Friday, February 26, 2021 – THE CENTRAL LIBRARY ALMOST HAD A BEAUX ARTS LOOK

FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 26, 2021

The

297st Edition

THE BUILDING BEFORE THIS

LANDMARK STRUCTURE OF THE

BROOKLYN CENTRAL

LIBRARY

FROM BROWNSTONER

History

May 5, 2011

by Suzanne Spellen (aka Montrose Morris)

Raymond F. Almirall was a Brooklyn architect best known for civic buildings around the city.

At the dawn of the 20th century, Raymond F. Almirall was an up-and-coming Brooklyn architect with a promising future. After his education at the L’ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris, he returned home and began an association with New York City government that led to his design of libraries, hospitals, asylums and public baths.

Almirall had been chosen as a member of an advisory commission in charge of building the Carnegie Libraries. He was also the secretary of the group.

Andrew Carnegie had put aside millions of dollars for the building of libraries in the United States, his native Scotland and other nations. Brooklyn got money to build 21 Carnegie branches, and Almirall designed three of them.

Carnegie money was earmarked for branches only, but the Brooklyn Public Library was in need of a new Central Library, which would be financed by the city. What an opportunity this would be for any architect to design such a lasting public project, and Raymond Almirall was in the catbird’s seat. In 1908, Almirall was chosen to design the new Central Branch.

The Beaux-Arts-led City Beautiful movement was shaping public spaces in America’s cities. What could be more beautiful than Brooklyn’s Grand Army Plaza, already a City Beautiful site, with the Arch, entrance to Prospect Park, the fountains and the new Institute of Arts and Science still growing on Eastern Parkway?

Almirall’s new Central Library would join McKim, Mead & White’s grand museum in Classically inspired glory. It was to be a huge, domed four story structure, complementing the nearby museum.

Almirall plan for new Central Branch, 1907. Photo via Brooklyn Public Library

The new library would have a large central dome and entrance at the apex of the building, with colonnades along both sides, running along both Eastern Parkway and Flatbush Avenue. It would have had the latest accoutrements of library science.

Almirall planned reading rooms, classrooms, music rooms, an auditorium, a children’s library, research and rare book rooms, lunch rooms, miles of stacks, and an underground garage with conveyor belts for transporting books, book elevators, and rooms dedicated to cataloging and restoration and repair.

The new library would also have a first-aid station, a newspaper room, telephone and stenographer’s rooms, and the back sorting rooms would have tracks for carts to run along, for transporting books. The cost was estimated to be $4,500.000.

Ground was broken for the library in 1912. By 1913, the foundation had been dug out, and part of the west wall along Flatbush Avenue had been built. Then the money ran out, and work was halted. It would not begin again for another 30 years, the poster child for incompetence in city building projects.

At a time when Almirall should have been basking in the glow of his magnificent new library rising to join the Institute of Arts and Sciences, he was taking on other projects, designing his final Carnegie Library branch further down Eastern Parkway, at Utica Avenue, and designing churches and Seaview Hospital buildings.

Then, the curse of civic responsibility occurred — jury duty. In 1919, Almirall was impaneled as a grand juror in investigations of city corruption under the administration of Mayor John F. Hylan, who was mayor of NYC between 1918 and 1925.

Hylan, whose nickname was Red Mike, had grown up in Bushwick, and was a train conductor with the Brooklyn Rapid Transit Corporation until he was fired for almost running down his supervisor. He became a lawyer, and in 1918, with the sponsorship of Tammany Hall and William Randolph Hearst, became the dark horse candidate for mayor, and won.

Almirall’s persistence in getting to the bottom of the muck in the Hylan administration made an enemy of Red Mike. Some say that the reason the library project was stopped in its tracks was Hylan’s doing. Others blame the economy, World War I, poor city planning, other political in-fighting and an overblown project. In the end, Almirall would never see his library finished.

After World War I ended, Almirall moved his family back to France, where he stayed till around 1929. During that time he was chosen as one of the architects adding their expertise to the restoration of the Palace of Versailles, damaged during the war. His was a principal role in that restoration, and in gratitude, France made him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor.

While in France, he also designed several other buildings. He came back to the United States and took up residence in Hempstead, Long Island.

By 1929, the year Almirall came back from Paris, the Flatbush wing of the Central Library had crawled to exterior completion, and the project halted again for lack of funds. Then the Great Depression hit.

During the 1930s, the public mindset toward architectural styles had changed. Gone were the Beaux-Art Classical details, the ornate columns and columns. Art Deco, with its flat surfaces, clean lines and ornamental relief was in vogue.

Almirall’s unfinished library stood awkwardly along Flatbush Avenue like a beached ocean liner. The city chose new architects for the project, Alfred Githens and Francis Keally, who kept the Almirall footprint. The foundations had been dug and were sitting there for 30 years.

They kept the walls of the Flatbush wing and tore down everything else, stripping the walls of ornament and detail, and eliminating the fourth floor. They designed a brand new building around what they had retained, and work began on this less expensive Art Deco design in 1938.

WIKIWAND IMAGE

While the library is certainly great in its own right, and a very beautiful and successful building, it must have been a huge slap in the face to Raymond Almirall, who lived to see them tearing down what would have been his finest and most monumental creation.

A year later, after poor health had put him in Lenox Hill Hospital, Chevalier Raymond F. Almirall died at age 69 on May 18, 1939. His funeral mass at the Church of St. Ignatius Loyola on Park Avenue was attended by a delegation of the Institute of Architects and the Society of American Engineers, organizations of which Almirall had been a member.

He left behind his wife, two sons and a daughter. He was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, home to many other great architects and visionaries. He did not live to see the new Central Library open with much fanfare and ceremony on February 1, 1941. One wonders if he would have liked it.

In the 1930s, architects Githens and Keally were commissioned to redesign the building in the Art Deco style, eliminating the expensive ornamentation and the fourth floor. Construction recommenced in 1938, and Almirall’s building on Flatbush Avenue was largely demolished except for the frame, but some of the original facade along the library’s parking lot is still visible. Completed by late 1940, the Central Library opened to the public on February 1, 1941. It was publicly and critically acclaimed at the time.

The second floor of the Central Library opened in 1955, nearly doubling the amount of space available to the public. Occupying over 350,000 square feet (33,000 m2) and employing 300 full-time staff members, the building serves as the administrative headquarters for the Brooklyn Public Library system. Prior to 1941 the Library’s administrative offices were located in the Williamsburgh Savings Bank on Flatbush Avenue.[5]

FRIDAY PHOTOS OF THE DAY

SEND YOUR SUBMISSION TO:

ROOSEVELTISLANDHISTORY@GMAIL.COM

THURSDAY PHOTO OF THE DAY

MANHATTAN PSYCHIATRIC CENTER

WARD’S ISLAND

ANDY SPABERG, SUSAN RODESIS, JAY JACOBSON, VERN HARWOOD, HARA REISER, GLORIA HERMAN, LAURA HUSSEY, ALL GOT IT

A NOTE FROM MITCH ELLINSON

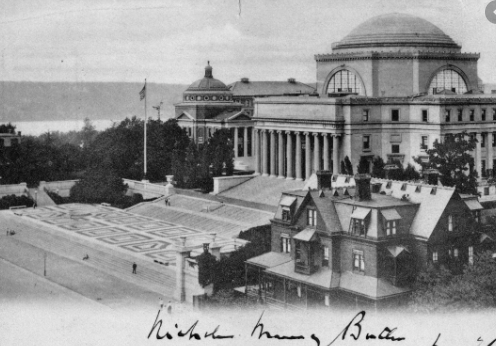

Thanks for your article on the Bloomingdale Asylum. There is just one extant asylum building still on Columbia’s Morningside Heights campus. According to Wikipedia, it was built as a residence for wealthy male inmates. It has had many uses over the years. It is currently the home of La Maison Francaise. Here are some pictures of it to the right of Low Library, the administration building. It was moved and stripped of its veranda when the Columbia campus was built.

Judith Berdy

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Deborah Dorff

Roosevelt Island Historical Society

Sources

BROWNSTONER

WIKIPEDIA

BROOKLYN PUBLIC LIBRARY

FUNDING PROVIDED BY ROOSEVELT ISLAND OPERATING CORPORATION PUBLIC PURPOSE GRANTS CITY COUNCIL REPRESENTATIVE BEN KALLOS DISCRETIONARY FUNDING THRU DYCD

Copyright © 2021 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Leave a comment