Friday, February 17, 2023 – CELEBRATE BLACK HISTORY MONTH AND SOME OF THESE SITES

FROM THE ARCHIVES

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 17, 2023

ISSUE 916

THE 1872 PLAN TO GET AROUND

MANHATTAN VIA ELEVATED

PNEUMATIC TUBES

EPHEMERAL NEW YORK

The 1872 plan to get around Manhattan via elevated pneumatic tubes

The 19th century, not unlike today, New York City had a mass transit problem.

As the city’s population boomed and the urbanization of Manhattan continued northward, it was clear that the horse-pulled omnibuses and horse-drawn streetcars—which carried thousands of people to their destinations every day and contributed to enormous, epic traffic jams—were not going to cut it.

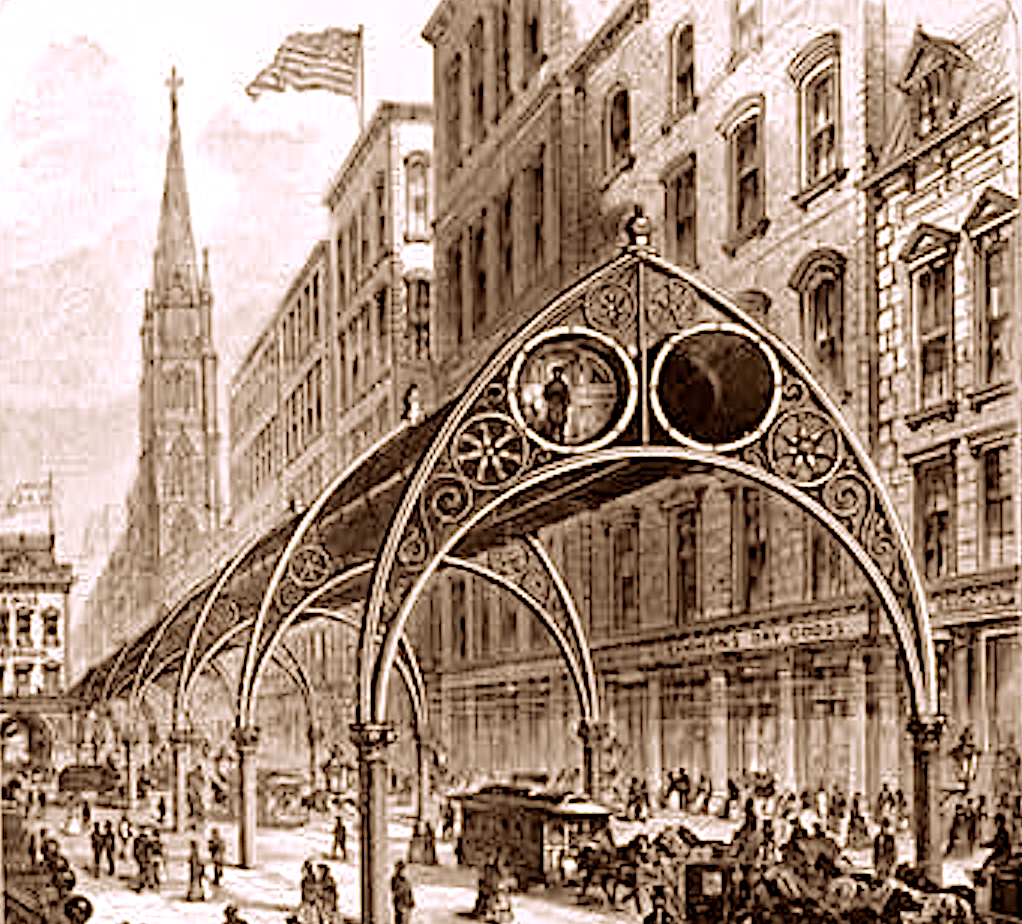

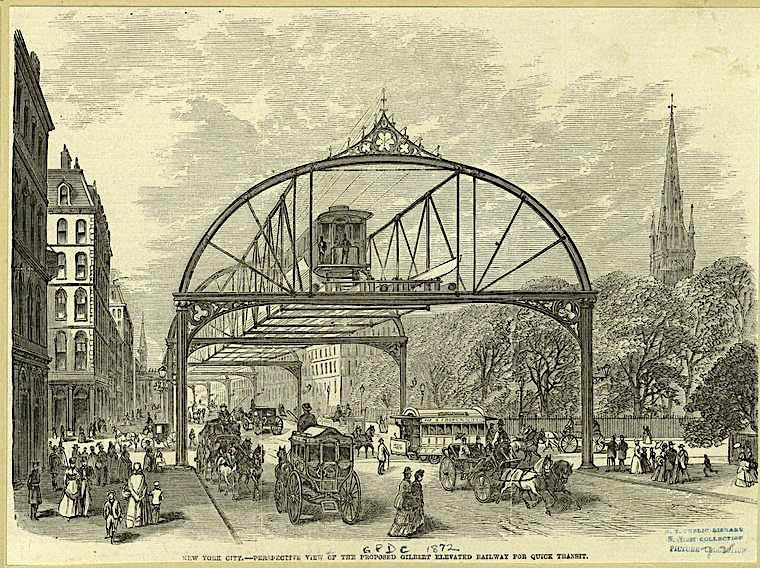

Enter the Gilbert Elevated Railway (above and below, in proposed illustrations). Introduced in 1872 amid a flurry of other ideas for elevated transit, this railroad would run high above the surface of the city on elegant, decorative wrought-iron archways, ferrying passengers in cars powered by compressed air.

Basically, it would be an elevated railroad shuttling uptown and downtown through pneumatic tubes.

The man behind the much-talked-about idea was Rufus H. Gilbert, a former doctor in the Union Army who was troubled by the high rates of sickness in tenement districts.

“Gilbert’s answer to the cholera, typhus, and diphtheria rampaging among the downtrodden classes was, elliptically, rapid transit,” wrote Sam Lubell and Greg Goldin in an article for The Gotham Center for New York City History.

“He reasoned that fast and cheap public conveyances would allow the poor to flee their teeming, disease-infested neighborhoods, and live in the hinterlands, where they could enjoy clean air and water, and plentiful sunshine,” continued Lubell and Goldin.

The idea of mass transit via pneumatic tube sounds a little crazy, especially if you think of pneumatic tubes as an old-fashioned system banks and department stores used to carry cash and receipts through a vacuum-powered network.

But it had precedent. Two years earlier, a pneumatic-tube underground subway opened for business. Running just one block from Warren to Murray Streets under Broadway, the city’s first subway, built by inventor Alfred Ely Beach, attracted curious riders—but not the funding (or political clout) needed to extend the line any farther. Beach’s subway closed in 1873.

Gilbert (above) may have borrowed the pneumatic tube idea, but he also put a lot of thought into how his railroad would run. He proposed putting his stations roughly one mile apart and providing pneumatic elevators for passengers to ascend to each station, according to Lubell and Goldin, who authored the 2016 book Never Built New York.

“He also planned a telegraph triggered by the passing cars, which would automatically signal arrivals and departures from all points along the line,” they wrote.

Though Gilbert got the go-ahead from the city to start constructing his pneumatic railway along Sixth Avenue, his plans had the misfortune of colliding with the Panic of 1873—a terrible depression that left him without investors. With no capital, he was forced to abandon his idea.

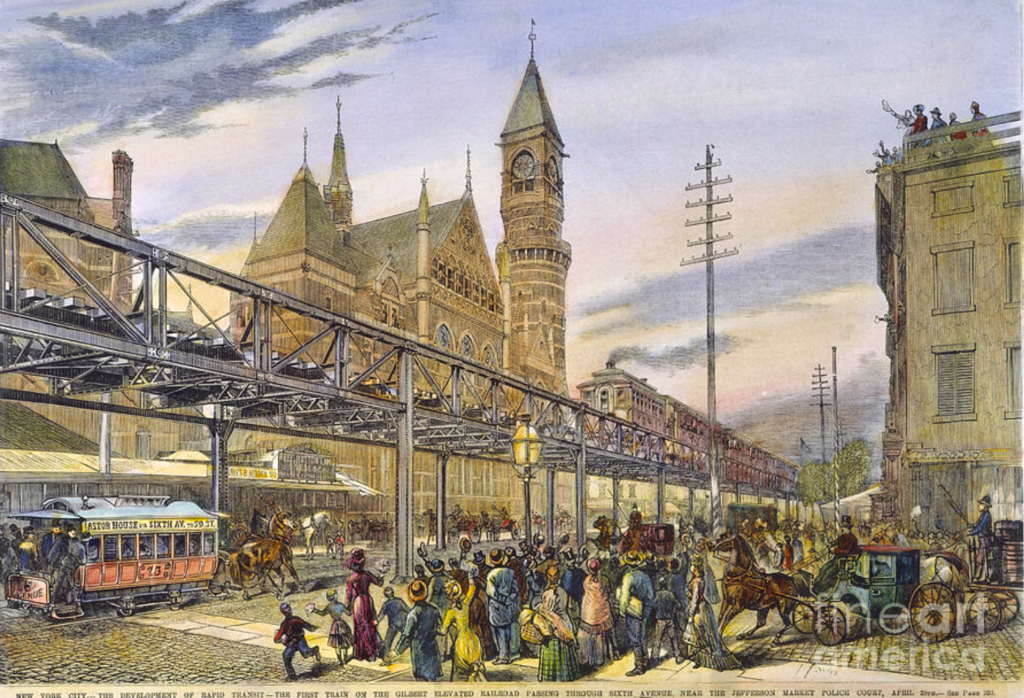

Gilbert persisted over the next few years, modifying his elevated railroad so it would be powered by steam engines, not compressed air. In 1875 he received a charter to begin building. Three years later, the first leg of the Gilbert Elevated opened from Rector Street to Central Park. (Above, the debut of the railroad as it approached Jefferson Market Courthouse.)

By 1880, almost all of New York’s avenues had steam-powered elevated trains roaring and belching overhead. Traffic congestion was relieved—but a decade later, plans for a faster, less obtrusive, and more efficient underground subway would be in the works.

What became of Gilbert? Sadly, after his elevated railroad opened, he was ousted from his own company, which was renamed the Metropolitan Elevated Company. Gilbert threatened to sue his former colleagues, charging that they defrauded him. Ultimately he died in his home on West 73rd Street in 1885.

[Top illustration: Alamy; second illustration: Library of Congress; third illustration: NYPL; fourth illustration: Library of Congress; fifth illustration: Library of Congress]

ANOTHER BLOCKED WINDOW

MAIN STREET HAS TURNED WHITED-OUT

PLEASE SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

FORMER DAY NURSERY AND P.I. 217 SIGN THAT USED TO BE ON RIVERCROSS WALL

NINA LUBLIN GOT IT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

EPHEMERAL NEW YORK

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment