Monday, April 24, 2023 – AN EARLY DAREDEVIL WHO HAD MANY SUCCESSES AND THEN…………..

FROM THE ARCHIVES

MONDAY, APRIL 24, 2023

ISSUE 973

Sam Patch: Early American Daredevil

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JACK KELLY

Sam Patch: Early American Daredevil

April 23, 2023 by Jack Kelly

On a chilly November day in 1829, a man dressed completely in white stood before a crowd on the precipice of the High Falls of the Genesee River in the middle of Rochester, New York. Many watching had traveled for days to view the spectacle. All eyes were riveted on one of the most famous men in America.

In our own day, we’ve been fascinated by Philippe Petit walking a wire between the World Trade Center towers, or by Evel Knievel leaping over a row of buses on a motorcycle. A forerunner of these daredevils was Sam Patch.

As a boy, Sam had learned the art of jumping when he leapt for fun from the roof of the six-story stone textile mill where he worked. Slater’s Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, was the first major factory in the nation. Sam turned every jump into a four-act drama: the tense anticipation, the thrilling leap, the heart-stopping disappearance, and the joyful resurrection.

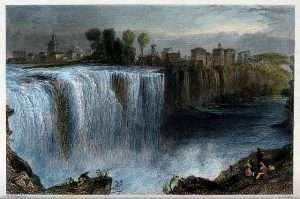

The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 had made Rochester the largest flour-milling city in the world. The town roared with the clattering machinery driven by the river’s water power. The walls of the Genesee gorge formed a misty amphitheater below the falls. On Friday, November 6, a crowd of more than ten thousand people gathered there for the show.

Sam had earlier scouted the river, taking soundings below the falls. Part of his secret was that dropping into the frothy water at the base of a cataract softened the impact of the landing. Now he bowed, said a few words, launched himself, and plummeted. Some cried out, “He’s dead!” After a tense moment, he bobbed to the surface, relieving the onlookers.

Why did he do it? Was it a hunger for attention? A death wish? For Sam Patch, it went beyond the personal. He was reasserting the worth of industrial laborers like himself. Sam had started working twelve-hour days in the mills at the age of eight. He had found little time for play or for schooling. As a factory hand, he was a hireling, dispensable, worth less than the machinery he tended. He worked for someone else’s profit.

Americans did not take easily to factory work. In 1824, workers in Pawtucket walked off the job to protest a decision by mill owners to cut wages by a quarter and extend the work day by an hour. Women and girls instigated the nation’s first industrial strike. Men, including Sam Patch, joined in.

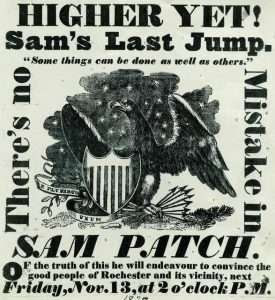

Patch later moved to Paterson, a prosperous mill town in New Jersey. On a whim, he upstaged the opening of a pleasure garden by leaping from the top of the 77-foot Passaic River Falls. In doing so, he defied the city’s upper classes — the place of amusement was off-limits to working people. He jumped again on the Fourth of July, 1828, advertising his feat with the terse phrase that would become his motto: “Some things can be done as well as others.” It was the working man’s sneer at the pretensions of the elite. Sam Patch had found his calling.

By the time he was thirty, Sam was traveling the country, jumping from ships’ masts and over waterfalls. He became the first of the Niagara Falls daredevils, leaping from a platform into the seething cauldron at the bottom of the falls. With this feat, the Buffalo Republican declared, “he may now challenge the universe for a competitor.”

Now, to the consternation of Rochester’s respectable citizens, Sam scheduled another jump in the city a week after the first — on Friday the thirteenth. He had a platform constructed to raise him even farther above the river, 120 feet. “There’s no Mistake in SAM PATCH,” his handbills read. “HIGHER YET! Sam’s Last Jump.”

Again the great mass of spectators assembled. The mills shut down. Watchers crowded windows and roofs. The sensation, one viewer noted, was “between a horse race and an execution.” All waited in the penetrating cold of a gray November afternoon.

Sam Patch wore the white togs that were the uniform of mill workers. He stepped onto the platform. He had imbibed enough whiskey to make him sway a bit as he looked out on all those looking back.

“Napoleon!” he shouted, knowing few could hear. “Napoleon was a great man. But he couldn’t jump the Genesee.” Sam paused. The wind carried his words away over the housetops. “That was left for me to do. I can do it and I will.”

That was his belief. Anyone, even a working man, could be great. Could be somebody. Instead of a cog in a machine. A man could take his life into his own hands. He could dare.

The anticipation had built long enough. Sam stepped to the very edge of the platform. A man in the crowd bit his thumb until it bled. Each spectator drew a breath and held it. Sam looked into all their eyes, into the abyss. He jumped.

He lost control of his erect posture halfway down. His arms flailed. He tipped sideways. Some spectators covered their eyes. Sam Patch slammed into the river.

“When the bubbling water closed over him,” a journalist wrote, “the almost breathless silence and suspense of the multitude for several minutes was indescribably impressive and painful.” No one moved or spoke. Then, finally, “it became too apparent that poor Sam had jumped from life into eternity.”

It wasn’t until the next March that a workman watering horses near the mouth of the river broke the ice and discovered Sam’s frozen body, still dressed in white. Over his grave, someone mounted a wooden plaque that read: “Sam Patch. Such is Fame.”

MONDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

ANSWER WILL BE PUBLISHED THURSDAY

SEND RESPONSE TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

WEEKEND PHOTO

CHAPLAIN AND GUESTS AT THE OPENING

OF COLER IN 1952.

THOM HEYER GOT IT!

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: High Falls of the Genesee River and Sam’s Last Jump handbill.

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2022 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment