Weekend, October 26-27, 2024 – POLITICS FROM THE DAY WE BECAME A REPUBLIC

SATURDAY IS “GOLDEN DAY” TO REGISTER AND VOTE IN THE UPCOMING ELECTION

This Saturday is the last day to register and and vote in the Presidential Election. If you live on Roosevelt Island, stop in our Early Voting Site.

(YOU MUST REGISTER AT YOUR REGULARLY ASSIGNED POLLSITE)

You will be able to register and vote (by affidavit ballot) on Saturday.

Saturday, October 26th is the last day to register and be able to cast a ballot for this election.

See you at Gallery RIVAA, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. Saturday

Other Early voting hours are 8 a.m. to 5 pm. weekends and 8am. to 8 p.m. weekdays.

Early voting ends Sunday. November 3rd.

Related Web Link: WWW.VOTE.NYC

ELECTION 1880 vs ELECTION 2024

LET’S TAKE A LOOK

Weekend, October 26-27, 2024

NEW YORK ALMANACK

ISSUE #1336

What Does The Election of 1800 Have To Do With 2024?

October 24, 2024 by James F. Sefcik

Although historians generally disagree, many people think History does repeat itself. Are there any parallels between the Election of 1800 and the contest for the presidency in 2024?

John Adams and Thomas Jefferson had been debating different viewpoints about the Constitution since they first worked on the Declaration of Independence in 1776. Adams feared giving the people too much control while Jefferson thought the presidency had too much power.

“You are afraid of the one – I, of the Few,” wrote Adams. “You are Apprehensive of Monarchy; I, of Aristocracy.” Both men were concerned about elections: “Elections, my dear Sir, I look at with terror,” Adams contended, who was facing reelection having won the presidency in 1796.

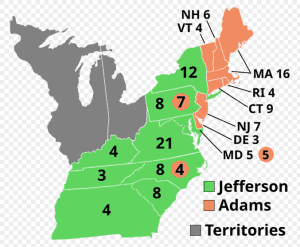

The two founders squared off against each other in 1800. They both received the same number of votes in the Electoral College; under the Constitution of 1787, a tie sent the contest to the House of Representatives for a final decision.

Both men and their supporters elevated the rhetoric. Jefferson warned that “the enemies of our Constitution are preparing a fearful operation.”

The Federalist Alexander Hamilton, though no friend of Adams, argued that Jefferson and his Democratic Republican supporters would “resort to the employment of physical force” to accomplish their ends. Sixty-four year old Adams believed it was necessary to restrain the will of the majority while the younger Jefferson (57) wished to submit to it. He expressed confidence in “the People.”

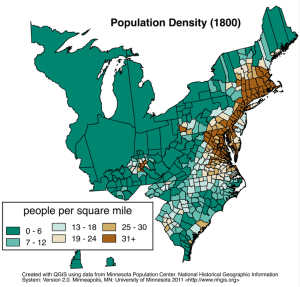

But just who were “the People” in 1800? The first census in 1790 identified 3.9 million American residents, of whom 700,000 were enslaved. Native Americans were also excluded.

But earlier, the Constitutional Convention, in order to prevent the dissolution of the Union as threatened by South Carolina, compromised by declaring that each slave would count as three-fifths of a white person for the purpose of representation in Congress.

So even though the two most populous states, Virginia and Pennsylvania, had a roughly equivalent free population, Virginia had three more seats in the House of Representatives and thus six more voters in the Electoral College.

It was not by happenstance that for 32 of the first 36 years of the American Presidency, the White House was occupied by Virginians, all of whom were slaveholders.

The Founders left it to the states to determine how members of the Electoral College were selected. Since George Washington was unopposed in both 1788 and 1792, that was a non-issue.

By 1796, it was the qualified voters (white property owning males primarily) who chose electors in 7 of the 16 states. In remaining ones, state legislators made the decision.

But the emergence of the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans as nascent political parties, introduced a new element. It was expected that the top vote-getter would become president while the next highest became vice president.

So the results of voting in the Electoral College in 1796 saw John Adams garner 71 votes while Thomas Jefferson came in second with 68 votes. There was no such thing as a ticket at that time.

During his administration, Adams turned dramatically to the Right as evidenced by his support of Britain against France and the enactment of four Alien and Sedition laws, one of which remains in place even today.

Jefferson, along with his compadre James Madison, championed the opposite side of both issues, going so far with the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions wherein they argued that the states had the right to declare laws unconstitutional.

Despite popular opinion, the Constitution does NOT give the Supreme Court the power to address the constitutionality of federal legislation. It was Chief Justice John Marshall that made that determination in 1819. The acrimony of the parties thus made the election of 1800 especially significant.

Jefferson felt that the election would “fix our national character” and “determine whether republicanism or aristocracy would prevail.” Despite his Federalist credentials, Hamilton continued his tirade against Adams writing “Great and intrinsic defects in his character unfit him for the office of chief magistrate,” adding “the unfortunate foibles of a vanity without bounds, and a jealousy capable of discoloring every object,” to complete his attack.

Both sides relied on an expanded print media for their campaigns since it was regarded as demagoguery for candidates to seek office directly. Negative campaigning became the norm.

According to one historian “Republicans attacked Adams for abuses of office, Federalists attacked Jefferson for his slaveholding.” Clergymen also entered the fray, contributing to the argument that voters had the choice between “God – and a religious president” or “Jefferson – and no God.” Others saw the election “between Adams, war and beggary, and Jefferson, peace and competency.”

There was no singular “Election Day’ in 1800. Thus voting occurred between March and November. Nor was there a secret or even a paper ballot. To vote, one had to identify himself as a supporter of one of the parties. Recognizing the potential problem posed by such a practice, 7 of the 16 states enacted new or modified formats even before the election was over.

Finally, the Electoral College, comprised of 138 men, met on December 3rd. John Adams was rebuffed, receiving but 65 votes. But both Jefferson and Aaron Burr, the purported Jeffersonian Republican vice presidential candidate, each received 73 votes, resulting in a tie and throwing the outcome

into the hands of the lame duck Congress, dominated by Federalists.

After 36 ballots taken over several days beginning on February 11, Jefferson emerged as the third president of the United States on February 17, 1801 with the electoral votes from 10 of the 16 states and just 3 weeks before Inauguration Day as prescribed in the Constitution.

In 1804, the Twelfth Amendment was adopted whereby electors are required to cast a distinct vote for each office, eliminating the controversy surrounding the election in 1800.

However, it remains possible for an election, with each candidate having the same number of electoral votes, for the final decision to rest with the House of Representatives.

Thomas Jefferson was inaugurated on March 4, 1801, marking the initial peaceful transfer of power by rival political parties and their leaders in our history.

In his Inaugural Address, he declared “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists,” in an attempt to unite the country. He saw the results as a true revolution, breaking ties with England and instituting major changes within America.

Could a similar scenario occur in 2024? Will History repeat itself?

PHOTO OF THE DAY

NEW HOLIDAY MERCHANDISE

ARRIVING SOON AT THE RIHS VISITOR KIOSK

STAY TUNED AFTER ELECTION DAY FOR DETAILS

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

JUDITH BERDY

We invite you to become a cherished member of our RIHS community. Simply visit our website, RIHS.us, and select the ‘Membership’ option. It’s super easy to join online via PayPal. Your support plays a pivotal role in keeping the RIHS thriving. We appreciate you!

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment