He returned to New York in 1926 and began a career that was marked by the hardships of severe illness, an almost fatal operation, and constant financial trouble.

It was not until the collector Joseph H. Hirshhorn purchased several of his paintings that he could consider his financial troubles over. Evergood worked on WPA art projects from 1934 to 1937 where he painted two murals: The Story of Richmond Hill (1936–37, Public Library branch, Queens, N.Y.) and ‘Cotton from Field to Mill (1938, post office in Jackson, Ga.. He taught both music and art as late as 1943, and finally moved to Southbury, Connecticut, in 1952. He was a full member of the Art Students League of New York and the National Institute of Arts and Letters. He was killed in a house fire in Bridgewater, Connecticut, in 1973 at the age of 72.[3] He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn.[5]

FRANCIS CRISS

Francis Criss, Sixth Avenue “L” (mural, Williamsburg Housing Project, New York), 1937, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the Newark Museum, 1966.31.3

Francis Criss, City Store Fronts, 1934, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Transfer from the U.S. Department of Labor, 1964.1.35

Francis Criss Jefferson Market Courthouse 1935

Note that the Women’s House of Detention is in the background.

FRANCIS CRISS

Criss was born in London and immigrated with his family at age four. He attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1917 to 1921 on a scholarship, and later the Art Students League of New York and the Barnes Foundation, and he took private classes with Jan Matulka.

In addition to doing work for the U.S. Government under the New Deal, and contributing a mural for the Williamsburg Housing Project in Brooklyn for the Federal Art Project, Criss taught at the leftist American Artists School in the 1930s. His pupils there included Ad Reinhardt. He also held teaching positions at numerous other institutions, including the Albright Museum School, Buffalo; the Art Students League; the New School for Social Research; and the School of Visual Arts.[3] Criss was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship in 1934.

The work from his best-known years, the 1930s and 1940s, is characterized by imagery of the urban environment, such as elevated subway tracks, skyscrapers, streets, and bridges. Criss rendered these subjects with a streamlined, abstracted style, devoid of human figures, that led him to be associated with the Precisionism movement. With distorted perspectives and dream-like juxtapositions, as in Jefferson Market Courthouse (1935), these empty cityscapes also suggest the influence of Surrealism. A turn towards more commercial work later in his career—including a November 1942 cover for Fortune Magazine—led to a decline in his reputation.

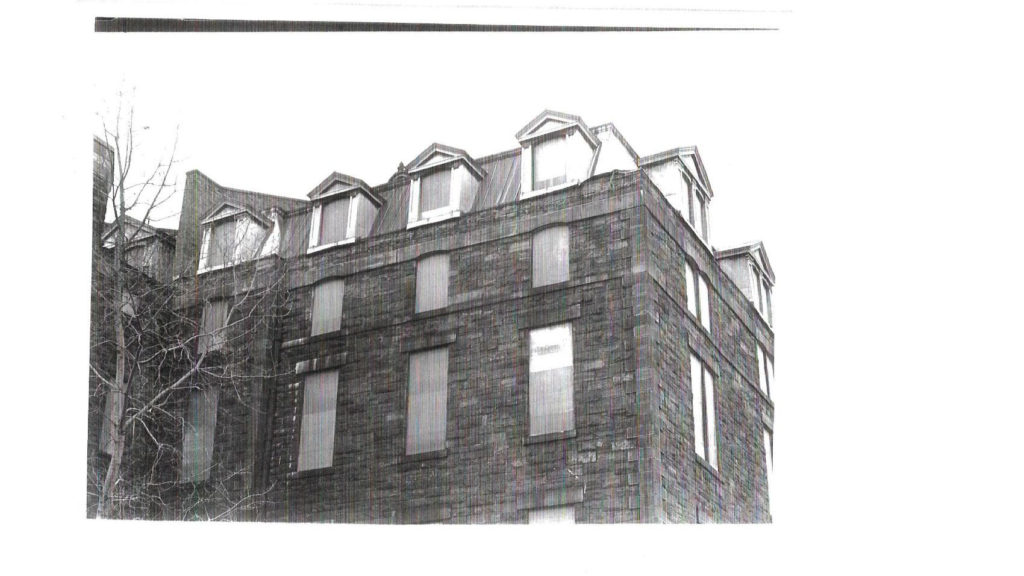

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR ENTRY TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WIN A KIOSK TRINKET

WEDNESDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

OLD CITY HOSPITAL

ITEMS OF THE DAY

FROM THE KIOSK

GREAT STUFF FOR ALL OCCASIONS

SUBLIMATED SOCKS $5-

KIOSK IS OPEN SATURDAY AND SUNDAY 12 NOON TO 5 P.M.

ORDER ON-LINE BY CHARGE CARD AT ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

EDITORIAL

The other day a friend and I wandered over to Long Island City. Parked by the Gantry NYS Park were a dozen food trucks. I could have had any variety of choices from empanadas to vege to Mexicano.

Why 12 food trucks here and ZERO on Roosevelt Island?

I am sure there is no reason to have 12 vendors on one site when a few of them could be on Roosevelt Island.

We have to stop the RIOC bureaucracy from scaring away any kind of vendor.

After 7 months of Pandemic I am very tired of the poor choice of dining and the sad state of our restaurants.

BRING ON VARIETY AND FOOD TRUCKS!!!

Judith Berdy

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

Roosevelt Island Historical Society

WIKIPEDIA (C)

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM (C)

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS

CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment