May, 2020 Issue of Blackwell’s Almanac now available

Click on the image to read the full newsletter.

May

5

May

4

The New Colossus

Emma Lazarus – 1849-1887 •

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand A mighty woman with a torch,

whose flame Is the imprisoned lightning,

and her name Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand Glows world-wide welcome;

her mild eyes command The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she With silent lips.

“Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless

tempest-tost to me, I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

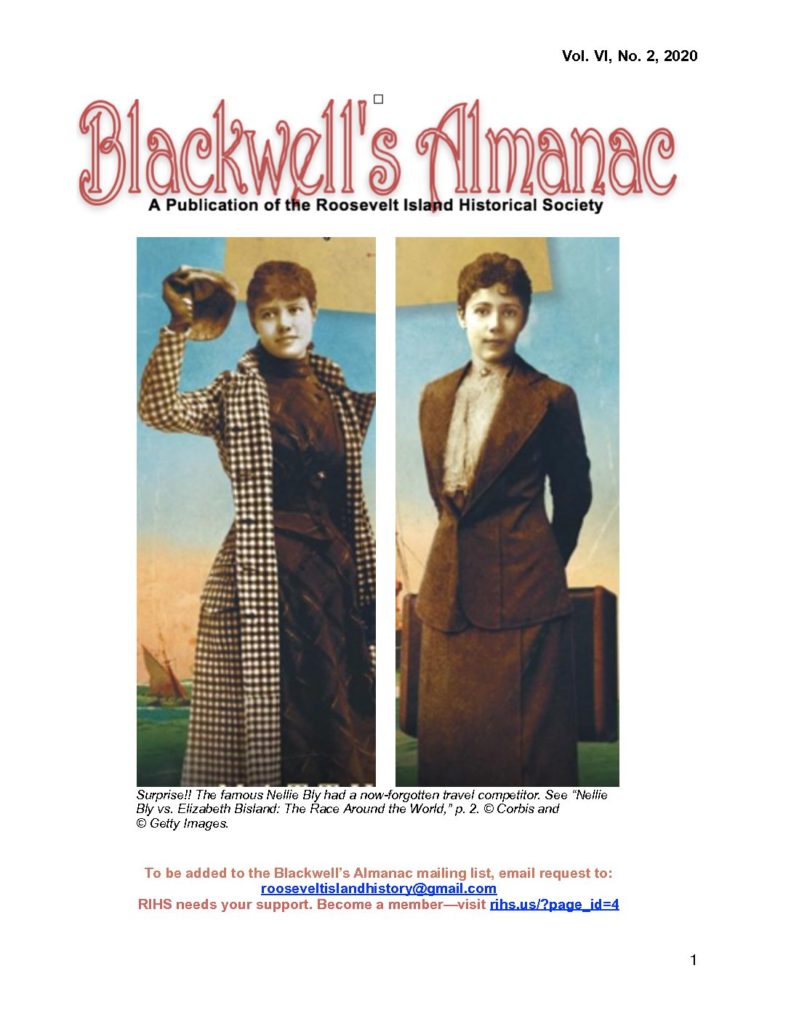

From 1794 to 1890 (pre-immigration station period), Ellis Island played a mostly uneventful but still important military role in United States history. When the British occupied New York City during the duration of the Revolutionary War, its large and powerful naval fleet was able to sail unimpeded directly into New York Harbor.

Therefore, it was deemed critical by the United States Government that a series of coastal fortifications in New York Harbor be constructed just prior to the War of 1812. After much legal haggling over ownership of the island, the Federal government purchased Ellis Island from New York State in 1808.

Ellis Island was approved as a site for fortifications and on it was constructed a parapet for three tiers of circular guns, making the island part of the new harbor defense system that included Castle Clinton at the Battery, Castle Williams on Governor’s Island, Fort Wood on Bedloe’s Island and two earthworks forts at the entrance to New York Harbor at the Verrazano Narrows.

The fort at Ellis Island was named Fort Gibson in honor of a brave officer killed during the War of 1812.

Prior to 1890, the individual states (rather than the Federal government) regulated immigration into the United States. Castle Garden in the Battery (originally known as Castle Clinton) served as the New York State immigration station from 1855 to 1890 and approximately eight million immigrants, mostly from Northern and Western Europe, passed through its doors.

These early immigrants came from nations such as England, Ireland, Germany and the Scandinavian countries and constituted the first large wave of immigrants that settled and populated the United States. Throughout the 1800s and intensifying in the latter half of the 19th century, ensuing political instability, restrictive religious laws and deteriorating economic conditions in Europe began to fuel the largest mass human migration in the history of the world. It soon became apparent that Castle Garden was ill-equipped and unprepared to handle the growing numbers of immigrants arriving yearly.

Unfortunately, compounding the problems of the small facility were the corruption and incompetence found to be commonplace at Castle Garden. The Federal government intervened and constructed a new Federally-operated immigration station on Ellis Island.

While the new immigration station on Ellis Island was under construction, the Barge Office at the Battery was used for the processing of immigrants. The new structure on Ellis Island, built of “Georgia pine” opened on January 1, 1892.

Annie Moore, a teenaged Irish girl, accompanied by her two brothers, entered history and a new country as she was the very first immigrant to be processed at Ellis Island. Over the next 62 years, more than 12 million were to follow through this port of entry.

While there were many reasons to immigrate to America, no reason could be found for what would occur only five years after the Ellis Island Immigration Station opened. During the early morning hours of June 15, 1897, a fire on Ellis Island burned the immigration station completely to the ground.

Although no lives were lost, many years of Federal and State immigration records dating back to 1855 burned along with the pine buildings that failed to protect them.

The United States Treasury quickly ordered the immigration facility be replaced under one very important condition: all future structures built on Ellis Island had to be fireproof. On December 17, 1900, the new Main Building was opened and 2,251 immigrants were received that day.

While most immigrants entered the United States through New York Harbor (the most popular destination of steamship companies), others sailed into many ports such as Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, San Francisco, Savannah, Miami, and New Orleans.

The great steamship companies like White Star, Red Star, Cunard and Hamburg-America played a significant role in the history of Ellis Island and immigration in general. First and second class passengers who arrived in New York Harbor were not required to undergo the inspection process at Ellis Island. Instead, these passengers underwent a cursory inspection aboard ship, the theory being that if a person could afford to purchase a first or second class ticket, they were less likely to become a public charge in America due to medical or legal reasons.

The Federal government felt that these more affluent passengers would not end up in institutions, hospitals or become a burden to the state. However, first and second class passengers were sent to Ellis Island for further inspection if they were sick or had legal problems.

This scenario was far different for “steerage” or third class passengers. These immigrants traveled in crowded and often unsanitary conditions near the bottom of steamships with few amenities, often spending up to two weeks seasick in their bunks during rough Atlantic Ocean crossings. Upon arrival in New York City, ships would dock at the Hudson or East River piers. First and second class passengers would disembark, pass through Customs at the piers and were free to enter the United States. The steerage and third class passengers were transported from the pier by ferry or barge to Ellis Island where everyone would undergo a medical and legal inspection.

If the immigrant’s papers were in order and they were in reasonably good health, the Ellis Island inspection process would last approximately three to five hours. The inspections took place in the Registry Room (or Great Hall), where doctors would briefly scan every immigrant for obvious physical ailments. Doctors at Ellis Island soon became very adept at conducting these “six second physicals.”

By 1916, it was said that a doctor could identify numerous medical conditions (ranging from anemia to goiters to varicose veins) just by glancing at an immigrant. The ship’s manifest log, that had been filled out back at the port of embarkation, contained the immigrant’s name and his/her answers to twenty-nine questions. This document was used by the legal inspectors at Ellis Island to cross-examine the immigrant during the legal (or primary) inspection.

The two agencies responsible for processing immigrants at Ellis Island were the United States Public Health Service and the Bureau of Immigration (later known as the Immigration and Naturalization Service – INS). Despite the island’s reputation as an “Island of Tears”, the vast majority of immigrants were treated courteously and respectfully, and were free to begin their new lives in America after only a few short hours on Ellis Island.

Only two percent of the arriving immigrants were excluded from entry. The two main reasons why an immigrant would be excluded were if a doctor diagnosed that the immigrant had a contagious disease that would endanger the public health or if a legal inspector thought the immigrant was likely to become a public charge or an illegal contract laborer.

From the very beginning of the mass migration that spanned the years 1880 to 1924, an increasingly vociferous group of politicians and nativists demanded increased restrictions on immigration. Laws and regulations such as the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Alien Contract Labor Law and the institution of a literacy test barely stemmed this flood tide of new immigrants. Actually, the death knell for Ellis Island, as a major entry point for new immigrants, began to toll in 1921. It reached a crescendo between 1921 with the passage of the Quota Laws and 1924 with the passage of the National Origins Act.

These restrictions were based upon a percentage system according to the number of ethnic groups already living in the United States as per the 1890 and 1910 Census. It was an attempt to preserve the ethnic flavor of the “old immigrants”, those earlier settlers primarily from Northern and Western Europe. The perception existed that the newly arriving immigrants mostly from Southern and Eastern Europe were somehow inferior to those who arrived earlier.

After World War I, the United States began to emerge as a potential world power. United States embassies were established in countries all over the world, and prospective immigrants now applied for their visas at American consulates in their countries of origin. The necessary paperwork was completed at the consulate and a medical inspection was also conducted there. After 1924, the only people who were detained at Ellis Island were those who had problems with their paperwork, as well as war refugees and displaced persons. Ellis Island still remained open for many years and served a multitude of purposes.

During World War II, enemy merchant seamen were detained in the baggage and dormitory building. The United States Coast Guard also trained about 60,000 servicemen there. In November of 1954, the last detainee, a Norwegian merchant seaman named Arne Peterssen, was released, and Ellis Island officially closed.

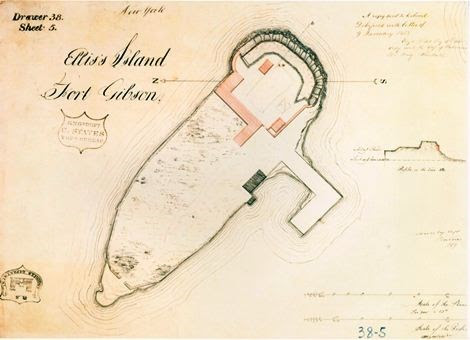

In 1995 I was contacted by a staff member at Ellis Island. In exchange for information on Roosevelt Island he offered a friend and myself tour of the “other” south side of the island. In 1995, the hospital part of the island was not open to the public and was in hazardous condition, wanting me more to see it.

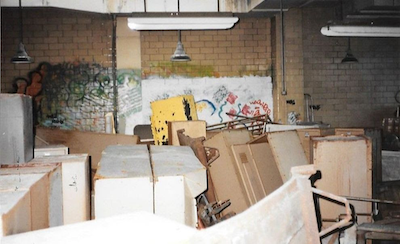

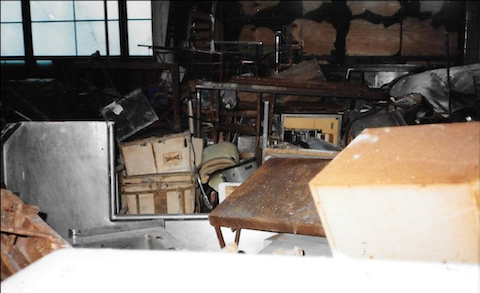

I remember it was a freezing cold day and we walked thru the enormous kitchen in the main building.

Text by Judith Berdy

Photos (c) RIHS

There was a row of kettles for soups and in the corner a Hobart mixer (making bread dough). The kitchen was vast and in abandoned state.

We walked in a long corridor with windows on each side, past the ferry landing and onto the other part of the island. Th weeds and broken glass with wind blowing was an interesting experience.

The hospital at Ellis has a fascinating history, which we did not have space for in this issue. The glass enclosed corridors we walked thru lead to the hospital where persons were treated and most released to become Americans.

Thanks to the STATUE OF LIBERTY ELLIS ISLAND FOUNDATION (c) for the historical information.

There are hat tours of the abandoned buildings and reservations are available online.

Ellis, like Blackwell’s had a community of staff that lived and worked on the island. Their story soon.

Best wishes,

Judith Berdy

212 688 4836

jbird134@aol.com

From Bonnie Waldman about our weekend Coney Island issue:

I have so many great memories of Steeplechase Park. I went there a couple of times each summer from the late 1940’s and all through the 50’s. I rode the Electric Horses with my older brother and rode the parachute with him as well as the Wonder Wheel. I would scream so loud when the car suddenly swung back and forth. One time I “burned” my back going down the giant curved wooden slide. it was REALLY high. I was wearing a midriff so much of my back was exposed to the wood and because I was leaning back instead of sitting up I came off the ride in pain. My mother brought me to the Infirmary that was hidden away off to the side of all the amusements. The nurse put a thick salve on the affected areas. But what I remember most was a midget man clown resting on one of the tables and me wondering what was hurting him. Judy, thanks for jogging my memories of my old Brooklyn.

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

May

2

Coney Island, one of New York’s oldest and finest tourist attractions, wasn’t built in a day. There were many reasons why this place was built, how it was built, and the consequences of the build. And they’re all very fascinating. When you vision Coney Island, you probably vision the amusement park. Coney Island is not only an amusement park, but a large neighborhood filled with many residents. Some of the extremely famous attractions of Coney Island can even be seen from a mile away, like the Parachute Jump and the Wonder Wheel. And up close, they’re even better. The ride is about to begin, so fasten your safety harness.

This is how Coney Island came to be.

Where it All Began Coney Island was an actual island back then. Coney Island’s got a rich history. Development began in the 1840s, when Coney Island wasn’t even connected to the mainland. That’s why it’s called Coney Island, despite not being an actual island. Looking on Google Maps, one can see the Coney Island creek, which gets cut off at Shell Road, and ends there. That’s because the creek used to be a river which flowed into Sheepshead Bay, but through the process of landfill (not where garbage is kept, but the process of filling in land), Coney Island was connected to the rest of Brooklyn, and was no longer an island.

When the first buildings were built on Coney Island, people who wanted to keep the island as a natural park were outraged. In the early 1900s, the city wanted to demolish all buildings south of Surf Avenue, the main avenue that runs through Coney Island, even to this day. The city took this shot, which was part of the Coney Island rebuilding process. The island still had potential, and the city knew it–they didn’t want to throw that potential away.

As mentioned, Coney Island was later connected to the mainland of Brooklyn by a process called land reclamation, or landfill. This process basically connects land to each other by creating new land from river or lake beds. The new land is called reclamation ground. In the 1920s, the city zoned the land so the land north of the boardwalk and south of Surf Avenue would be used for amusement purposes only. This was a settlement the people agreed with.

Three Parks in One Park That’s a lotta people.

During World War II, Coney Island was the largest amusement park in the country, attracting millions of visitors every year, as seen above. At its most successful time, Coney Island actually contained three amusement parks: Luna Park, Steeplechase Park, and Dreamland. Coney Island was soaring at this point. Steeplechase Park was the first of the three, built in 1862 by George C. Tilyou, whose family ran a restaurant in Coney Island.

When he visited the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, he observed the Ferris Wheel, which was introduced at that World’s Fair, and decided to build his own in Coney Island. Once it was built, it immediately became the island’s biggest attraction. He added other rides as well, such as a mechanical horse race course called the Steeplechase. This is actually where the park derived its name from, and is the origin of the name of a current horse-themed rollercoaster in Coney Island, which exists where the original ride once was.

Steeplechase was the western-most park, located where the present-day MCU Park baseball stadium is. Steeplechase was also the park which lasted the longest, because unlike the other two, it made enough money to thrive. Tilyou and his family were able to update the park gradually due to its success, so new rides, such as the Parachute Jump, which exists today, opened on its grounds.

Luna Park was the second park built in Coney Island, built in 1903. The park was built atop the ground of Sea Lion Park, the first permanent amusement park in North America, which was run by Paul Boyton. Luna Park was located on the north side of Surf Avenue, on a site between West 8th and 12th Streets, and Neptune Avenue. The park was created by Elmer “Skip” Dundy and Frederick Thompson. Thompson and Dundy leased empty plots from Tilyou, and used these land plots to build Luna Park.

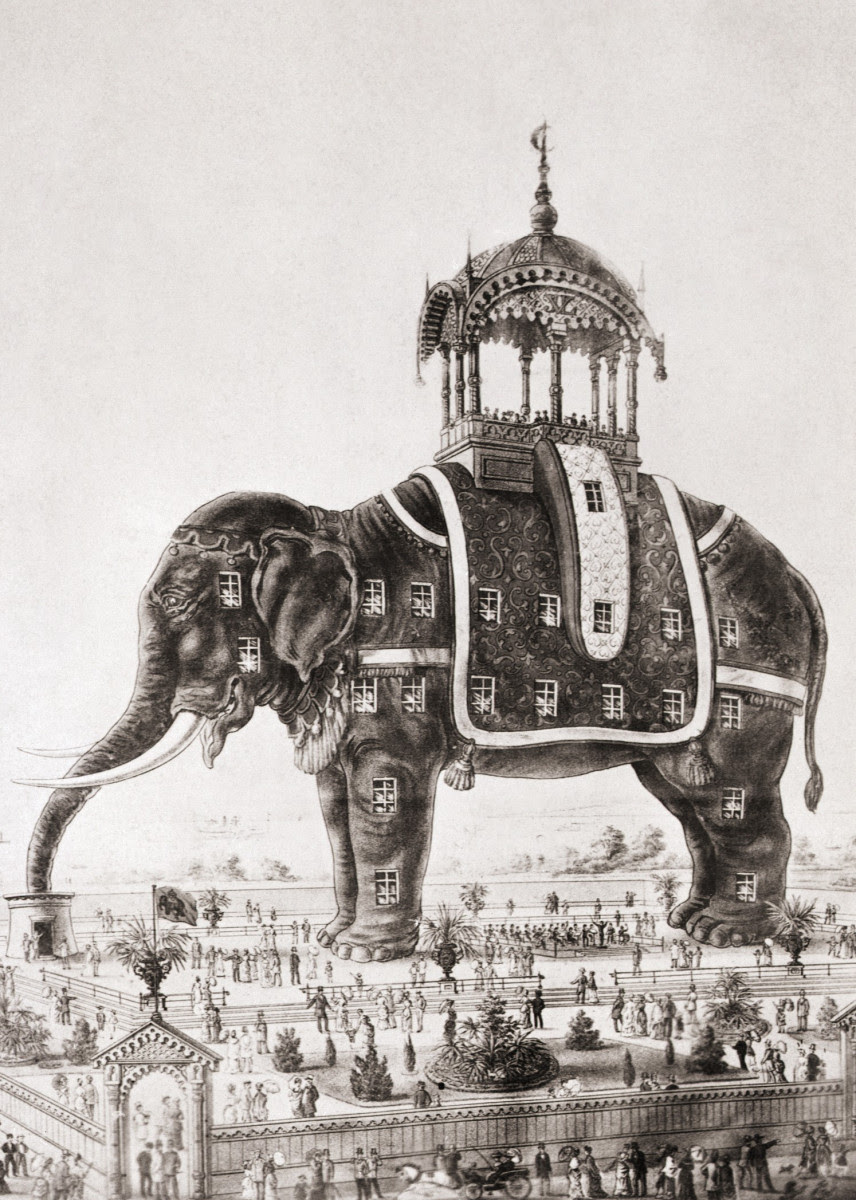

The old Elephantine Colossus, which Luna Park was later built over. The land leased was where the Elephantine Colossus, a seven-story tall tourist attraction built in the shape of an elephant, once stood. Unfortunately, in 1896, it caught fire and collapsed, killing many.

After the destruction of this attraction, the land was available for new use, and Dundy and Thompson purchased the land to build Luna Park on top of. The park thrived for a while.

The last park built was called Dreamland, and it was the largest, most luxurious, and “the grandest” of the three. It was built in 1904 by then-state senator William H. Reynolds. This park was built because Reynolds wanted to challenge Luna Park by making it much more elegant and upper-class, rather than Luna Park, which was noisy, chaotic, and often looked at as ‘low-class’. In order to build Dreamland, you could say he played a bit dirty: he had other people bid on the property for him in order to hide his true means of building an amusement park there. Once Reynolds won the bid, he used his political power to seize control of West 8th Street, which ran through the middle of the area. And so, Dreamland was built. With these three parks, Coney Island thrived. It thrived more than the city and its citizens ever thought it would.

Originally intended to serve as a tourist attraction, the elephant contained novelty stalls, a gallery, a grand hall, and a museum in what would be the elephant’s left lung. The elephant’s eyes contained telescopes and acted as an observatory for visitors. Its manager claimed to see, from the elephant’s back, Yellowstone Park, Rio de Janeiro, and Paris.[4] As Coney Island became more established as a center of tourism and leisure, the elephant began to serve as a brothel as well.[5][6][7] When the elephant caught fire on September 27, 1896, it had not been used for several years.

During this time, many hospitals could not afford incubators to babies who needed it, but for some reason, Dreamland had a supply of them, so premature babies were kept there. Following the fire, news reports claimed that all the babies had died in the fire, but soon after, these reports were corrected, saying that no babies were killed. Most of the babies were saved by Sergeant Frederick Klinck of the NYPD, who made many trips into the burning Dreamland to rescue the babies.

The Wonder Wheel and AstroTower

(now demolished) seen in 2013. As we know, Coney Island is home to some very iconic attractions, that were famous both back in the day and today. Take the Cyclone roller coaster for example. The Coney Island Cyclone was and still is in use today. It is a historic wooden roller coaster that opened on June 18, 1927. It was completely renovated and reopened to the crowds on July 1, 1975. Since then, AstroLand Park invested millions of dollars to regularly update the Cyclone. After AstroLand closed in 2008, the president of Cyclone Coasters, Carol Hill Albert, continued to operate it under an agreement with the city, saving it from permanent closure and demolition. In 2011, Luna Park took over operation of the Cyclone. The Cyclone was declared a New York City landmark in July 12, 1988, and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 26, 1991.

is a 250 foot tall amusement ride, originally located in Steeplechase Park. The Parachute Jump was actually originally built for the 1939 New York World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows, Queens. It was moved to where it is today, then became part of Steeplechase Park in 1941. It is the only portion of Steeplechase Park still standing today. The ride officially closed in 1964 when Steeplechase Park closed, and today it’s no longer in use, but you can still visit it and snap some cool pictures. Fun fact: the Parachute Jump can be seen getting destroyed in the blockbuster film Spider-Man: Homecoming.

Deno’s Wonder Wheel is a 150 foot tall eccentric Ferris wheel located in the heart of Coney Island. It is actually an eccentric wheel, which are different from regular Ferris wheels because, if you ever visit the wheel and take notice, most of the passenger cars slide on rails between the hub and the rim as the wheel rotates. This is a factor that makes the Wonder Wheel so iconic. If you want to hop aboard the Wonder Wheel, but don’t want to deal with the car you’re in sliding back and forth 150 feet up in the air, you can hop in the white cars, which ride the edges and do not move, like a typical Ferris wheel.

Below is a personal note from Judith Berdy

What a wonderful way to spend a day that is gloomy, thinking of a Nathan’s hot dog at Coney Island.

Hope you enjoy your trip to Brooklyn!

Judy Berdy

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Apr

30

The Staten Island Quarantine War was a series of attacks on the New York Marine Hospital in Staten Island—known as “the Quarantine” and at that time the largest quarantine facility in the United States—on September 1 and 2, 1858.

The attacks, perpetrated mainly by residents of Staten Island, which had not yet joined New York City, were a result of longstanding local opposition to several quarantine facilities on the island’s East Shore. During the attacks, arsonists set a large fire that completely destroyed the hospital compound.

At trial, the leaders of the attack successfully argued that they had destroyed the Quarantine in self-defense. Though there were no deaths as a direct result of the attacks, the conflict serves as an important historical case study of the use of quarantines as a first response.

From 1795 to 1798, yellow fever killed thousands in New York City. In reaction, the New York City Common Council passed a quarantine law in 1799 authored by Richard Bayley, the port’s first health officer.[ This act funded the creation of the New York Marine Hospital, and the first patients arrived in 1800. Bayley died from yellow fever while caring for patients there in 1801. The Quarantine had capacity to house 1,500 patients. At its peak in the 1840s, the Quarantine treated more than 8,000 patients each year.

By the 1850s a rigorous inspection system was in place. Newly arrived ships were boarded, and if any signs of disease were found, all passengers were unloaded at the Quarantine. Health officials housed first-class passengers in St. Nicholas Hospital while passengers from steerage were put in the shanties.

The Quarantine was on a large site in the former town of Castleton, overlooking Upper New York Bay near the border of today’s St. George and Tompkinsville. The site is now occupied by the Staten Island Coast Guard Station and the National Lighthouse Museum The Quarantine comprised over a dozen buildings: Map of the Marine Hospital grounds St. Nicholas Hospital, the most-prominent structure on the site; the Smallpox Hospital, with six wards; the Female Hospital, a two-story structure; grounds buildings containing offices, harbor inspectors, and physicians’ residences; eight wooden shanties for housing patients. A six-foot-high brick wall enclosed the grounds.

The Quarantine Hospital, 1858 Opposition to the Quarantine by local residents began from its creation. In this sense, “the quarantine war” could be understood as a decades-long campaign by Staten Islanders against the facility. Land owners opposed the acquisition of the site by the city but also complained about the effects of the Quarantine on property values. “I have thought the existence of the Quarantine very injurious,” explained one land developer in 1849, “to the rise and sale of property “

Staten Islanders blamed local infectious outbreaks on the presence of the Quarantine. In addition, tensions between employees of the Quarantine and local residents grew throughout the 1850s. Attempt to establish a new quarantine facility at Seguine Point In 1857 New York City officials attempted to defuse local anger by moving the facility to a more remote location on Staten Island, Seguine Point.

However, arsonists from the town of Westfield destroyed the construction site before the new facility could be finished.[One participant in that attack wrote an anonymous letter to The New York Times, signed as “An Oysterman”, warning of further action if construction resumed: “Yes, I may say that every urchin who can rub a match will aid in producing a general conflagration of materials that shall be sent there for the purpose of erecting an institution which will endanger their lives and destroy their homes.”[

Another writer to The New York Times declared that the populace would resist the establishment of a quarantine hospital at Seguine Point even if it cost “thousands of lives”. In April 1858, arsonists destroyed the remaining buildings at Seguine Point. A combined reward of $3,000 (equivalent to $89,000 in 2019) from New York State and City officials for information about the perpetrators resulted in only one arrest.[

In 1856 the Castleton Board of Health (located on Staten Island and sympathetic to its residents) passed an ordinance that prohibited anyone from passing from the grounds of the Quarantine into the town. From 1856 through 1858, local residents sporadically erected barricades to prevent access to the Quarantine.[

Yellow fever returned to Staten Island in August 1858. Locals were quick to blame the outbreak on workers from the Quarantine. In August 1858 the Castleton Board of Health passed ordinances encouraging local residents to take action against the Quarantine. When New York City officials sought an injunction against the Castleton Board of Health, locals responded by threatening to burn down the Quarantine. In retaliation, the City shut down the Staten Island Ferry, ostensibly on health grounds. At this point, locals began to stockpile hay and other flammable materials

On September 1, 1858, the Castleton Board of Health passed the following resolution: “[The Quarantine is] a pest and a nuisance of the most odious character, bringing death and desolation to the very doors of the people….Resolved: That this board recommend the citizens of this county to protect themselves by abating this abominable nuisance without delay.”

Attack on the Quarantine Establishment, September 1, 1858 Attack on the Quarantine Establishment, September 1, 1858 Locals acted quickly following the passage of the Castleton Board of Health resolution. At dark, two large groups assaulted the Quarantine: one broke down the gate, the other scaled the wall on the opposite side of the compound. The attackers removed patients from buildings and then systematically used mattresses and hay to set every building on fire.]

The New York Times reported that the conflagration illuminated the bay and the entire east side of Staten Island. Efforts by employees or firemen to combat the blazes were met by violence; one stevedore was shot.[One of the leaders of the attackers, Ray Tompkins (a grandson of former Governor Daniel D. Tompkins) convinced the crowd to spare the medical staff from physical violence. In addition, Tompkins struck a deal with Quarantine staff to leave the Female Hospital standing in exchange for the release of attackers who had earlier been apprehended by Quarantine officials.

The attackers also battered down large sections of the wall surrounding the Quarantine.Two men died in the night, one from yellow fever, and one Quarantine staff member who was murdered by a co-worker. New York City officials were slow to react both because of the health risk posed by sending police officers into a quarantine zone and the likelihood of violence. The following day a handbill appeared posted throughout Tompkinsville.

The handbill read: A meeting of the Citizens of Richmond County, will be held at Nautilus Hall, Tompkinsville, this evening, September 2 at 7 1-2 o’clock , for the purpose of making arrangments to celebrate the burning of the shanties and hospitals at the Quarantine ground last evening, and to transact such business as may come before the meeting. September 2nd, 1858. Several hundred individuals attended the meeting and then proceeded to the Quarantine. The crowd burned down the Female Hospital and the piers.Government response, aftermath, and trial One hundred police officers sent by New York City arrived on September 3. They were heavily armed and even possessed an artillery piece.

The police and hospital staff moved several dozen patients who had been sheltering under makeshift tarps to Ward Island. In addition, Governor John A. King dispatched military units to Tompkinsville.[16] These forces initially consisted of several regiments of New York State militia from the 71st New York Infantry and the 7th New York Militia. The police arrested several leaders of the attack, including Ray Tompkins, on September 4.[18] At trial, the defendants argued that they had destroyed the Quarantine in self-defense. The presiding judge agreed. He noted that patients had been removed and that the local health board had previously identified the facility as a danger to the community. “For these reasons,” he concluded, “I am of opinion that no crime has been committed, that the act, the necessity of which all must deplore, was yet a necessity not caused by any act or omission of those upon whom it was imposed, and that his summary act of self-protection, justified by that necessity and therefore by law, was resorted to only after every other proper resource was exhausted.”

The historian of the conflict Kathryn Stephenson notes that the judge owned property within a mile of the Quarantine and had asked the state legislature in 1849 to remove it from Staten Island. The military occupation of Staten Island ended in early January 1859, when the new Governor of New York, Edwin D. Morgan, cancelled the orders of four companies of the 7th New York Militia which had been sent as a relief force for units that were departing Staten Island.

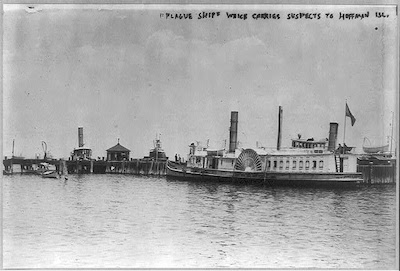

[Quarantine facilities were not re-established on the site. Instead, a floating hospital was used beginning in 1859. Two artificial islands, Swinburne Island and Hoffman Island, began operation as quarantine facilities in the 1860s.[

Hoffman Island is an 11-acre (4.5 ha) artificial island in the Lower New York Bay, off the South Beach of Staten Island, New York City. A smaller, 4-acre (1.6 ha) artificial island, Swinburne Island, lies immediately to the south.

Created in 1873 upon the Orchard Shoal[3] by the addition of landfill, the island is named for former New York City mayor (1866–1868) and New York Governor (1869–1871) John Thompson Hoffman.

During the late 1800s and early 1900s, Hoffman (and Swinburne) Island was used as a quarantine station, housing immigrants who, upon their arrival at the immigrant inspection station at nearby Ellis Island, presented with symptoms of contagious disease(s).World War II

Starting in 1938 and extending through World War II, the United States Merchant Marine used Hoffman and Swinburne Islands as a training station. The Quonset huts built during this period are no longer evident on Hoffman Island, but as of 2017 their remnants remain on Swinburne Island.

During World War II the islands also served as anchorages for Antisubmarine Nets intended to protect New York Bay and its associated shipping/naval activities from enemy submarines entering from the Atlantic Ocean.Post–World War II

When I had decided to do this article I had heard of the unwelcome behavior of Staten Islanders to the facility. Reading about is is shocking. Tomorrow I will travel (by internet) to Governor’s Island. I do not know what I will find

I may add Ellis Island Coney Island and who knows what other islands in the future. Okay, I should add Bermuda, St. Thomas and Martinique!!! (I will resist Devil’s Island, since I do not speak French).

This is issue #40 and there are still more subjects to cover. That does not mean I want this quarantine to go on too long!!

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Apr

28

Native Americans called Wards Island Tenkenas which translated to “Wild Lands” or “uninhabited place”whereas Randalls Island was called Minnehanonck. The islands were acquired by Wouter Van Twiller, Director General of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, in July 1637. The island’s first European names were Great Barent Island (Wards) and Little Barent Island (Randalls) after a Danish cowherd named Barent Jansen Blom.[9] Both islands’ names changed several times. At times Randalls was known as “Buchanan’s Island” and “Great Barn Island”, both of which were likely corruptions of Great Barent Island.

Captain John Montresor, an engineer with the British army, purchased Randalls Island in 1772. He renamed it Montresor’s Island and lived on it with his wife until the Revolutionary War forced him to deploy. During the Revolutionary War, both islands hosted military posts for the British military. The British used his island to launch amphibious attacks on Manhattan, and Montresor’s house there was burned in 1777.

He resigned his commission and returned to England in 1778, but retained ownership of the island until the British evacuated the city in 1783 and it was confiscated. Both islands gained their current names from new owners after the war. In November 1784, Jonathan Randell (or Randel) bought Randalls Island, while Jaspar Ward and Bartholomew Ward, sons of judge Stephen Ward, bought Wards. Nineteenth century The New York House of Refuge youth detention center in 1855. Although a small population had lived on Wards since as early as the 17th century, the Ward brothers developed the island more heavily by building a cotton mill and in 1807 building the first bridge to cross the East River.

The wooden drawbridge connected the island with Manhattan at 114th Street, and was paid for by Bartholomew Ward and Philip Milledolar. The bridge lasted until 1821, when it was destroyed in a storm. After the destruction of the bridge, Wards island was largely abandoned until 1840. Jonathan Randel’s heirs sold Randalls to the city in 1835 for $60,000. In the mid-19th century, both Randalls and Wards Islands, like nearby Blackwell’s Island, became home to a variety of social facilities.

Randalls housed an orphanage, poor house, burial ground for the poor, “idiot” asylum, homeopathic hospital and rest home for Civil War veterans, and was also site of the New York House of Refuge, a reform school completed in 1854 for juvenile delinquents or juveniles adjudicated as vagrants. Between 1840 and 1930, Wards island was used for: Burial of hundreds of thousands of bodies relocated from the Madison Square and Bryant Park graveyards

The State Emigrant Refuge, a hospital for sick and destitute immigrants, opened in 1847, the biggest hospital complex in the world during the 1850s The New York City Asylum for the Insane, opened around 1863 Manhattan Psychiatric Center (incorporating the Asylum for the Insane), operated by New York State when it took over the immigration and asylum buildings in 1899. With 4,400 patients, it was the largest psychiatric institution in the world. The 1920 census notes that the hospital had a total of 6,045 patients. It later became the Manhattan Psychiatric Center.

(c) Wikipedia

Looking east from the footbridge at the mouth of the waterway toward the Triborough Bridge viaduct, 2008 Little Hell Gate was originally a natural waterway separating Randalls Island and Wards Island. The east end of Little Hell Gate opened into the Hell Gate passage of the East River, opposite Astoria, Queens. The west end of Little Hell Gate met the Harlem River across from East 116th Street, Manhattan.

At the Hell Gate Bridge, Little Hell Gate was over 1000 feet (300 m) wide. Currents were swift.

After the Triborough Bridge opened in 1936, it spurred the conversion of both islands to parkland. Soon thereafter, the city began filling in most of the passage between the two islands, in order to expand and connect the two parks. The inlet was filled in by the 1960s.

What is now called “Little Hell Gate Inlet” is the western end of what used to be Little Hell Gate, however, few traces of the eastern end of Little Hell Gate still remain: an indentation in the shoreline on the East River side indicates the former east entrance to that waterway. Today, parkland and part of the New York City Fire Department Academy (see below) occupy that area.

(c) Wikipedia

“Exterior View of the New Inebriate Asylum, Ward’s Island” Image Source: National Library of Medicine

In the late nineteenth century the belief that alcoholism could be cured by confinement led to the establishment of inebriate asylums. In 1864 judges were granted the power to commit alcoholics to asylums.

In the Textbook of Temperance (1869), Lees proclaims, “At last physiologists and statesmen have begun to acknowledge that the drinker’s appetite is a true mania and must be treated as such. Hence the establishment of ‘Inebriate Asylums’ in various parts of the States.” The Asylum on Ward’s Island was opened in 1868 by the Commissioners of Public Charities and Correction, becoming the third in New York State. In New York and its Institutions, 1609-1871 (1872), Richmond chronicles its opening,

“On the 21st of July 1868 the Asylum was formally opened to the public with appropriate services and on the 31st of December the resident physician reported 339 admissions. During 1869 1,490 were received and during 1870 1,270 more were admitted.” While most patients were transferred from the Workhouse, there were also three classes of paying patients, with voluntary attendance of some.

However, the Commissioners and the Attending Physician of the Inebriate Asylum came to agree with prevailing expert opinion that stricter confinement was necessary. Richmond explains, “The rules of the Institution were at first exceedingly mild. The patients were relieved from all irksome restraints, paroles very liberally granted and every inmate supposed intent on reformation. But this excessive kindness was subject to such continual abuse that to save the Institution from utter demoralization a stricter discipline was very properly introduced

As forcible detention came to lose favor as a means of treating alcoholism, the Inebriate Asylum closed in 1875. The buil.” ding temporarily housed the overflow of patients from the Insane Asylum, also located on Ward’s Island, before becoming the Homeopathic Hospital the same year.

The Homeopathic Hospital was renamed Metropolitan Hospital in 1894 when it moved to Blackwell’s Island, marking the beginning of Metropolitan’s affiliation with New York Homeopathic Medical College (now New York Medical College). 5

I could not include all the material in today’s edition. The history that I discovered would only touch the tip of the institutional histories here. The best published source we have is Frederick Dearborn’s book “The Metropolitan Hospital: Chronicle of Sixty-two Years. Dearborn was a physician collector and wrote of the good, bad and adventures of the Homeopathic Hospital on Ward’s Island from 1875 to 1895 and after the hospital moved to Blackwell’s Island in 1895. He led the medical team that went to Mars Sur Alliers in France during World War I representing Metropolitan Hospital. This book is of great value for researchers. It includes the names of Physicians Alumni and even the nursing school graduates until the year 1936. I have often used this book to see if I can locate a graduate.

These two islands have a long and complicated history of institutional uses and buildings being used by multiple hospitals, asylums, orphanage and other facilities. I must say that the history of most of these was bleak and miserable for the patients, inmates or others confined here.

Judith Berdy

212-688-4836

917-744-3721

jbird134@aol.com

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries

Copyright © 2020 Roosevelt Island Historical Society, All rights reserved.Our mailing address is:

rooseveltislandhistory@gmail.com

Apr

27

Both North Brother Island and South Brother Island were claimed by the Dutch West India Company in 1614 and were originally named “De Gesellen”, translated as “the companions” in English.

The islands were both originally part of Queens County. On June 8, 1881, North Brother Island was transferred to what was then part of New York County (later to become the Bronx). On April 16, 1964, South Brother Island was also transferred to the Bronx.

The islands had been incorporated into Long Island City in 1870, before the consolidation of New York City in 1898. North Brother Island The northern of the islands was uninhabited until 1885, when Riverside Hospital moved there from Blackwell’s Island (now known as Roosevelt Island). Riverside Hospital was founded in the 1850s as the Smallpox Hospital to treat and isolate victims of that disease. Its mission eventually expanded to other quarantinable diseases.

The last such facility to be established on the island was the Tuberculosis Pavilion, which opened in 1943. The Pavilion was rendered obsolete within the decade due to the increasing availability, acceptance, and use of the tuberculosis vaccine after 1945.

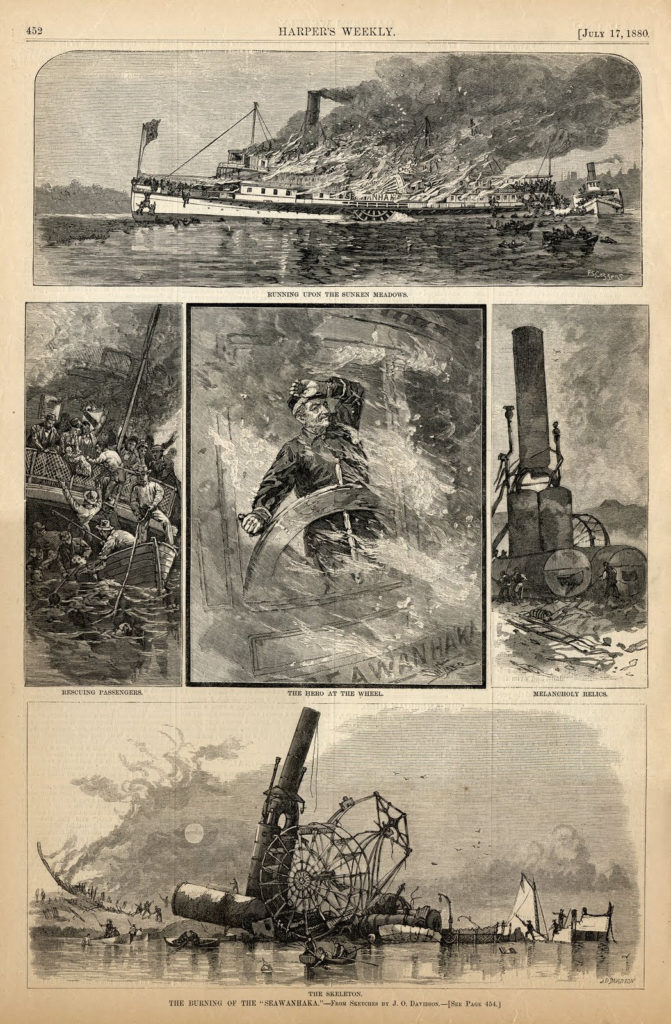

The island was the site of the wreck of the General Slocum, a steamship that burned on June 15, 1904. Over 1,000 people died either from the fire onboard the ship, or from drowning before the ship beached on the island’s shores.

According to Joseph Mitchell, a reporter for newspapers and for The New Yorker, the island was the site of many outings of “The Honorable John McSorley Pickle, Beefsteak, Baseball Nine, and Chowder Club” organized by John McSorley of McSorley’s Old Ale House; photos of the outings are featured on the walls of the bar.

Mary Mallon, also known as Typhoid Mary, was confined to the island for over two decades until she died there in 1938. The hospital closed shortly thereafter. Following World War II, the island housed war veterans who were students at local colleges and their families. After the nationwide housing shortage abated, the island was again abandoned until the 1950s, when a center opened to treat adolescent drug addicts.

The facility claimed it was the first to offer treatment, rehabilitation, and education facilities to young drug offenders. Heroin addicts were confined to this facility and locked in a room until they were clean. Many of them believed they were being held against their will. Staff corruption and cost forced the facility to close in 1963. The facility is said to have been the inspiration for the Broadway play Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie?, which helped to launch the career of Al Pacino.

Since the mid-1960s, New York City mayors have considered a variety of uses for the island. John Lindsay, for instance, proposed to sell it, and Ed Koch thought it could be converted into housing for the homeless. The city also considered using it as an extension of the jail at Rikers Island.

Now serving as a sanctuary for herons and other wading shorebirds, the island is presently abandoned and off-limits to the public. Most of the original hospitals’ buildings still stand, but are heavily deteriorated and in danger of collapse, and a dense forest conceals the ruined hospital buildings.

Wikipedia(c)

Aerial View of island with lighthouse in forefront and buildings of Riverside Hospital to the left

Neat and tidy view from above. Only 20 acres of land, 1/7th the size of Blackwell’s Island

Closeup of Hospital Buddings..Riverside Hospital was originally housed in our former Smallpox Hospital

The lighthouse at the southern tip is no longer visible from the river.

Passengers boarding the General Slocum. Carrying over 1,000 mostly women and children, it caught fire at Hell Gate, north or Blackwell’s Island and finally ran aground on North Brother Island. The island is off the coast of 135 Street in the Bronx. The patients and staff worked to rescue passengers while many died and their remains were brought to the island. It was the worst single day tragedy until 9/11.

Many walked away with minor sentences the story of the General Slocum was lost to history for many years. The passengers were working class women and children from the Lower East Side German immigrant community.

Due to extensive and persistent tracing by a public health physician Mary Mallon was confined to North Brother Island in Quarantine twice. After being discharged the first time she went back to cooking an infecting others. This time she was sent to the Island permanently.

Rendering of the Tuberculosis Hospital which was designed by Isadore Rosenfield, the architect of Goldwater Hospital on Welfare Island.

Rounded design to deflect germs and large open rooms were common beliefs in the treatment of Tuberculosis.

When I chose to write about North Brother Island I remembered that I had copy of an article from Cosmopolitan Magazine about the island. No, not the current Cosmo, but a literary journal of 1892.

On-line I found this reprint of it from a university library via Google.

The story by the famous photographer Jacob Riis is a tender recounting of those who are taken to this island for care and treatment.

Most survive and leave the island, treated by staff who live there their entire careers.

I got a e-mail the the other day from Guy Ludwig, who is encamped in the wilds of Vermont for the duration. He tells of his early visit sneaking onto the not yet completed island.

It is a dreary day and even Beano the cat has no interest in stirring.

I got an artwork from my friend Henry yesterday for my birthday.

Judith Berdy

212-688-4836

917-744-3721

jbird134@aol.com

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

Apr

25

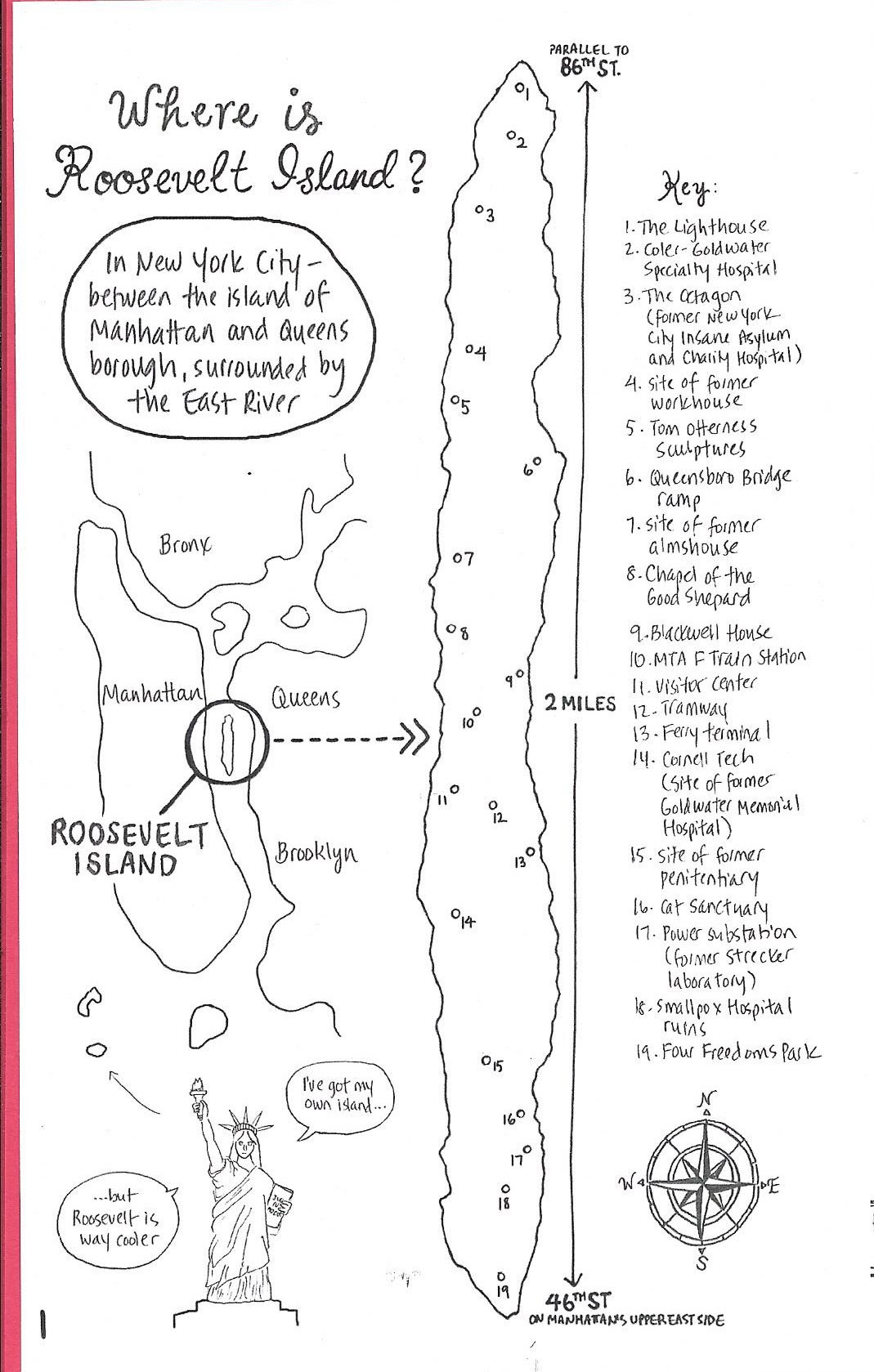

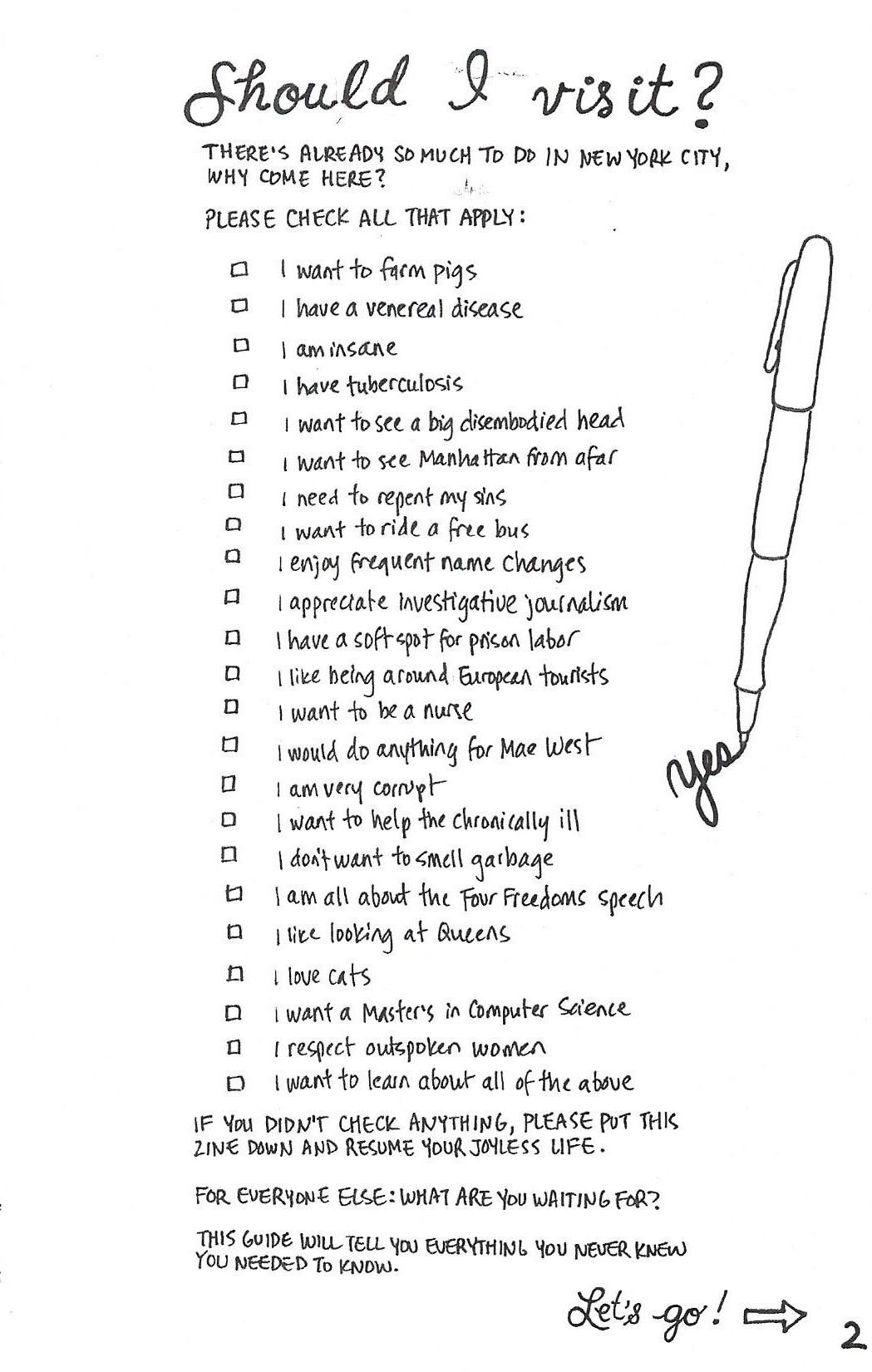

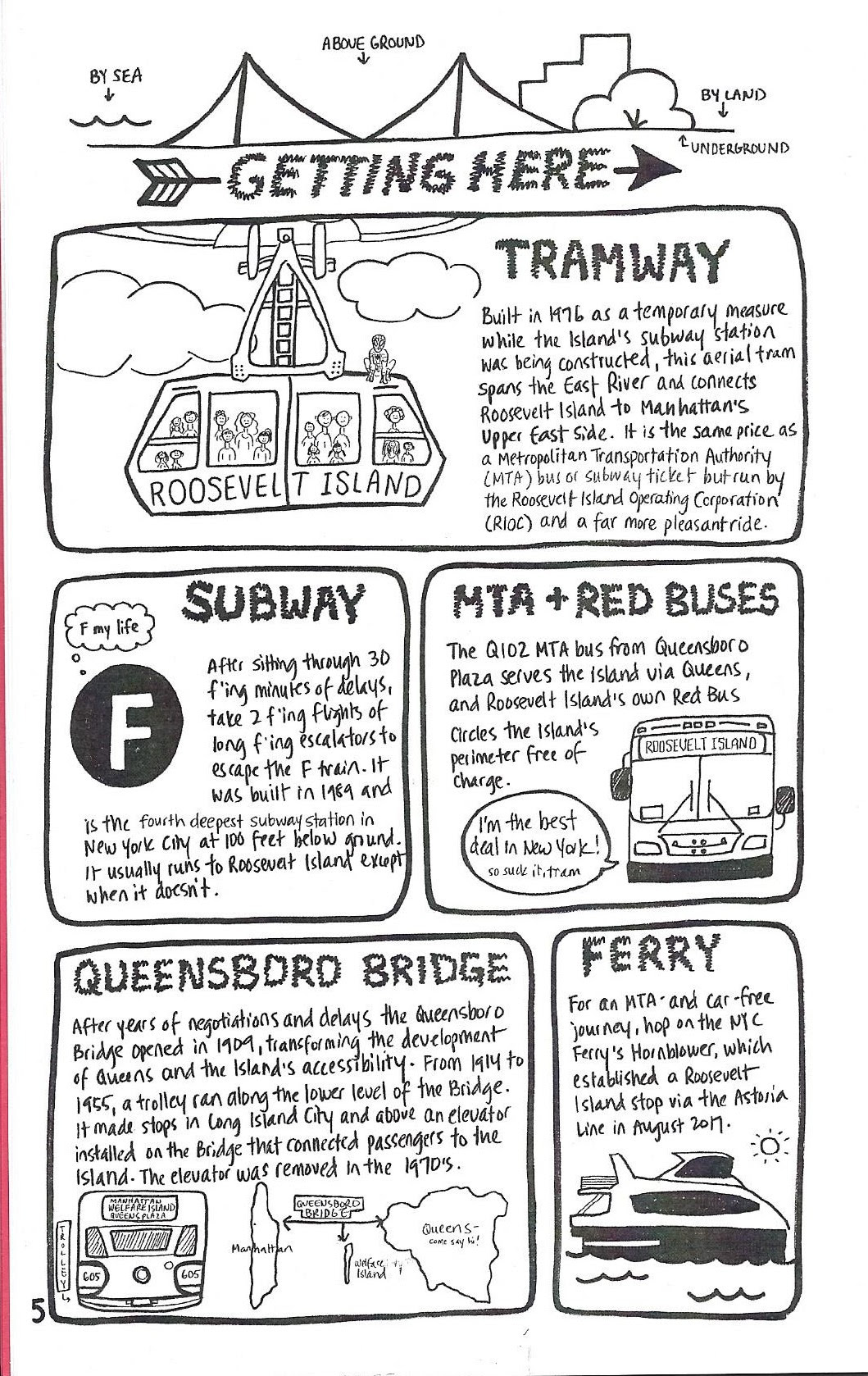

This weekend we are treating you to a special book on Roosevelt Island and its history. Written by Mandy Choi, who worked in the Admissions Office at Cornell Tech, it is a lighthearted look at the history and characters of the island!

Please respect the Copyright of this publication (c) Mandy Choi 2018 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

One of the pages in this booklet is entitled Rx Prescription

Come to Blackwell’s island! We treat ’em all;

Never did I expect to add a 21st century pandemic chapter to our history books.

It is supposed to be sunny tomorrow, time to enjoy the cherry trees before the ground is carpeted in pink petals that float thru the air.

Maybe the clutter around my desk will flutter away into the right files!

Enjoy your weekend

Judith Berdy

212 688 4836

917 744 3721

jbird134@aol.com

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

Apr

24

This is a light look at the interesting structures and sites along Vernon Blvd and the neighborhood opposite the island. It is not meant to be a thorough guide book. I suggest checking on-line at The AIA Guide to New York City, NYC Parks Department, NYPL Digital Images, Friends of Terra Cotta, Google Images, Wikipedia and Google.

Please respect the (c) copyrights of these publications.

Restoration was recently completed on this landmark building that was the office for the Terra Cotta works that was on the site overlooking the river.

The waterfront site was recently cleaned of pollutants and the future of the waterside area has not been revealed. A great view of the site is from the NYCFerry.

The view look familiar? A most popular site for films, TV shows and advertisements. Last summer it was the site of a carnival for the Big Red Dog Movie. Four baseball diamonds are awaiting the summer season! And a beautiful restored sea wall.

No, it’s not the Adams Family home. This was the famous granite castle built by John Bodine (1818-1887), a wealthy wholesale grocer. It was built in 1853, only 200 feet from the East River. Bodine ran for mayor of Long Island City — unsuccessfully — in 1876, but was made one of the first trustees of the Long Island City Savings Bank.

After the death of his wife in 1879 he lost interest in the home and rented it to Harold Larsen of the Long Island Paint Works. After Bodine’s death his son sold it to Young and Metzer’s paper bag company in 1893. Early in the 20th century it was bought by William Youngs and Brothers, who turned the property into a lumberyard and mill, using the house for offices. William Youngs (1892-1978) had a successful lumber operation as LIC was growing into an industrial city. Youngs never lived in LIC.

By the 1950s when the building boom ended he merged with another lumberyard and the firm became stronger as the Youngs-Esdorn Lumber Co. By 1962, an expanding Con Edison made him an offer he could not refuse.

In 1966 the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which usually doesn’t save anything outside Manhattan, sided with Con Edison that the castle was not valuable for landmark status. It was quietly demolished on May 11, 1966 without media attention or protests. Today the site is part of a high-tension switching station.

Photographed in 1937

House was located on 27th Avenue

From Changing New York by Berenice Abbott:

“This Astoria House was built circa 1850 for Josiah Blackwell a New York Dry goods merchant and descendant of Robert Blackwell who settled Blackwell’s Island.(now Roosevelt Island) in the seventeenth century. The house remained in the Blackwell family until 1921, when it was sold and converted to a boarding house with the addition of a fire escape. The young couple relaxes in beach chairs presents a distinctly modern rendition of bucolic contentment. Today the site is occupied by six story apartment building , adjacent to the much larger Astoria Houses , a public housing project built between 1944 and 1951.”

(c) Berenice Abbott

A War of 1812 coastal fort established in 1814 at Hallett’s Point, Queens County, New York. Named Fort Stevens after General Ebenezer Stevens. Abandoned as a fortification at the end of the war in 1815. Fort Stevens and the Mill Rock Blockhouse History of Fort Stevens Established in 1814 during the War of 1812 at Hallett’s Point guarding Hell Gate and the channels of the East River. Fort Stevens was an extensive work with stone walls enclosing a battery with 12 pieces of heavy artillery and a barracks.

This fortification was at the waters edge and vulnerable to landing parties. The fort was protected from the rear by a large stone tower known as Halletts Point Tower on Lawrence Hill commanding a wide section of land and water. The drawing above was probably as viewed from that tower. On the water side, in front of Fort Stevens, was a very strong blockhouse and battery on Mill Rock (a small island in front of the fort).

Other fortifications ringed this stretch of water, a fort at Horn’s Hook and redoubts at Rhinelander Point and the mouth of Harlem Creek. Some of these locations were also fortified during the Revolutionary War. This fortification was one of a line running diagonally across the northern end of Manhattan Island from Fort Laight in the north to the Halletts Point Tower in the south. Included in the line from north to south were Fort Laight, NYC Blockhouse No. 3, NYC Blockhouse No. 2, NYC Blockhouse No. 1, Fort Fish, Fort Clinton (4), Mill Rock Fort, Fort Stevens (5) and the Halletts Point Tower.

These fortifications were located on line of bluffs in the north that overlooked the landside approaches and the major roads into New York City. The southern end of the line guarded McGowans Pass along the Old Post Road and the back door water approach to New York City via a treacherous stretch of water known as Hell Gate. New York City Fortifications 1814 (click twice for full resolution) In addition to these major fortifications, a number of gun batteries and smaller redoubts were located at strategic points to reinforce and protect specific areas. Often these fortifications were connected by earth works and trenches.

EDITORIAL

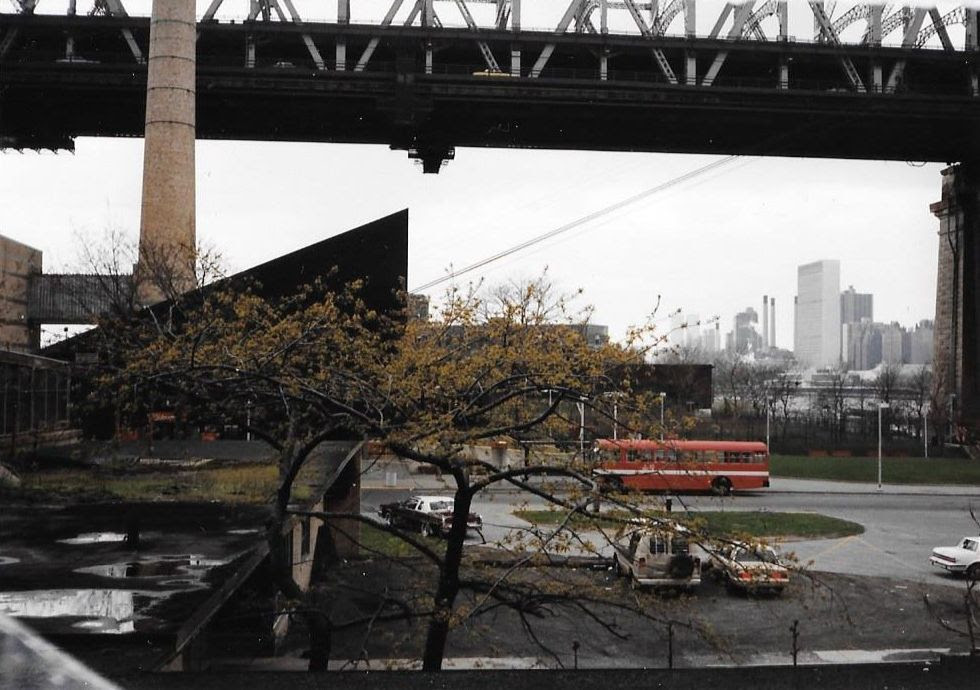

Yesterday, it was Manhattan, today it is Queens. It is easy to look out my window at the power plant. Queensbridge Park and the bridge. When I moved to this apartment in 2005 all that there was to see was the Citicorp building. Now, I only see half of it. Seems some other building just rose in front of it overnight.

Queens was farmland until the bridge opened in 1909. When it opened farmers would bring their produce and foods to a giant market under the bridge. There were fresh food markets under most of our bridges in the early 20th century.

Vernon Blvd. was the capital of stone-cutting. I assume that ships carrying stone could dock alongside the plants. There are still stone and marble cutting operations along the boulevard. For a while in the 1980’s there was a stone cutting company that was cutting granite for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine. I remember visiting the plant and watching giant diamond stone wheel slowly working its way thru the stone. The operation is gone. They gave up on “finishing” the cathedral.

I did not write about other sites along Vernon Blvd. If you have a question, e-mail me.

Judith Berdy

212 688 4836

917 744 3721

jbrid134@aol.com

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Deborah Dorff

Apr

22

A Vanished Building

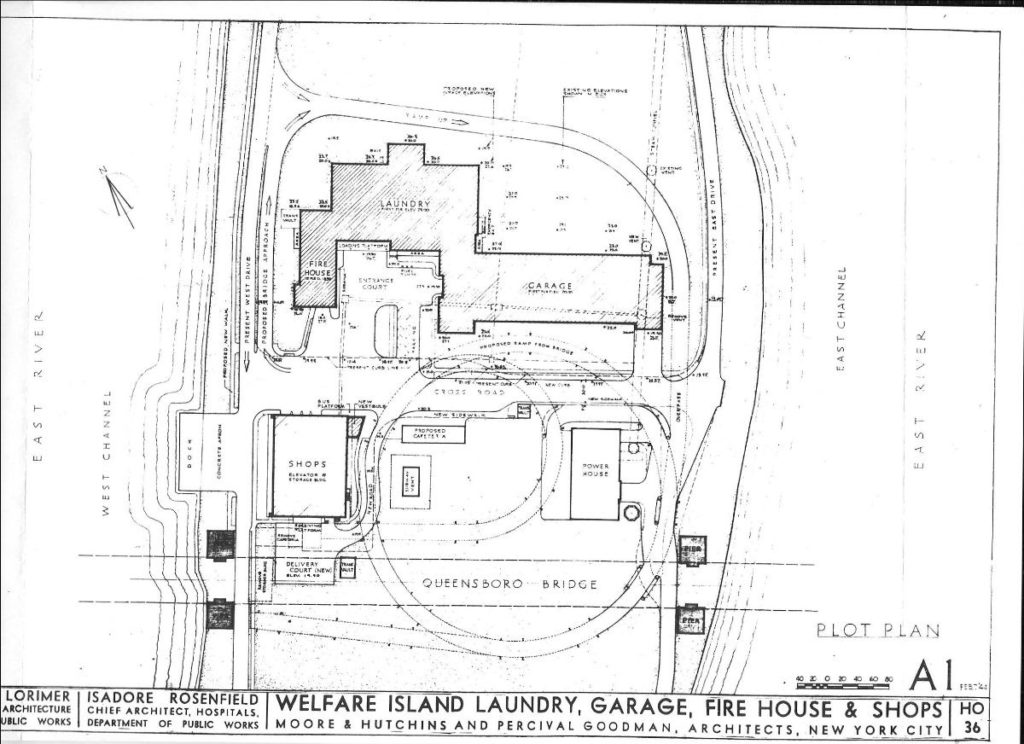

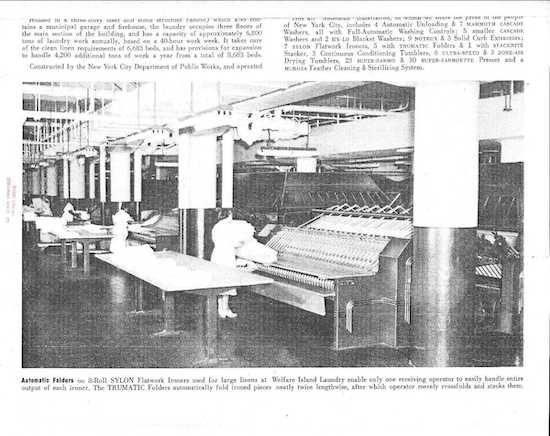

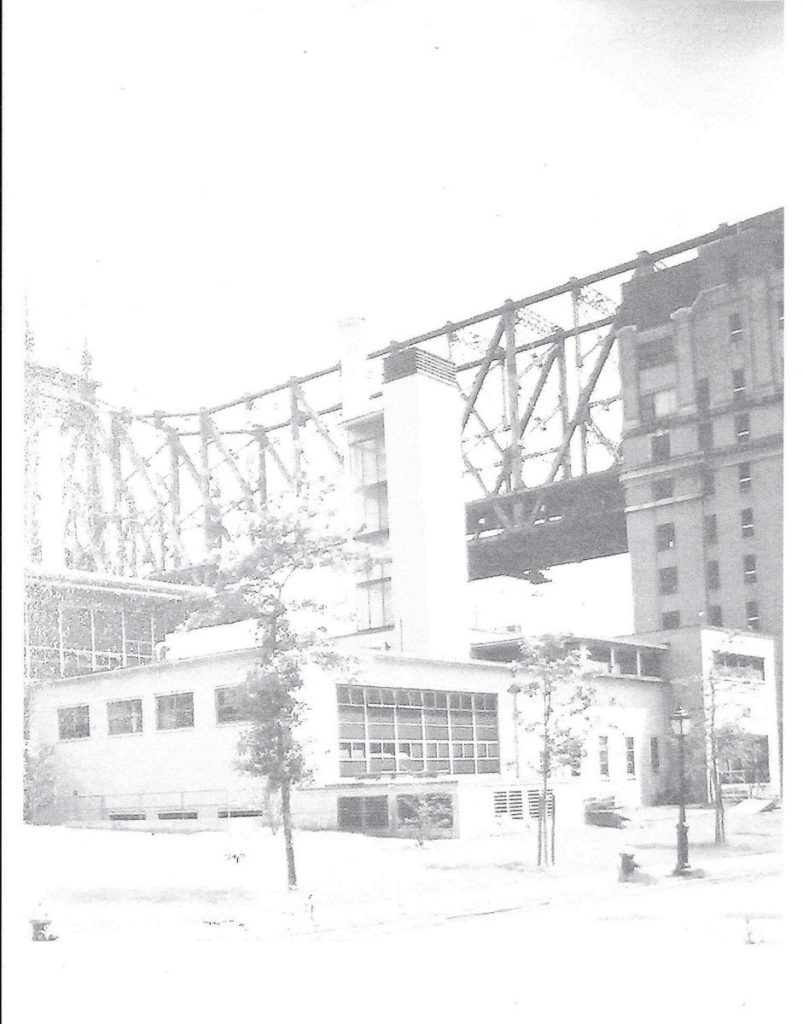

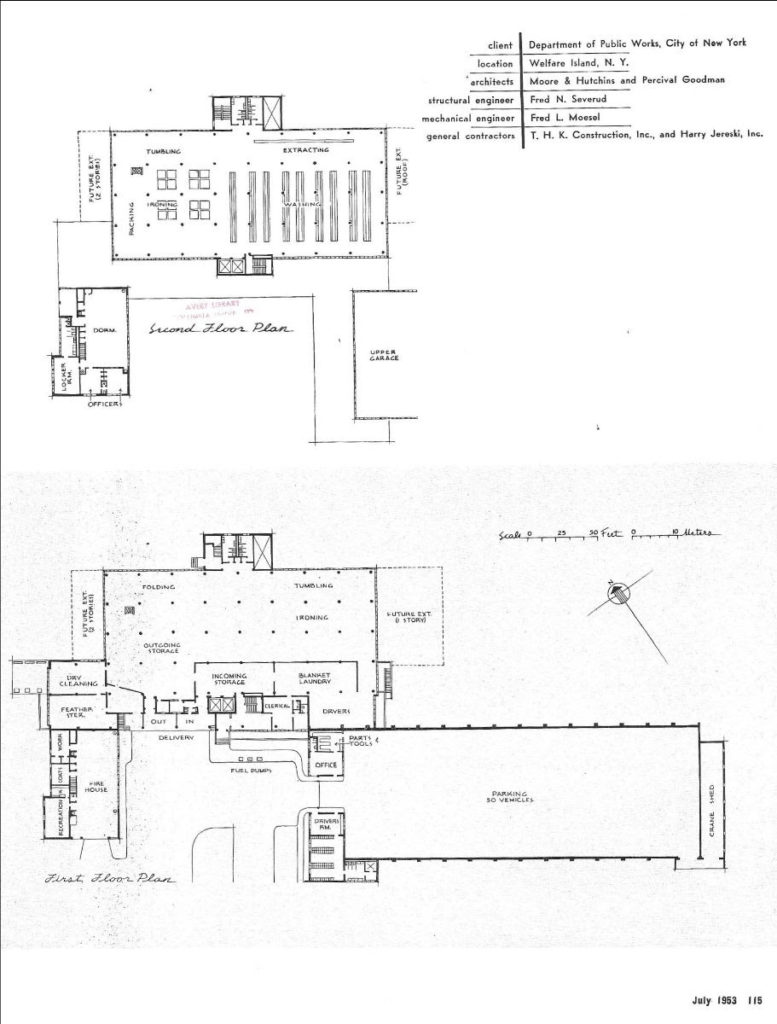

When I moved onto the island in 1977, the laundry was closed, the garage closed and only the firehouse was being used by the FDNY Mask Unit. This is a unit that would deploy canisters of supplemental air to firefighters on scene. Eventually, the Mask Unit left and it became the home of the tram office.

I always admired the building with the blue glass and the tower. It turns out the tower was for drying fire hoses. There was a terrace on the second floor overlooking the rivers.

I wondered why not entrepreneur came and made a destination restaurant there, with its light architecture and tinted blue windows. The window diffused the sunlight and gave a blue glow inside. The low slung look reminded me of mid-century and Frank Lloyd Wright architecture.

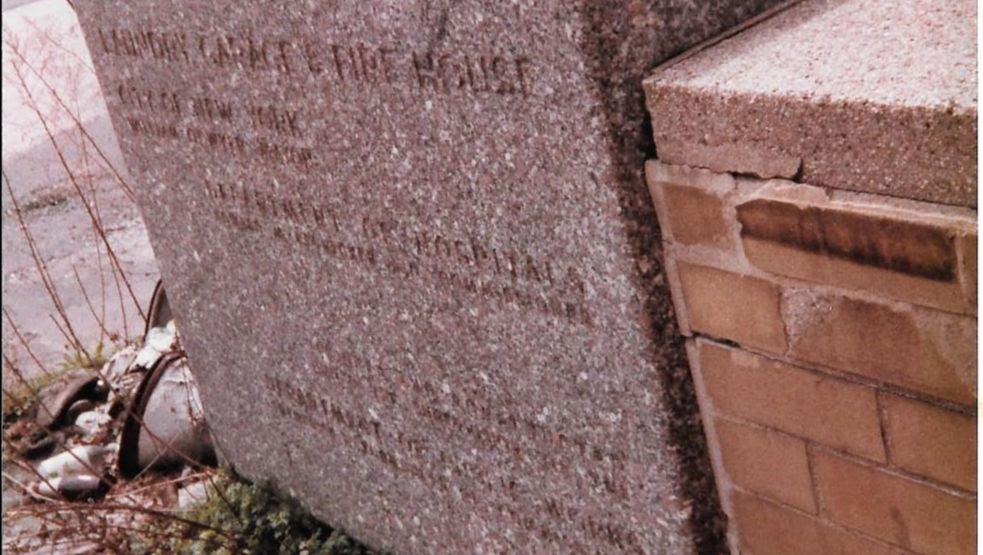

I photographed the cornerstone and wanted to see the interior. In the true spirit of the island I asked some teen age friends to show me around. It was pretty empty when I was upstairs, the laundry machinery gone. There were holes in the floors where the laundry chutes had been.

One one floor the walls were spray painted. It took many years to put together the story of Arthur Tress and his constructions from hospital furniture was what I was looking at.

A few years later I bought on E-bay the ceremonial trowel used to place the cornerstone and somewhere I located an invitation to cornerstone laying.

From the article in Wikipedia and books on Percival Goodman, I did not find any reference to this project. He did one more project on Welfare Island. It was to build over the island and call it Terrace Island. He is known for the modernist synagogues he designed in suburbs after World War II

The plans for Terrace Island and the laundry are at Avery Library at Columbia University.

Judith Berdy

Illustrations from Progressive Architecture (c)

EDITORIAL

A month of being patient, going out occasionally and doing my errands has just past. An occasional trip on a sunny day to Cornell Tech for a cup of Bloomberg Cafe coffee sit outside and admire the red bud tares.

I feel for our neighbors at Coler most of whom live in units on lock down. It sounds like eternal confinement, and many feel that way. It is difficult to be at home for such a long period but being left alone living in a 4 bedded room and worrying if you hear a cough that person may have Covid.

In order to cheer the residents and make their days better please send artwork, cards, posters, pictures of rainbows, to cheer the residents. Coler is a nursing home and you know many of the residents that you see on the island, on the bus, shopping, dining out. That is not happening now.

I am the president of the COLER AUXILIARY, a charitable organization that supports the needs of the residents. We pay for Holiday parties, entertainments, holiday gifts, clothing, special meals and all sorts of things that the hospital cannot provide. Our goal is to make life at Coler more homelike and as comfortable as possible. Your donations will bring more activities into the building and more things that can make the days go faster.

Any donation is greatly appreciated. Please make checks payable to Coler Auxiliary, 900 Main St., NY 10044. We will be glad to discuss any donation you are considering.

Judith Berdy

212 688 4836

917 744 3721

jbird134@aol.com

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries

Apr

21

Reading Eleanor’s story for the first time in years reminds me of the importance of paper archives and photographs. There is something about looking thru notebooks, binders, scrapbooks that brings the story to life.

Eleanor visited our island again in 2006. We held a reunion at the newly opened Octagon apartments. Bruce Becker, the developer was a wonderful host to the women who studied and worked in the building. I have photos of that event but they are in the RIHS office in the Octagon.

I hope you have enjoyed this series. Please send me your comments.

Judith Berdy

212-688-4836

917-744-3721

jbird134@aol.com

I look up at my bookshelf and want to acknowledge some of the reference materials and books I have used to write the 30 FROM OUR ARCHIVES articles:

This list is only published books. Our archives have over 200 binders of individual subjects from Almshouses to Zoolander. Feel free to contact us for any information you need. If we don’t have it, we can point you in the right direction to find it.

Judith Berdy

Text by Judith Berdy

Thanks to Bobbie Slonevsky for her dedication to Blackwell’s Almanac and the RIHS

Thanks to Deborah Dorff for maintaining our website

Edited by Melanie Colter and Dottie Jeffries