Weekend, February 18-19, 2023 – STRUGGLING TO FIT INTO MANY SOCIETIES IN HIS LIFE

FROM THE ARCHIVES

WEEKEND, FEBRUARY 18-19, 2023

ISSUE 917

Sadakichi Hartmann:

A German-Asian-American

Artist’s Struggle for Identity

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Sadakichi Hartmann: A German-Asian-American Artist’s Struggle for Identity

February 9, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp

In response to the attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the founding of a new federal agency, the War Relocation Authority (WRA), which began forcibly removing Japanese Americans from the West Coast and relocate them to isolated inland areas. Around 120,000 people were detained in remote camps for the remainder of the Second World War.

Among those interned were artists. Chiura Obata had settled in America in 1903 and built a career as a painter and art teacher at the University of California. In the wake of events, he and his family were taken from their home and interned, first in Tanforan Centre, California, and then in Topaz Centre, Utah. Obata was involved in attempts to bring some “normality” into an existence of exclusion. He organized the creation of art schools for inmates. In addition to teaching, he created some 350 works during this period, including sketches that documented camp life. He communicated the spirit of survival, the unwillingness to accept defeat in the face of prejudice and humiliation.

An artist of mixed Japanese descent who managed to stay out of grasp of the WRA (in spite of persistent attempts by the FBI to “nail” him) was one of the most flamboyant characters in American cultural history of the early twentieth century.

Hamburg & Philadelphia

Sadakichi Hartmann was born in 1867 in Deshima, Nagasaki. That year also marked the end of the Edo period in which the artificial island was the sole territory in Japan open to Westerners. His father Carl Hartmann was an affluent Prussian merchant; his Japanese mother died shortly after giving birth.

Raised in Hamburg in the care of his grandmother and uncle, Sadakichi received a solid Lutheran education and was pressed as a teenager to attend the Imperial Naval Academy in Kiel. An independent mind, he rebelled against the academy’s Teutonic discipline and ran off to Paris. His furious father sent the youngster to Philadelphia.

Arriving in in June 1882, he spent three years with his paternal grand-uncle and wife, an elderly childless couple living at 806 Buttonwood Street. Hartmann struggled to cope with the dramatic change in lifestyle, especially since he – a spoiled young man shy of hard labor – was forced to earn a living by working at a lithographic printing house.

Books offered solace. He read voraciously at the Philadelphia Mercantile Library, eventually discovering Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman. Overwhelmed by his stylistic power, he visited the sixty-five-year-old poet at Camden, New Jersey, in 1884, starting what would become an intense relationship (as related in 1895 in his Conversations with Walt Whitman).

Having settled in Boston in 1887, Hartmann spent much of the following year in Europe. On return in 1889, he moved to New York City, residing in Washington Square, Greenwich Village, where he struggled with depression. After a suicide attempt, he met and married his nurse, Elizabeth Blanche Walsh.

Paris on a Tuesday

Whitman served as a model for Hartmann’s career. His early poems bear traces of Whitman’s influence; the title of his Drifting Flowers of the Sea and Other Poems (1904) is a reference to Leaves of Grass. His development as a poet was further enriched by his passion for the French avant-garde.

In 1891, Hartmann traveled to Paris as foreign correspondent for the monthly McClure’s Magazine, interviewing artists and covering scenes of cultural events in Paris. As “Japonisme” was all the rage in the visual arts then, he received a cordial welcome in the city’s artistic circles. Through his friendship with Stéphane Mallarmé, the chain-smoking poet, teacher of English and translator of Edgar Allan Poe, he was introduced to most prominent Parisian authors and painters.

Mallarmé, the “Prophet of Modernism,” was central to the avant-garde for the Tuesday night gatherings held +at his house on the Rue de Rome. Having visited one such occasions, Hartmann dedicated an essay (‘A Tuesday Evening with Stéphane Mallarmé’) to a description of the literary salon. He continued corresponding with the French poet as late as 1897. The impact of his stay was reflected in much of his subsequent art criticism and also in his plays and poetry.

In 1893, Hartmann issued 1,000 copies of his drama Christ, a symbolist treatment of Christ’s life complete with nudity and orgies. Almost all copies of the play were burned in Boston by morality activists of the New England Watch and Ward Society. Hartmann was arrested and spent Christmas week in the city’s infamous Charles Street Jail.

This controversial play was followed by another symbolist drama Buddha (1897). In addition to a number of other “religious” plays, he published various volumes of poetry. A collection of short stories entitled Schopenhauer in the Air appeared in 1899. All these works reflect the intense impact of his Parisian experience.

An American Art

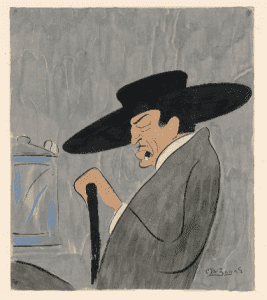

Hartmann had begun writing newspaper articles on art and literature in the 1880s. Whilst living in Boston, he launched his magazine The Art Critic. Its three volumes published in 1893/4 had a small readership of subscribers that included artists such as Albert Bierstadt, William Merritt Chase, Childe Hassam and others. Describing himself as an “American by choice,” Hartmann was on a mission. The magazine’s subtitle made his intention clear: “Dedicated to the Encouragement of American Art.”

His first article was “An Appeal to All Art Lovers” in which he called for the creation of a national art that would contribute to the “task of building up a new race from the waste of other nations.” A National Art would unite the country, making life richer for all. In an essay in the final issue he returns to the subject, stressing that a sense of Americanness could only be developed by cultivating a regional character and choosing local subjects – in other words: by challenging Europe.

Hartmann’s plea for an American Art coincided with his personal wish to obtain US citizenship, but there were serious obstacles. Until the 1952 Immigration Act, Federal law racially restricted naturalization which concerned citizens of Asian descent in particular as they were viewed as a group whose loyalty was in doubt. In 1894, a court held that Japanese people were not white; in 1909 and again in 1912, courts decided that people of half-Asian and half-white descent were not white.

In spite of that, Sadakichi obtained American citizenship in 1894. He most likely fooled the authorities. On his 1891 marriage certificate he was listed as “White.” Half a century later he would once again bamboozle officials about his background and status.

His art magazine was discontinued that same year, partly because he was too far ahead in his appreciation of Continental artists. His readers were (as yet) unreceptive to developments in France and Europe. Moreover, the legal defense costs of his Boston obscenity case had left him bankrupt. Hartmann was forced to take up journalism again. He returned to New York.

Prime Time NYC

Between 1898 and 1902, he penned more than 350 sketches on New York life for the New York Staats-Zeitung. Founded in the mid-1830s and nicknamed “The Staats,” it was at the time one of the city’s major daily newspapers.

Alfred Stieglitz launched his Camera Notes in 1898 and invited Hartmann to join the staff. During the next two decades, the latter was a prolific writer on art and photography for this journal and its successor, the more innovative Camera Work. Many of his pioneering contributions were published under the pen-name of Sidney Allan. He praised Eduard Steichen for showing the “courage to experiment and the ambition to break with conventional laws and to create new formulae of expression.” Art to him was about breaking rules.

Hartmann also covered New York’s visual art scene. His History of American Art (1901; revised 1938) was used as a standard textbook for many years. Other works of criticism include Shakespeare in Art (1900), Japanese Art (1903) and The Whistler Book (1910). Crowned King of Bohemia, he spent much of the 1910s in the Roycrofters Arts and Crafts colony in Upstate New York.

In 1904, he published an essay on “The Japanese Conception of Poetry,” discussing the precision and suggestiveness of forms such as tanka and haiku before similar ideas started circulating in French literary circles and among the Anglo-American Imagist poets. That year he included seven tanka in Drifting Flowers of the Sea. In 1926, he produced a limited edition of Japanese Rhythms.

Hartmann’s introduction of Japanese stylistic principles had an impact on the development of modern American poetry. Poets like Ezra Pound and Amy Lowell searched for alternatives to the pompous grandeur of Victorian poetry. Lowell modeled her work after ancient Greek and Latin examples, but Pound – thanks to Sadakichi’s intervention – found inspiration in Japanese precedents to push the boundaries of literary tradition. In Canto LXXX of his 1948 Pisan Cantos, Pound refers to Hartmann.

San Francisco & Hollywood

Hartmann arrived in San Francisco at the beginning of the First World War and quickly became a fixture in the city’s artistic community. As he refused to enlist or join the war effort, he was brought before a county judge who ordered him to work in the city’s Potrero Point shipbuilding yards. He sat on a rope coil and stared out at the Bay. He was returned to court and threatened with prison, but managed to talk his way into to giving public art lectures as his contribution to the cause.

Throughout his life, Hartmann had suffered from asthmatic attacks which became gradually worse, forcing him in 1923 to move to San Gorgonio Pass, a desert stretch between Los Angeles and the Coachella Valley. He became fascinated by Hollywood and worked for a while as a columnist for the English monthly theater magazine The Curtain. He even appeared in the bit role of court magician in Douglas Fairbanks’s “The Thief of Baghdad,” but his acting career was uninspiring and short lived. His creative powers were also fading.

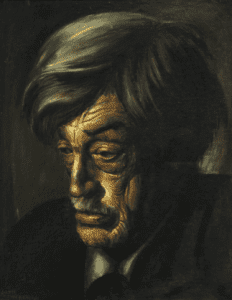

In Hollywood, Hartmann found himself adopted as a drinking companion by the actor John Barrymore and his mates, a group that often gathered in the Bundy Drive studio of John Decker, the painter who would create an iconic portrait of the ageing Sadakichi. As his health steadily deteriorated, he became dependent upon patronage from friends and admirers. His best work had passed into oblivion. By the 1920s, even former friends looked upon him as a scrounger.

Obituary & Legacy

With the outbreak of the Second World War the FBI started inquiring into Hartmann’s Japanese-German background. In numerous letters and confrontations, Hartmann pleaded with the authorities not to intern him. In the end, he confused them. What could they make of a mixed race person who in appearance was Japanese, who spoke English with a heavy German accent and who showed the refined manners of a French decadent; a person who, at the same time, was a proud American who had penned the first history of American art? Although the harassment never ceased, he escaped incarceration.

Hartmann retreated to Catclaw Siding, a shack adjoining his daughter Wistaria Linton’s home on the Morongo Reservation in Banning, California. There he composed his own idiosyncratic obituary, one that evokes the sounds of ringing bells and ocean waves that rise in disquiet at the poet’s imminent death. Its finale transforms into a more muted tone: “Sadakichi Hartmann is gone a new scene is on / Sounds like flowers drop one by one / Bing! Bang! Bung! Bing! Bong! / Bung! Bing! Bing! Bong! Bang!”

Hartmann died in 1944 while visiting another daughter, Dorothea Gilliland, in St Petersburg, Florida. Among possible titles for an unfinished autobiography Hartmann included Success in Failure (predating Bob Dylan’s classic line “There’s no success like failure”).

Today, he occupies a niche in cultural historiography. Hartmann failed in finding an audience for his work, because he never sacrificed his aesthetic principles for the sake of public approval. He published most of his poetry in limited editions, sharing his art with a select circle of readers. As he put it himself: “When only material progress is at stake, poetry does not function.” Hartmann fits the profile of a Continental modernist, but placed in the midst of an unprepared American setting. He acted as an intermediate in the transfer of cultural trends from Paris to the United States.

An enigmatic personality, his life was a restless search for identity, assuming various masks and guises: the French inspired dramatic poet of the 1890s; the prolific art critic of the turn of the century; the rebel who frequented Julius Schwab’s anarchist saloon at East First Street; the boozing King of Greenwich Village; and finally the ageing court jester in Hollywood. It was racial profiling and the bigoted reception of his work from the 1930s onward that damaged his reputation most. He was denied what he wanted most – to be acknowledged as an American author.

WEEKEND PHOTO OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

COVERED WINDOWS ON MAIN STREET. SOON TO BE A STREET WITH OUT IDENTITIES

PUP CULTURE, RIOC OFFICE, DR. RESNICK OFFICE

ALEXIS VILLAFANE GOT IT CORRECT

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

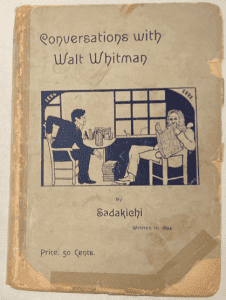

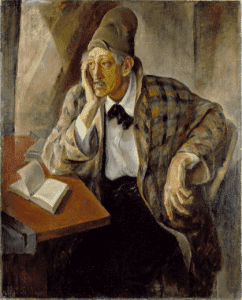

Illustrations, from above: Conversations with Walt Whitman; Sadakichi Hartmann, c. 1910 by Marius de Zayas (The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Alfred Stieglitz Collection); Cover of The Art Critic, (no. 1, November 1893); portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann, before 1934 by Ejnar Hansen (Los Angeles County Museum of Art); Sadakichi in one of his Mongol prince getups c. 1923; and portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann, 1940 by John Decker (Laguna Art Museum).

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment