Weekend, April 22-23, 2023 – A NEIGHBORHOOD THAT HAS HAD MANY TRANSFORMATIONS

FROM THE ARCHIVES

WEEKEND, APRIL 22-23, 2023

ISSUE 972

Chuck Connors

&

Slum Tourism in Chinatown

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JAAP HARSKAMP

Chuck Connors & Slum Tourism in Chinatown

April 20, 2023 by Jaap Harskamp

Dating from 1785, Edward Mooney

House at 18 Bowery, at the corner of Pell Street in Lower Manhattan’s Chinatown, is one of New York’s oldest surviving brick townhouses. Built shortly after the British evacuated New York and before George Washington became President, its architecture contains elements of both pre-Revolutionary (British) Georgian and the in-coming (American) Federal style. Designated in 1966 as a landmark sample of domestic architecture, Mooney House has three stories, an attic and full basement.

The property itself and the land on which it was built are manifestations of Manhattan’s socio-political emergence. The house harbors a history of various functions that involved a diverse mix of tenants and occupants, reflecting the chaotic rise of the metropolis.

Edward Mooney House

Born in New York in November 1703 (his father was a French Huguenot refugee from Caen; his mother descended from the prominent Dutch-American Van Cortlandt family), James De Lancey (Delancey) was educated in England, attended Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, before studying law at the Inner Temple in London. Having been admitted to the bar in 1725, he returned to New York to practice law and enter politics. In the course of his career he served as Chief Justice, Lieutenant Governor and acting Colonial Governor of the Province of New York.

De Lancey was also a substantial property owner. Known as “De Lancey’s ground” it included a 300-acre estate on today’s Lower East Side. Having sided with the British during the Revolutionary War, his land and assets were seized by the city’s authorities after the end of hostilities.

Part of the estate was purchased by Edward Mooney, a wholesale butcher and racehorse breeder. He erected the townhouse there, close to the slaughterhouses, holding pens and tanneries where Mooney made his money. He occupied the house until his death in 1800.

In 1807, the size of the house was doubled by an addition to the rear. It was in use as a private residence until the 1820s after which at various times the building served a range of purposes, including as a brothel, general store, hotel-restaurant, and pool room.

In the early 1900s the Edward Mooney House functioned as a tavern that gained a notorious reputation; Barney Flynn’s Saloon was a hangout for pugilists, gamblers, gang members and political hacks in an area that by then was referred to as Chinatown.

Chinatown

Manhattan’s ethnic enclave of Chinatown was born of exclusion. First established by Chinese merchants putting down roots near what was then a multi-ethnic port area. By 1870 there was a population of some two hundred immigrants. Soon after, these numbers increased sharply. During the post-1873 Long Depression, blatant discrimination in California and elsewhere drove large numbers of Chinese workers eastwards in search of employment in New York’s laundries and restaurants.

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (repealed in 1943), made it impossible for immigrants to legally enter the country. The law did not halt the flow of arrivals and their illegal entrance intensified racist prejudice in the wider society. In 1900, the US Census reported over 7,000 Chinese males in residence, but only 142 Chinese women. Chinatown was a “bachelor society.” The district was shared with various other groups of migrants. Its local funeral parlor served both Irish and Chinese customers.

George Washington O’Connor claimed that he was born in 1852 on Mott Street in Chinatown (he probably hailed from Providence, Rhode Island). Having changed his name to Connors to clear his presence of Irish associations, he became known as Chuck (for his love of chuck steaks which he cooked over an open fire in the middle of Mott Street). As a youngster he joined gangs that pestered Chinese citizens, but Chuck also learned to speak some Cantonese (which eventually endeared him to the local population). He subsisted on an Irish-Chinese diet of chop suey and potatoes.

Connors had a brief career as a professional prize fighter and then worked as a bouncer for James (“Scotty”) Lavelle, a gangster who ran several joints in Chinatown. He was a regular at The Dump, a saloon at 9 Bowery owned by Jimmy Lee and Slim Reynolds where criminal fraternities met and alcoholic ‘Bowery Bums’ gathered. Its clientele was described at the time as the ‘dirtiest species of white humanity.’

Inevitably Chuck got involved in criminality. His association with a thug named Big Mike Adams got him into trouble. Acting as an enforcer for local tongs (brotherhoods), Adams bragged he killed a slew of Chinese men by decapitating them. After the latter was murdered himself, a rumor spread that Chuck had been implicated in the attack. Having decided that Chinatown was too dangerous a place for him, he moved uptown, learned to read and write, and got married. Chuck took on a job on the Third Avenue El.

When his young wife suddenly died, Connors hit the bottle. Blind drunk one day, he was shanghaied onto a ship that set sail for London docks. He washed up in Whitechapel.

Spectacles of Deprivation

Deprivation in the Victorian period was associated with London’s East End. It was outside the Blind Beggar tavern on Whitechapel Road that William Booth founded the Salvation Army; it was here that social investigator Henry Mayhew researched his four-volume survey London Labour and the London Poor (1851); and it was in these slums that Arthur Morrison located his moving account of childhood suffering in A Child of the Jago. The East End was a nightmare, a gothic tale of distress that sparked deep indignation amongst social critics.

In literature and painting scenes of poverty and criminality were used in narratives to stir up a Cockney playhouse of images and emotions. Viewing the street as theater encouraged artistic license and misrepresentation. Sentimentalism and sensationalism were part and parcel of the process. Excursions into London’s poorest districts provided both scenes of bitter social hardship and accounts of crude merriment. There was an additional element.

Following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 a wave of pogroms swept across Russia and neighboring countries leading to mass migration to Britain and America. London’s Jewish population rose in the course of the next quarter of a century from some 47,000 to approximately 150,000, of whom some 100,000 lived in the East End.

These new immigrants formed tight-knit communities. Yiddish was used in signs, newspapers and in theaters. Local shops sold bagels, salted herrings and pickled cucumbers; kosher butchers provided brisket and salt beef. Itinerant Jewish hawkers dealt in second-hand wear and discarded household articles. It offered an urban spectacle never witnessed before in Britain. By the 1890s “slumming” in the East End had become a pastime for the rich. Colorful myths about Cockney life and familiar stereotypes about Jewish culture and people were expressed there and then.

It was in these harsh urban surroundings that Connors found safety and a sense of comfort. East End eccentricities appealed to him. Working for and with local costermongers, the itinerant traders who cried their trade lines (London Cries) to attract customers, he absorbed Cockney culture.

Mayor of Chinatown

Once returned to his Manhattan haunts, Chuck presented himself in an East London costermonger attire of bell-bottom trousers, blue stripped shirt, yellow silk scarf and a blue pea coat with big “pearly” buttons. He even adopted a Cockney song he had learned:

Pearlies on my front shirt,

Pearlies on my coat,

Little bit of dicer, stuck up on my nut,

If you don’t think I’m de real thing,

Why, tut, tut, tut.

Instead of an East End flat cap, Connors wore a derby (a “dicer”) that was two sizes too small with a nod to Bowery traditions.

A sharp observer of life in Whitechapel, he was well aware of the weird vogue by which sightseers paid good money to be escorted through the city’s slums and witness “picturesque” sites of local and migrant deprivation. He exported the idea to Chinatown.

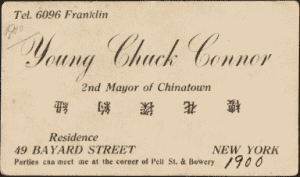

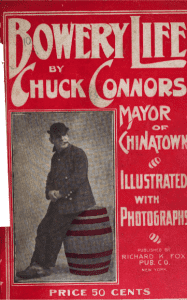

Connors was able to rebuild his life after meeting Richard K. Fox, publisher of the Police Gazette. The latter owned several properties in the district and offered his protégé free accommodation at 6 Doyers Street in exchange for magazine tales about the exploits of “The Great Chuck Connors.” He would enthral New Yorkers with lively stories (in a colorful dialect) about his neighborhood. In 1904 Fox assisted Connors in producing an autobiography Bowery Life where the author is introduced as the “Mayor of Chinatown.” The label stuck.

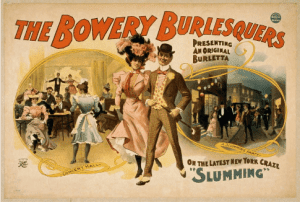

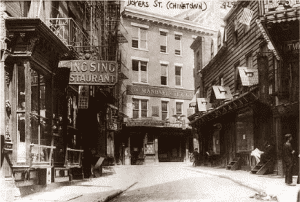

Doyers Street was, according to contemporary guidebooks, a seriously crooked street. Connors exploited that reputation. The Bowery Boy became the Godfather of Manhattan’s slumming industry, a phenomenon that was described in The New York Times (September 1884) with the headline “A Fashionable London Mania Reaches New York.”

One of his favorite stop-overs was The Pelham Café at 12 Pell Street, headquarters of Mike Salter, a Russian-Jewish gangster known as the uncrowned “Prince of Chinatown.” Every single night, his saloon hosted a crowd of visitors who came to hear pianist “Professor” Nicholson play ragtime, accompanied by a seventeen year old waiter named Izzy Baline who belted out raunchy versions of various popular songs. For the young singer this was the start of a glittering career. He would soon change his name to Irving Berlin.

Although he did have macho and no-nonsense competitors in the Bowery, Connors – with the blessing of local tong leaders – made Chinatown his exclusive territory. No other “lobby-gow” (Chinese slang for tour guide) would dare to bring his clients into the district.

Slum Tourism & Stereotyping

Chuck made Barney Flynn’s Saloon the headquarters from where he organized his “vice tours.” He sat his customers down for an “authentic” Chinese dinner; he took them to the Chinese Theatre at 5/7 Doyers Street (with reserved seats for “Americans”). There was the standard introduction to a temple, known in local jargon as a “joss house” (a corruption from the Portuguese Deos for God).

The tour’s climax was a visit to an opium den where his clients encountered the “terror” of drug dependency. It was pure theater. Connors employed Chinese actors to create illusions of addiction and drug-induced stupor.

To add a street element of imminent danger, fights with hatchets and knives between rival gangs were staged whilst in the distance gunfire could be heard. Shocked visitors were neither shot nor robbed in Chinatown. They safely left the area to re-join their respectable families under the impression that they had witnessed a glimpse of “primitive” life in the depraved and seedy margins of society. Slumming had been an adventurous day trip.

Chuck himself became a celebrity host and his tour was a ‘must’ for other prominent figures, including tea magnet Thomas Lipton, novelists Israel Zangwell and Hall Caine, actors Henry Irving and Anna Held. When Chuck Connors died of pneumonia on May 10, 1913, his passing was widely reported. According to the New York Times his funeral was attended by sporting friends, local businessmen, gangsters and Tammany Hall politicians, all paying their respect to the Mayor of Chinatown.

The procession, consisting of sixty three coaches of mourners and another six of floral arrangements, started outside Chuck’s room in Doyers Street. The cortège snaked through Chinatown, stopping for mass at the Catholic Church of the Transfiguration in Mott Street, after which it continued over the new Manhattan Bridge towards Calvary Cemetery in Queens. As the coffin passed by, Chinese merchants set off traditional funeral firework displays, honouring a white man they considered one of their own – and therein lies a painful irony.

Slum tourism consisted of typecast representations that were based on anti-immigration rhetoric and bigoted press reports linking urban deprivation to an ‘alien’ culture of addiction, debauchery and violence. Chuck’s Chinatown was a stage on which white stereotypes about ethnicity and color were either formed or confirmed. It contributed to the racial profiling that Asian-Americans would experience subsequently.

DO YOU LIKE TO GARDEN?

THE RIHS KIOSK NEEDS VOLUNTEER(S) TO MAINTAIN OUR GARDEN. DO YOU HAVE AN HOUR OR TWO A WEEK? DO YOU NEED COMMUNITY SERVICE CREDITS? CONTACT US AND HELP US MAINTAIN OUR WONDERFUL GARDEN

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

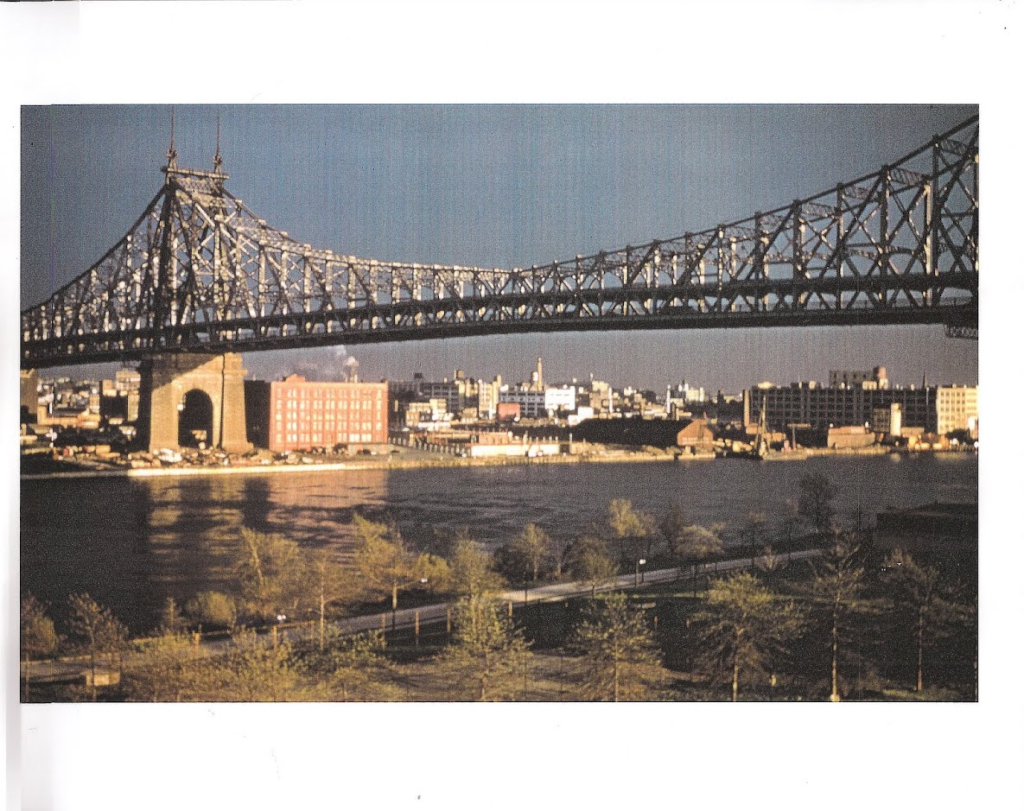

WEEKEND PHOTO

SEND RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

QUEENSBORO BRIDGE SHOWING

NY ARCHITECTURAL TERRA COTTA WORKS ON

VERNON BLVD

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Illustrations, from above: the Edward Mooney House at 18 Bowery on the corner of Pell Street; Chuck Connor’s presentation card, 1900 (Museum of the City of New York); The Bowery Burlesquers presenting a satire on New York’s slumming craze, 1898 (Library of Congress); Chuck Connors’ autobiography; Doyers Street, Chinatown, 1909; Chinese Theatre entrance, 5-7 Doyers Street (date unknown); and Slumming according to Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper (Library of Congress).

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment