Monday, September 16, 2024 – Just up the river is a red arched bridge

10 Secrets

of

Hell Gate Bridge

in

NYC-Part 1

Monday, September 16, 2024

ISSUE # 1308

Untapped New York

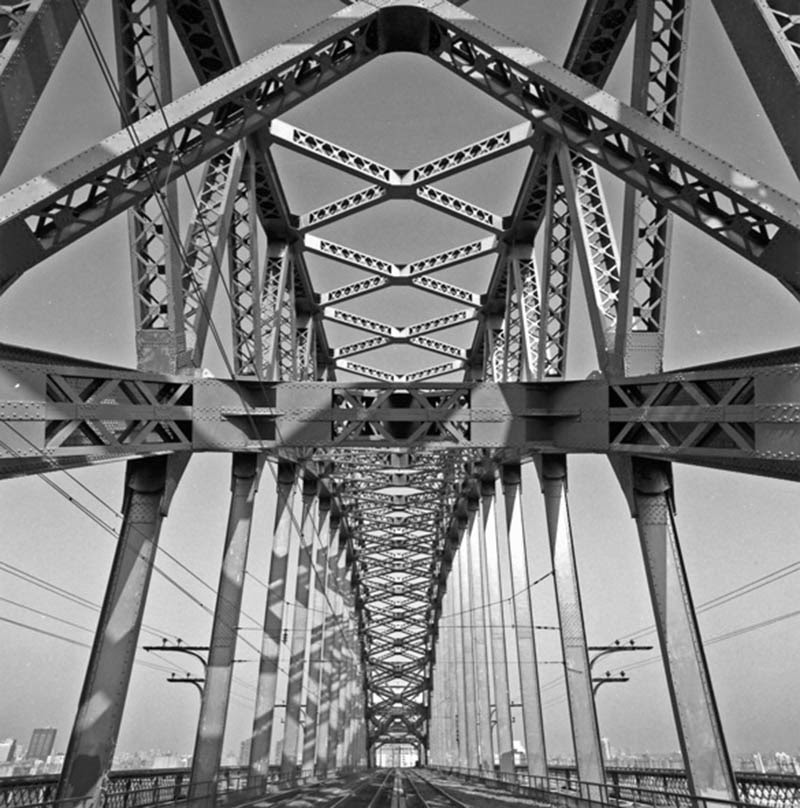

New York City’s Hell Gate Bridge sits on the north end of the East River, between Astoria, Queens, and Randall’s Island. The bridge is named for the once-dangerous channel it crosses, derived from the Dutch word hellegat, which means “hell channel.” Infrastructure aficionados marked the span’s centennial year with cake and events in 2017.

Hell Gate also happens to be a favorite of Dave Frieder, “the Bridge Man” and author of The Magnificent Bridges of New York City. Frieder has been documenting sights from atop the city’s bridges for over two decades. With his help and that of our Chief Experience Officer, Justin Rivers, we bring you ten fun facts and secrets about the Hell Gate Bridge. Want more? Join us for our upcoming Powering NYC: East River Ferry Tour, where you’ll learn more about Hell Gate’s “explosive” past and sail past multiple bridges, abandoned islands, waterfront power plants, and more!

The Hell Gate Bridge is actually a complex of three bridges: the well-known Steel Arch, an inverted bowstring arch that spans a former water-filled channel (Little Hell Gate) between Wards and Randall’s Islands, and a small truss bridge, which would have been a double bascule-type bridge that goes over a small “Kill” between the Bronx and Randall’s Island.

In 2015, a pedestrian and bike route was opened beneath arches of the truss bridge, providing a pleasant and easy way to connect between the Port Morris in the Bronx and Randall’s Island. The bridge was the result of years of activism by groups like South Bronx Unite and others who have been advocating for healthier urban design for a community adversely affected by continued industrial waterfront conversion.

The Queens-side tower of the Hell Gate Bridge sits on solid bedrock, reaching only 15 to 38 feet below ground level. The Wards Island side was a completely different story because it lay near upturned rock strata that made the Hell Gate so treacherous to navigate by water. Also, a gas line that had run under the river prior to the bridge’s construction revealed a fissure in the bedrock which made creating a uniform bridge foundation nearly impossible.

Bridge engineer Gustav Lindenthal’s solution for the Wards Island tower was to utilize fifteen 18-foot diameter caissons to provide solid footing. It took sandhogs (excavation workers) several weeks to dig deep enough to find the reported fissure. It was much deeper than they had originally thought based on initial borings. The solution was one Lindenthal had already used closer to the surface. He used concrete to secure one of the caissons where the fissure passed through its center and, where the fissure lay at a connection point of two other caissons, he bridged the gap with a concrete cantilever. It was the first time this practice was employed in bridge building. In comparison to the Queens tower, the Wards Island tower caissons reach down anywhere from 94 to 123 feet.

The Hell Gate’s “live load” capacity is 24,000-pounds per foot (that is 12 tons per foot), one of the most extreme load capacities for a bridge. In fact, Lindenthal designed the bridge so that sixty 200-ton locomotives could be placed end to end and the structure would easily take the weight.

Yet throughout the bridge’s history, it has never come close to testing that capacity. According to Sharon Reier’s book The Bridges of New York City, on the very day the Hell Gate Bridge opened in April 1917 the future of private rail in the United States was being called into question. A mere two days later the United States declared war on Germany and a year later all rail was nationalized for the war effort. The Pennsylvania Railroad would have a hard time bouncing back from this over the next fifty years. At its height, the PRR ran about 65 trains daily over the bridge. That number plummeted to four after the failure of Penn Central in 1970. Currently, Amtrak runs approximately 40 trains over the bridge.

The “grip” of a bridge rivet (or mechanical fastener) is the thickness of the steel it holds together. The rivets of the Hell Gate Bridge happen to have the longest grip of any bridge in New York City: over nine inches. Due to the high carbon steel it is constructed out of, the span could last well over a thousand years.

Unfortunately that 1000 year guarantee does not include the paint job. By the early 1990’s the steel’s coating was in rough shape. With the urging of Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, the US Congress allocated $55 million to re-paint the bridge for the first time since it was built. The color chosen was a deep red called “Hell Gate Red.” But there was a problem, the clear urethane top coating wasn’t formulated to withstand UV bombardment from the sun. This, in turn, faded the red undercoating which was already fading before the paint job was finished. Amtrak chose to use the same paint in the late 1990’s to patch up the damage but it too began to fade. The bridge has undergone multiple paint jobs since.

Part 2 Tomorrow

Blooms came and went, not a well planned event. It is sad that the great CJ Hendry flower event was poorly planned and went viral.

Only once before did this happen, the great Cherry Blossom crowds. Time for FDR State Park, FDR Four Freedoms Foundation, State Parks, RIOC, PSD and NYPD should better plan for any event in the park. Social media should be considered if the event could attract thousands.

Meanwhile, our neighbors were enjoying great Jazz at the Library garden and our neighbors were

showing their artistic talents painting the panels in Blackwell Park.

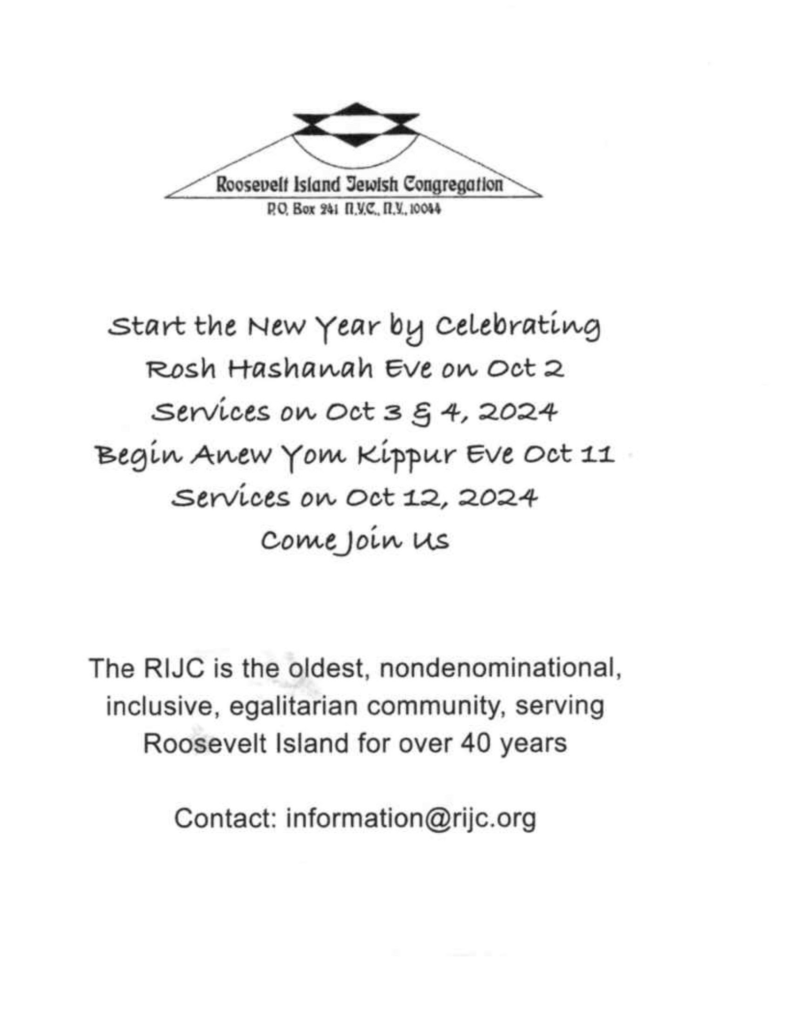

THE HIGH HOLIDAYS

ARE SOON.

CREDITS

JUDITH BERDY

ESTHER COHEN

THE SHOP

Untapped New York

All image are copyrighted (c) Roosevelt Island Historical Society unless otherwise indicated

THIS PUBLICATION FUNDED BY DISCRETIONARY FUNDS FROM CITY COUNCIL MEMBER JULIE MENIN & ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE FUNDS.

Copyright © 2024 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment