Monday, May 24, 2021 – Modernist and Expressionist Artist

MONDAY, MAY 24, 2021

THE

371st EDITION

FROM THE ARCHIVES

IRENE RICE

PEREIRA

ARTIST

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM

&

IRENERICEPEREIRA.COM

Welcome to the official website of Irene Rice Pereira (1902-1971). I. Rice Pereira, as she was known, was one of the foremost modernist artists of the 20th Century. Her paintings can be found in museums around the world.

The purpose of this website is to direct inquirers to her paintings, publications about her, museums and galleries exhibiting her work, archives and relevant websites.

Correspondence and original appreciations of Irene Rice Pereira’s work and life are invited. Images of Pereira works in museums are now on the Gallery page.

Courtesy Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

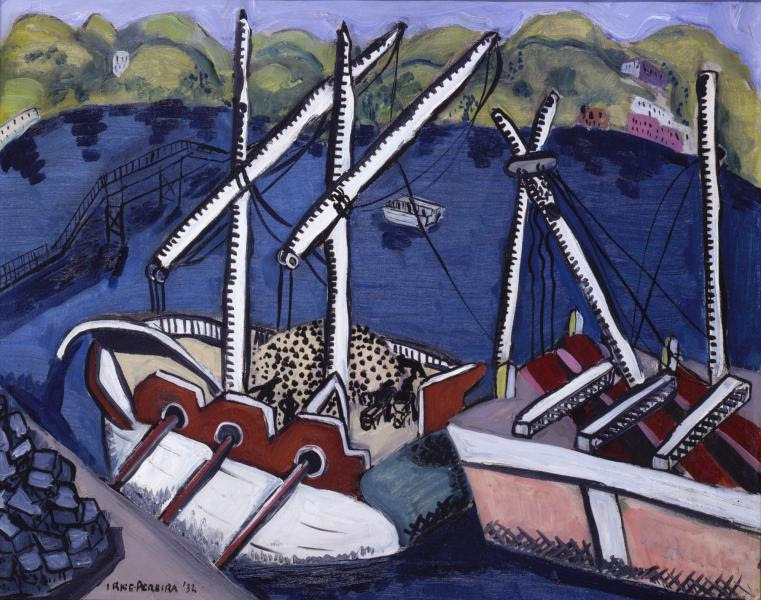

Born Irene Rice, she took the name of her first husband, the commercial artist Umberto Pereira. She adopted the name I. Rice Pereira because then as now discrimination beset women in the arts. By the time war broke out Irene had divorced Pereira and married George Wellington Brown, a marine engineer from a prominent Boston family. Brown was an ingenious experimenter with materials, and he encouraged his petite new wife in their mutual passion for experimentation. Pereira in the 1930s was drawn to ships, not only because of George Brown, but because of their intricate machinery, their functional beauty. The inside-out infrastructure of the Pompidou museum in Paris amused Pereira, although she thought it art-historically tardy.

Pereira visited Morocco briefly in the mid-1930s. The desert changed her life, filling her mind with pure light and purer forms, and had a crucial impact on her work when she returned to the United States to help found the Works Progress Administration Design Laboratory. The interactions of light and shadow among the dunes, playing in and around the intrinsically Cubist architecture of the Magreb, instilled in her a lifelong concern with optics, the way the mind perceives light and interacts with paintings.

Irene Rice Pereira was a lovely, fragile being. Her presence was hushed. She spoke almost in a whisper and listened far more than she spoke. She was a prodigious autodidact and a spellbinding lecturer. The main body of her metaphysical library today resides in the Museum for Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. Her papers and the manuscript for her still unpublished book, Eastward Journey, are available to scholars in the Schlesinger Library at Harvard.

Pereira won recognition for her abstract geometric work, particularly her jewel-like works on fluted and coruscated layers of glass, throughout the 1940s and early 1950s. In 1953 the Whitney Museum, then in Greenwich Village, gave her a retrospective exhibition with Loren MacIver, and that same year Life magazine published a centerfold photo examination of her work.

By the late 1950s Abstract Expressionism had swept Manhattan, flattening such nascent movements as Geometric Abstraction. Such artists as Stuart Davis, Stanton MacDonald Wright, George L.K. Morris, George Ault, Jan Matulka, Richard Leahy, Philip Guston and many others were eclipsed. Pereira believed that a European angst, brought to our shores in the wake of the Holocaust, had introduced a cynicism and a profoundly anti-female sensibility that boded ill for art in America. Rightly she pointed out that even when the works of women were acquired by museums they were rarely shown, a disgrace that persists to this day. The women who did achieve success, she said, were often collaborators with more famous male artists and tastemakers.

Pereira died in 1971 in Marbella, Spain, ill and broken-hearted. She had been evicted from the Fifteenth Street studio in Chelsea where she had painted for more than thirty years. Suffering from severe emphysema, she could barely negotiate a few stairs.

But by the 1980s a new generation of women scholars and curators had begun to resurrect her stature. A considerable following has formed to honor a pioneer artist who cared about other artists and willingly paid the price to denounce what others feared in silence. Indeed when Pereira sold a painting she had two immediate impulses: buy a new hat, and give the money to an artist friend in trouble. She loved hats but loved to help fellow artists even more.

I. Rice Pereira, Untitled (Boats at Cape Cod), 1932, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Djelloul Marbrook, 1988.80

- I. Rice Pereira, Sketch for Machine Composition #2, ca. 1936, pencil and crayon on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia and Phillip Frost, 1986.92.73

- Sketch for Machine Composition #2 was inspired by the view from the artist’s studio window. “I used to look in at a power house on 16th Street where I was living, to get the feeling of power house; and then made my own.” Fascinated by their functional beauty, Pereira made machines the central focus of her work in the 1930s. In this study for a painting, she presents devices that appear to have been taken apart and reassembled into a fantastic, abstract creation. Although she appreciated the potential of mechanization to transform society, this drawing has menacing overtones that suggest ambivalence.

I. Rice Pereira, Machine Composition #2, 1937, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Patricia and Phillip Frost, 1986.92.72

I. Rice Pereira, Heart of Flame, n.d., oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Max Robinson, 1981.184

Boat Composite, 1932, Oil on Linen, Whitney Museum of American Art

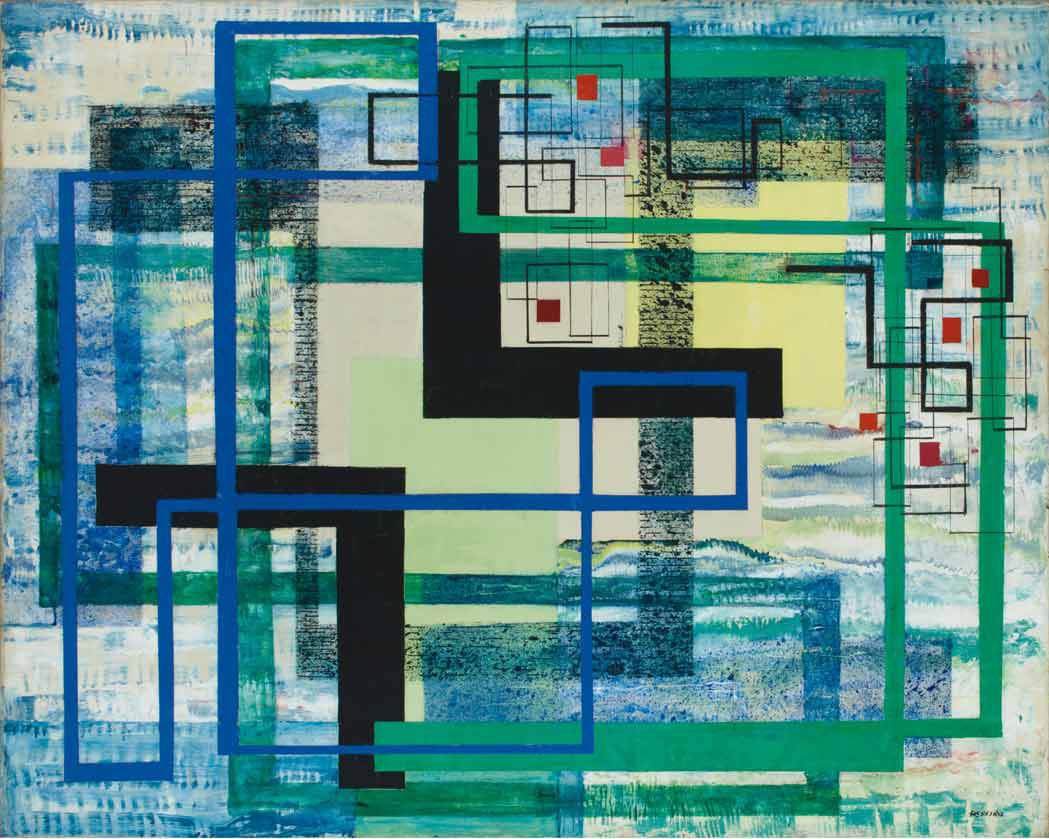

Seven Red Squares, 1951, Oil on Canvas, 40×50 inches, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Deborah and Ed Shein

Light is Gold, 1951, Glass, Acrylic, Laquer, Casein, and Gold Leaf, 30 1/8 x 23 1/4 inches, Addison Gallery of American Art at Phillips Academy

MONDAY PHOTO

Send your entry to ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

RESPONSES WILL BE PUBLISHED WEDNESDAY

WEEKEND PHOTO

Long Island Buddha, 2010-2011

Zhang Huan

(Location: Joseph Lau & Josephine Lau Roof Garden)

Zhang Huan is internationally recognized for his visceral and confrontational endurance performances in the 1990s and later sculptures and paintings that explore themes of memory and spirituality in relation to Buddhism. This sculpture was inspired by Zhang’s trip to Tibet in 2005, where he discovered fragments of Buddhist sculptures damaged during the Cultural Revolution. Rather than a religious image, this monumental Buddha head reflects on the history of human conflict and the preservation of culture. Included as part of ASHK’s inaugural exhibition Transforming Minds: Buddhism in Art in 2012, this sculpture now sits at the Center as a permanent installation.

ED LITCHER GOT IT, AFTER MUCH RESEARCH!!

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM

IRENERICEPEREIRA.COM

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment