Weekend, September 4-5, 2021 – HIS ART WILL CHEER YOU

WEEKEND EDITION

SEPTEMBER 4-5, 2021

OUR 460th EDITION

RED GROOMS

FROM THE SMITHSONIAN AMERICAN ART MUSEUM

MARLBOROUGH GALLERIES

ARTNET

DAYTONIAN IN MANHATTAN

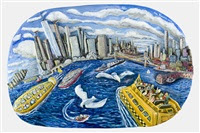

Red Grooms, Blewey II, color offset lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, 1981.173.2

Red Grooms, Marlborough Graphics, Inc., Lorna Doone, 1980, color lithographic diptych with collage and rubber stamp on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Glen D. Nelson, M.D., 1998.57.11, © 1979, Vermillion Editions Limited, Inc. and Red Grooms; Minneapolis, MN

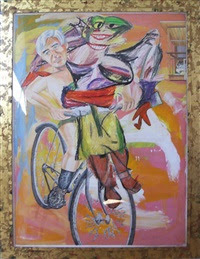

Red Grooms, Gertrude, 1975, color lithograph and collage on paper mounted on paperboard, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Jacob Kainen and museum purchase through a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, 1975.3

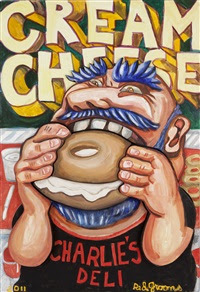

Red Grooms, Aarrrrrrhh, 1971, color lithograph, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Harry W. Zichterman, 1973.

Red Grooms, Sno-Show I, 1991, color lithograph on paper, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Glen D. Nelson, M.D., 1998.57.12, © 1993, Akasha and Red Grooms; Minneapolis, MN

BELOW IMAGES COURTESY MARLBOROUGH GALLERIES

FROM ARTNET:

Red Grooms is an American artist known for his painted-collage sculptures of both fictional and observed scenes. Characterized by his distinctive stylization and humorous portraits of people, Grooms’s works are constructed from illustration board and a hot glue gun, pieced together into a believable physical space. “In the New York works I’ve done I have tried to make it a kind of portraiture thing where I was really trying to get the texture of what I thought I saw, particularly in the neurosis of the population, and present it in context with the props—the mailboxes, fireplugs, any texture of the city,” he has explained. Born Charles Rogers Grooms on June 7, 1937 in Nashville, TN, he went on to study at the Art Institute of Chicago, before moving to New York in 1956. There, Grooms befriended and exhibited with artists such as Alex Katz, Jim Dine, and Claes Oldenburg, gaining recognition for his unique take on Pop Art. In 1986, the award-winning film Red Grooms: Sunflower in a Hothouse was released, documenting the artist’s process and personality. Grooms continues to live and work in New York, NY. Today, his works are held in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, among others.

WEEKEND PHOTO OF THE DAY

DOCKED IN ANABLE BASIN IN

LONG ISLAND CITY IS THE

PRUDENCE FERRY FROM BRISTOL , R.I.JUST IN CASE YOU NEED AN ESCAPE TO A FAR AWAY ISLAND, YOU CAN VIEW THIS SLIGHTLY BEAT-UP FERRY DOCKED ACROSS THE WAY.

FRIDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

HORACE GREELEY IN CITY HALL PARK

ANDY SPARBERG AND ED LITCHER GOT IT!!!!

Born into poverty, the son of an unsuccessful farmer, Horace Greeley began his career in journalist at the age of 15 in 1826 as a printer’s apprentice. He moved to New York City in 1831 and worked for several newspapers, saving his money and in 1840 embarked on a risky proposition–the founding of the New-York Tribune. The one-cent newspaper was four pages–a single sheet folded in the middle. After a long, rocky beginning it was a success.

In stark contrast to its great competitor, James Gordon Bennett’s New York Herald, the Tribune refused to publish stories of scandal and sensational crimes. Greeley lobbied for reform, abolishment of slavery, and an end to political corruption. He served in Congress in 1848-49 and ran for President in 1872 as the Liberal Republican candidate.

Greeley died on November 29, 1872, before Electoral ballots were counted and just a month after his wife May’s death. Harper’s Weekly lamented, “Since the assassination of Mr. Lincoln, the death of no American has been so sincerely deplored as that of Horace Greeley.”

On May 19, 1888 The Evening World reported “The committee of printers interested in the movement to erect a statue to Horace Greeley will meet at 475 Pearl street to-morrow.” The project gained ground quickly and five days later The New York Times wrote, “A well-defined effort is being made by the union printers of this city and Brooklyn and the members of the Horace Greeley Post, Grand Army of the Republic, to erect a statue in honor of Horace Greeley in City Hall Park.”

On May 28 The New York Times advised, “Alexander Doyle, the artist, was selected to submit a design for the statue and it was recommended that the statue represent Mr. Greeley in a sitting posture. It is expected that a model of the statue will be completed in about six weeks.”

The chosen site for the monument was on Printing House Square. The Patterson Sunday Call wrote, “It will stand in City Hall park, just across the way from the magnificent building of The Tribune…Alexander Doyle, the celebrated American sculptor, has the work in hand.” The article said, “The statue will be placed on a granite pedestal of chaste classic design of the severest simplicity.”

The cost of the project was placed at “$15,000, perhaps more,” said the Patterson Sunday Call. (The figure would translate to about $420,000 today.) Newspapers reported on the fund raising and according to The Sun by the fall of 1890 $10,557 had been raised. It was no longer only typesetters and printers contributing to the project. The Horace Greeley Statue Committee published the names of wealthy New Yorkers like Levi P. Morton and Cornelius N. Bliss as they donated funds. James Gordon Bennett, once Greeley’s greatest rival, donated $1,000.

At some point two significant changes were made to the plan. First, the well-known sculptor John Quincy Adams Ward took over the project. Secondly, the location was changed from City Hall Park to directly in front of the Tribune Building.

The unveiling was held at 11:00 on September 20, 1890. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported, “Printing House Square in New York is no longer without a memorial of Horace Greeley, who did more than any other one man to make the spot famous.” Chauncey M. Depew was the “orator of the day,” according to the New-York Tribune. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle said, “After Mr. Depew’s speech Miss Gabrielle Greeley, Horace Greeley’s daughter, pulled the cord, the flags which had enveloped the statue dropped away, the crowd cheered, the band played ‘Yankee Doodle,’ and the ceremonies were over.”

Ward’s design closely followed that of Doyle, which had originally been approved. Greeley was depicted in a sitting position in a heavily-fringed Victorian easy chair. He held a copy of the New-York Tribune loosely over his knee, as if in deep thought. Gabrielle Greeley later recalled that Ward “spent hours studying my father as he worked in his office [and] after his death took a mask of his face.” The polished Quincy granite base was designed by architect Richard Morris Hunt.

In 1915 the Tribune leased the corner, ground floor space in its building to a drugstore. The deal included the remodeling of the storefront and that presented a problem. On June 13 The New York Times explained “An up-to-date American druggist cannot display the latest concoctions of ice cream and fruit flavors with a twenty-foot statue right where a show window ought to be.”

The New-York Tribune was deeply concerned that the statue of its founder be relocated to a proper place. “It is the hope of the officers of The Tribune Association and many others who revere the memory of Mr. Greeley for the great work which he accomplished by his public services that a new site may be found for the statue, as least as near to the scene of Mr. Greeley’s journalistic labors as the City Hall Park,” said an article on September 21, 1915.

No one was more concerned than Gabrielle Greeley, the last of the Greeley family. When a proposal to move the statue to Battery Park was suggested, she responded with an open letter to New Yorkers, published in The Sun on December 24. It said in part, “I do appeal to you not to have my father’s statue buried in an out of the way obscure park…let his statue rest somewhere in Printing House Square, that his feet trod so often in his busy life.” She ended her letter with an emotional plea, “Again, as the work of a great American sculptor, as a remarkable likeness of a characteristic American, let it not pass into obscurity, O people of this city and of his heart.”

The decision was finally made to relocate the statue to the exact spot for which it was originally intended–City Hall Park directly across from the Tribune Building. In 1922 The Evening World romantically mused:

It is only a couple of years since the statue of Horace Greeley was shifted from the barren surroundings of the Tribune doorway to a little green spot in City Hall Park, on the Park Row side near Chambers Street. The trees here now have grown up around the worthy old gentleman and he sits as he liked to in life, amid a leafy bower.

A century later the description applies. The statue of Greeley is considered by many to be among Ward’s best works.

non-credited photographs taken by the author

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

All image are copyrighted (c)

SMITHSONIAN AMERIAN ART MUSEUM

MARLBOROUGH GALLERIES

ARTNET

DAYTONIAN IN MANHATTAN

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment