Monday, January 13, 2025 – How grand architecture and design came to New York

John LeFarge:

Eclectic Art Circles

in London and Manhattan

JANUARY13, 2025

ISSUE #1368

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Jaap Harskamp

I am back from vacation and the new Lenovo is making life a breeze.

I can tell you the tale of the week on the high seas later. Did not miss your weather, but mine was never above 75 degrees.

John La Farge: Eclectic Art Circles in London & Manhattan

January 9, 2025 by Jaap Harskamp

During the late nineteenth century articles that focused on artist’s dwelling and studio as a demonstration of his or her creative personality became fashionable reading.

Between March and April 1884, six installments were published simultaneously in London and New York City of “Artists at Home,” a serial publication of twenty-five photogravures (a high quality print process) by Joseph Parkin Mayall with biographical sketches by the art critic and member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Frederic George Stephens (1827-1907).

The London home of Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) in Holland Park with its Arab Hall or Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s Italianate villa in St John’s Wood were presented in great detail and glowing terms. These grandiose mansions created enormous curiosity, both in Britain and America.

Victorians in Togas

Introduced by the great German art critic Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768) in 1763, the term “eclectic” was most clearly defined a decade later by Joshua Reynolds in his Discourses (1774), describing the ancient heritage as a “magazine of common property, always open to the public, whence every man has a right to take what materials he pleases.”

Dutch painter Lawrence (Lourens) Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) was born on January 8, 1836, in Dronrijp, Friesland. Trained at the Antwerp Academy of Art, he was an Orientalist with a preference for Merovingian and Egyptian subjects.

When on honeymoon in the Campania region, he visited Pompeii to witness the first excavations of the site. Inspired by the spectacle, he embarked on depicting scenes from Greek and Roman Antiquity. A prolific artist, he came to be known as the painter of “Victorians in togas.”

In 1864 he secured a commission for twenty-four pictures from Belgian-born dealer and publisher Ernest Gambart (1814-1902) who at the time dominated London’s art market; in 1869 he received a contract for another forty-eight paintings. These works were exhibited at the prestigious French Gallery, Pall Mall. Successful sales linked the painter closer to Britain.

In December 1869, some nine months after the death of his first wife, Lawrence met Laura Epps. Half his age, she made him decide to settle in London with his two young daughters. Having married in July 1871, the couple made Townsend House on Titchfield Terrace near Regent’s Park their home.

Lawrence re-designed the property to resemble a Roman villa, but in the early hours of October 10, 1874, an accident happened. The barge Tilbury was towed westwards along Regent’s Park Canal.

Laden with sugar, nuts, barrels of petroleum and five tons of gunpowder, the canal boat caught fire as it went under Macclesfield Bridge, causing an explosion that killed all on board. The blast seriously damaged Townsend House.

In Alma-Tadema’s elaborate reconstruction of the property each room was given a distinct theme. Downstairs there were a Gothic library, a Japanese studio (for Laura), and a Spanish boudoir. The upstairs parlors were laid out in Moorish and Byzantine styles. Lawrence’s studio was given a Pompeian look.

As soon as the restoration work was finished, the artist went out in search of a new project to mark his position as the arbiter of Victorian taste. He found a villa at 44 Grove End Road in St John’s Wood, once owned by Jacques-Joseph (James) Tissot, a prominent French painter who had returned to Paris in December 1882.

When the family settled there in November 1886, the grand mansion of sixty-six rooms had been modeled in Italianate style. The entrance to the hall was laid with Persian tiles and named the Hall of Panels as it consisted of an “unending” series (some fifty in total) of vertical paintings against the white walls produced by friends and visitors to the house.

One room was filled with treasures from China and Japan. Another chamber had leather-covered walls with cabinets and brasses of Dutch workmanship.

Central to the structure was a balcony overlooking a marble basin with fountain. Alma-Tadema himself occupied a three-story studio with walls of grey-green marble and capped with a semi-circular dome covered in aluminum. One of its stained glass windows was designed by a painter and muralist from New York City.

Gilded Age Architect

Having studied art history in Rome, Vermont-born Richard Morris Hunt (1827-1895) decided on a career in architecture instead. He trained in Geneva, before being admitted to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the very first American architect to enter this prestigious institution. His schooling was thoroughly French.

Back in the United States by 1856, he opened a practice in New York becoming the city’s most prominent architect. He has been labeled the builder who “gilded the Gilded Age.”

Hunt shaped New York’s built environment with his designs for the Metropolitan Museum, the Roosevelt Building, the vanguard Stuyvesant apartment block, the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty, and numerous grand mansions (including Vanderbilt’s estate on Fifth Avenue), although few of his buildings still stand.

His grand structures were based on French neo-classical and Renaissance models. Almost single-handedly, he replaced the dominant English High Victorian public building of the 1860s/70s with his interpretation of French classicism.

His first eye-catching project was the Tenth Street Studio Building. Completed in January 1858, the structure at 51 West 10th Street was New York City’s earliest multiple-artist studio. Boasting twenty-five studios, its central atrium was a shared area that featured a glass ceiling and gas lighting for daylong illumination.

Hunt himself rented space in the building where he founded the first American architectural school in 1858.

An early tenant in the building was William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) who first occupied a small apartment and then took over the gallery originally intended as exhibition space.

To American critics, eclecticism served as a defining characteristic of the artist’s work to indicate his exploration of multiple genres, his stylistic borrowings from Old Masters, and his passion for exotic objects of various historical periods. Chase encouraged his students to adopt a similar approach by instructing them: “Take the best from everything.”

Marquand Mansion

In 1884 Hunt built the Marquand residence at the northwest corner of Madison Avenue & 68th Street. Banker Henry Gurdon Marquand (1819-1902) had made his fortune in financing railroads. Having developed a passion for art, he acquired paintings by Anthony van Dyck, an array of Roman bronzes, and a rich collection of Chinese porcelains.

One of the co-founders of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Marquand acted as its second President and donated many works of art to the institution.

The Marquand mansion was designed to call up memories of a French “château” (castle). The outside looked palatial, but ample attention was given to the building’s interior. Rooms were arranged in a rectangular plan around a central hall from where a double staircase gave access to the tiered galleries above.

Each section was decorated in a different historical style. A Pompeian salon, Moorish library, Japanese drawing room and Spanish refectory were designed to house Marquand’s eclectic collection of art works.

Alma-Tadema’s presence here was almost inevitable. In 1882, Marquand had commissioned a painting from him intended to depict Plato teaching philosophy to a group of followers. After various re-workings of the painting, the artist eventually completed “A Reading from Homer” in 1885.

He would also be involved in the decoration of the estate. His skill as an interior designer was internationally known. Marquand was aware of his talent when he commissioned the artist to design the mansion’s music room.

The Greek-style suite of furniture was planned by Alma-Tadema himself (at the staggering cost of £25,000) and compromised a music cabinet, several settees, chairs, occasional tables and stools.

All items were executed in London’s West End by Messrs Johnstone, Norman & Co. of 67 New Bond Street under the supervision of Norfolk-born William Christmas Codman (1839-1921, who, from 1891 onward, would act as chief silver designer for Gorham Manufacturing Company of Providence, Rhode Island).

Alma-Tadema commissioned Frederic Leighton to create a triptych ceiling painting that featured allegorical figures representing music, dance and poetry. Central to the room was a grand pianoforte, the workings of which had been supplied by Steinway & Sons (now known as the “Alma-Tadema Steinway”).

Edward Poynter, another artist who sought inspiration in classical antiquity, was requested to paint the piano’s fallboard. Its interior lid was fitted with parchment sheets to be signed by its performers (names included Walter Damrosch, Arthur Sullivan, William Gilbert and others).

Backwards & Forwards

John La Farge (1835-1910) was the eldest child in a family of urbane Catholic French immigrants who had settled in New York City. His father, a successful lawyer, was a refugee from the ill-fated expedition by Napoleon Bonaparte to regain control of Saint-Domingue on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola.

Born in 1835, John was brought up with close attention to French culture and educated at Mount Saint Mary’s College, Maryland. He then studied law in New York, without ever abandoning his interest in art.

In 1856 he left for Europe. In Paris he briefly worked at Thomas Couture’s studio and visited museums in northern Europe to copy the Old Masters. When news broke of his father’s illness, he returned to New York City.

On his way back he stopped by in Manchester to see an exhibition that included paintings by the Pre-Raphaelites from which he drew inspiration.

After briefly taking up his studies again, the death of his father left him financially independent. Free from having to pursue a legal career, he dedicated his life to painting and rented a studio in the Tenth Street Studio Building (which he would maintain for the rest of his career).

After meeting Richard Morris Hunt, he traveled to Newport, Rhode Island, to study painting with the architect’s brother, William Morris Hunt.

Having married in 1860, his family life was centered in Rhode Island, but his outlook was that of a cultivated metropolitan artist. During the 1860s he was one of the first American artists to be influenced by Japanese color prints (he visited Japan in 1886 in the company of Henry Adams).

Having embarked on mural painting in the 1870s, he was commissioned by architect Henry Hobson Richardson to paint walls at Trinity Church, Copley Square, in Boston. The project (completed in 1876) established his name as a muralist.

During that same period he began experimenting with stained glass which, at the time, was a relatively new medium to the United States. In Britain, the Gothic Revival had elevated its creation to an art form.

The majority of stained glass used in America was imported and produced in a traditional manner. Having worked out a technique for the manufacture of opalescent glass, La Farge was granted a patent (no. 224,831) for a “Colored-Glass Window.”

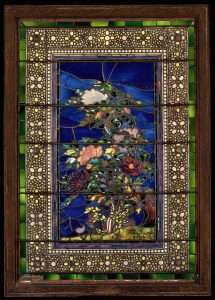

Between 1886 and 1902 he created a series of glass stained windows based on the Japanese theme of “peonies in the wind.” One of those had been commissioned by Alma-Tadema for the decoration of his London studio. Another was acquired by Marquand and installed at his Newport (summer) residence.

It was a meaningful moment when, in October 1912, London auctioneers Hampton & Sons announced the sale of Alma-Tadema’s Grove End property and its contents. Jean Guiffrey, a former curator at the Louvre in Paris acting on behalf of the Boston Museum of Fine Art, acquired the glass stained painting for its return to the United States.

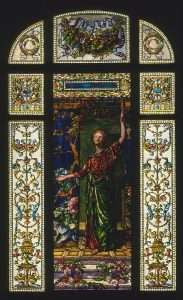

The complexity of La Farge’s workmanship was shown in a window commissioned in 1908 by Mrs George T. Bliss for her house at 9 East 68th Street, Manhattan. The work features a woman in classical garb drawing back a doorway curtain. Tiny pieces of glass were joined together to evoke folds in her gown; panels with garlands and Pompeian ornament frame the work.

This is the paradox: La Farge used ground-breaking techniques in order to create an image that represented the backward looking tradition associated with Alma-Tadema and members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

In the same year that John La Farge began work on the Bliss window, six automobiles representing America, France, Germany and Italy set off from Times Square on a 169-day ordeal competing in a New York City to Paris Race. The contest was won by the American team driving “The Flyer,” a car built in Buffalo, NY, by the E. R. Thomas Motor Company.(You can read more about the race here).

Whilst contemporary artists retreated into the past by seeking inspiration in late medieval or early Renaissance culture, technology’s exponential growth moved ahead and increased the pace of life. Art had to be dragged into the modern world.

While others were shopping for “diamonds & jewels” I was at this wonderful Ardastra sanctuary in Nassau. I was thrilled to meet Rosie’s relative living in the warm Bahamian sunshine.

CREDITS

NEW YORK ALMANACK

Illustrations, from above: W. P. Frith’s “A Private View at the Royal Academy,” 1883; Lawrence Alma-Tadema’s “A Reading from Homer,” 1885 (Philadelphia Museum of Art); Henry Gurdon Marquand’s mansion at the northwest corner of Madison Avenue and 68th Street, built in 1884, demolished ca. 1912; The Alma-Tadema Steinway, 1887 (Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, Massachusetts); John La Farge’s “Peonies Blown in the Wind,” 1886 (Museum of Fine Art, Boston); and John La Farge, Window from the Bliss house at 68th Street, 1908/9. (The Met, New York City).

JUDITH BERDY

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment